“He asked me what reasons, more than a mere wandering inclination, I had for leaving father’s house and my native country, where I might be well introduced, and had a prospect of raising my fortune by application and industry, with a life of ease and pleasure. He told me it was men of desperate fortunes on one hand, or of aspiring, superior fortunes on the other, who went abroad upon adventures, to rise by enterprise, and make themselves famous in undertakings of a nature out of the common road…” Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe.

Because of their dislocation, expats have made interesting protagonists for stories from the earliest beginnings of literature. Odysseus, Moses or Sinbad are just some of the characters from traditional tales that are travelling far away from the places where they were brought up.

In Western novels from the 18th century onwards, with the advent of both colonialism and the novel, the character of the expat has taken on a different slant. In these books, the protagonists are no longer primarily adventurers and explorers of strange, foreign countries. Rather, the places where these people find themselves serve as a backdrop for the development of their character, may it be a moral triumph, may it be their downfall. That´s why these books, as old as they may be, are of interest to readers who – like the many expats here – have to find a way to define their existence in an alien culture. In what follows, I would like to offer a selection of readings that should be beneficial to expats in Cambodia.

There are some canonical books expats should read if they want to understand the country where they have decided to spend some time of their life: the books on the history of Cambodia by Milton Osborne or David Chandler; Zhou Daguan´s account of life in the Angkor period; the Khmer folk tales and sayings that have been published in a number of books; the histories of the Khmer Rouge period by Ben Kiernan, Elizabeth Becker and again Chandler and Osborne. Once you are through with these, you might be interested in reading other historical accounts of life far away from home.

All the books I have chosen are from the colonial period, and they are often full of opinions on and descriptions of ‘the natives’ that today appear politically incorrect, if not downright racist. Western literature from Robinson Crusoe onwards was tightly intertwined with the colonial project and its assumption of cultural superiority of the colonisers over the colonised. For eloquent formulations of the imperialist mindset, one has to look no further than to Rudyard Kipling´s two notorious poems The White Men´s Burden and The Road to Mandalay. The hypocritical delusion of a ‘Mission civilisatrice’ – a civilising mission that the white colonisers had in their colonies and protectorates – did not only fuel French colonialism. It also underlies the works of authors who are highly respected writers until today. Nevertheless, the challenges and quandaries that the heroes of those books had to face might still be instructive for the contemporary reader. And the racism in most of these writings gives opportunity to reflect on one´s own questionable attitudes towards local people.

I have excluded travelogues such as Henri Mouhot´s Travels in Siam, Cambodia, Laos, and Annam and the many other accounts of travels in the region that publishers like White Lotus Press and Silkworm have (re-)published, because the focus of my list is accounts of how foreigners deal with their life in an alien country.

Some of these books are well-known classics that are easily available at book shops. Others are lesser known or even obscure works. As the copyright of most of these books has expired, a good number of them can be found at www.gutenberg.org or in more reader-friendly pdf format at www.manybooks.net.

1. Robinson Crusoe, by Daniel Defoe

Interestingly, the book that is often credited as the first realistic novel in the English language is the story of an involuntary expat. James Joyce has called the castaway who spends 28 years on a tropical island near Trinidad “the true prototype of the British colonist.” In a lecture on English literature he delivered in Italy, Joyce argued: “The whole Anglo-Saxon spirit is in Crusoe: the manly independence, the unconscious cruelty, the persistence, the slow yet efficient intelligence, the sexual apathy, the calculating taciturnity.” Especially his relationship with his factotum (or slave?) Friday has struck many readers as highly bigoted, and post-colonial revisions of the book have therefore focused on the Friday-character. Both the novel Vendredi by Michel Tournier and the movie Man Friday by Jack Gold turn Friday into the commendable hero of the story.

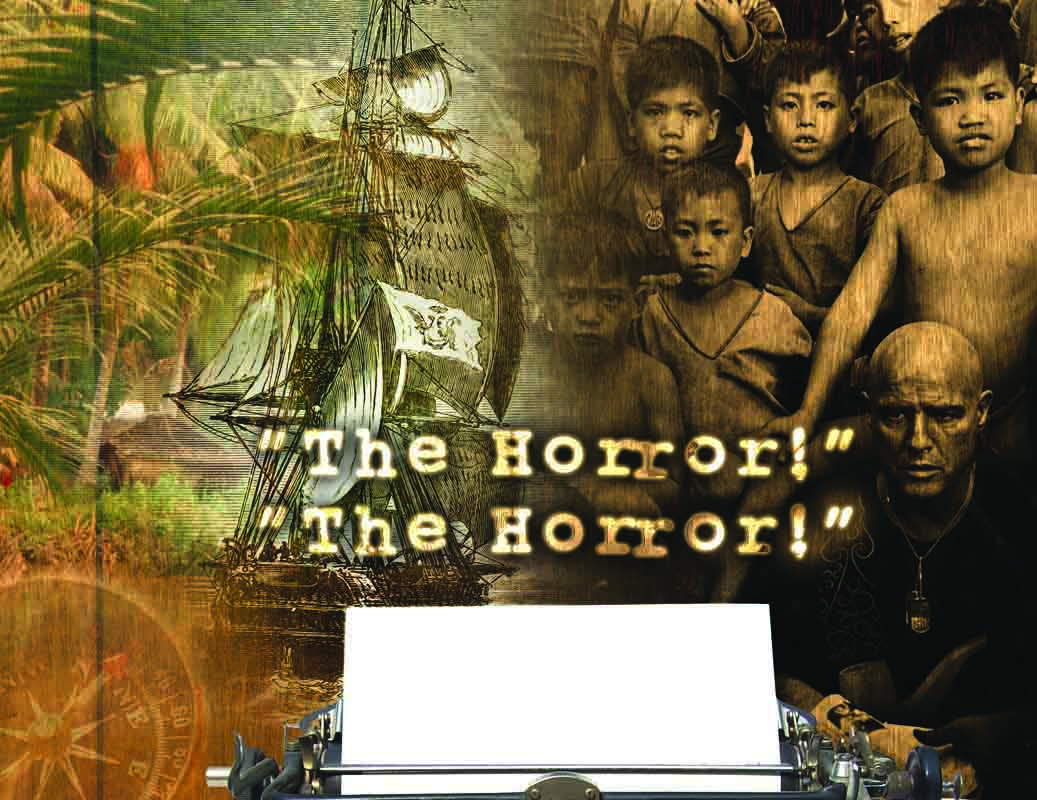

2. Heart of Darkness, by Joseph Conrad

Often touted as a ‘stark exposé of Colonialism’, this book is anything but. Joseph Conrad describes the nameless African country (supposedly the Congo) in which the story takes place is such condescending terms that Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe felt the book “dehumanises” Africans. Then again, Africa only serves as a backdrop for the personal crusade of young English captain Charles Marlow who is looking for the grandiose ivory trader Mr Kurtz, who seems to have started his own cult in the jungle. The book had a night club in Phnom Penh named after it and was the inspiration for Francis Ford Coppola´s movie Apocalypse Now (incidentally, today the name of a popular club in Saigon), which borrowed, among other things, Kurtz´ dying words: “The horror! The horror!”

Conrad returned to similar subject matters one year later in his novel Lord Jim, the story of a ‘White Raja’ in the fictional Malay state of Patusan. The film version of this story, directed by David Lean and starring Peter O´Toole, was partly shot in Angkor Wat in 1965. Disparaging remarks by O`Toole about Cambodia in an interview angered Cambodian head of state Norodom Sihanouk so much that he started to make his own films to show the world the “true” Cambodia, becoming in effect one of the first post-colonial film directors.

3. A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa, by Robert Louis Stevenson

An early dropout from Western Civilisation, Stevenson – author of beloved adventure novels such as Treasure Island and Kidnapped – bought a tract of land in Upolu, an island in Samoa, in 1890. He lived there with his family until his death in 1894. In 1892, in an attempt to set the record straight on how the US, the UK and Germany battled over control of Samoa, he published A Footnote to History. In this well-researched book, Stevenson is mostly concerned with the political machinations that led to the indigenous factions losing control over their islands to the colonial powers. At the same time, he delivers some fine descriptions of the lifestyle of the Brits, Americans and Germans who had settled in the Samoan Islands before the Samoan Civil War. His unflattering report led to the recall of two officials. One year later, he published South Sea Tales, a warm and sympathetic account of the customs and mores of some of the tribes in the South Sea that sets him positively apart from the often narrow-minded and bigoted writers of the colonial age. His story collection Island Nights’ Entertainments is also set in the South Seas.

4. Noa-Noa, by Paul Gauguin

Post-Impressionist painter Paul Gauguin must be the most beloved sex tourist and paedophile of all time. Sick of Western civilisation, he left his family in Denmark to live in the South Seas in 1891. His paintings of native beauties bathing, resting or frolicking in the sun have become fodder for endless postcards, posters, art print and calendars, and his personal relationship to these ladies has been the subject of much speculation. After a stay in Tahiti he wrote the short book Noa-Noa that supposedly describes his experiences after he had left behind “everything that is artificial and conventional”. On occasions, he leaps into prose that seems to come from the diary of a modern-day backpacker: “Between me and the sky there was nothing except the high frail roof of pandanus leaves, where the lizards have their nests. I am far, far away from the prisons that European houses are. A Maori hut does not separate man from life, from space, from the infinite…” Later in the book, he ventures into an endless treatise on the cosmology of Tahiti. Some modern scholars have argued that the book is largely a fantasy, written mostly to sell his paintings.

More saucy stuff is in his Intimate Journals, which his son published after his death. W. Somerset Maugham based his novel The Moon and Sixpence on Gauguin´s life story – which brings us to the most merciless chronicler of the life of Western colonisers in the East…

5. The Casuarina Tree, by W. Somerset Maugham

The dropout, the sexpat, the drunk, the idler – archetypical expat characters that can be found on any given night on Phnom Penh’s riverside – are all assembled in this collection of short stories that Maugham published after an extensive trip to the British colonial holdings in Asia in 1921. His account of the lifestyle of British colonial servants enraged one of them so much that she anonymously published the book Gin And Bitters to denounce Maugham’s works. Maugham added a postscript to later versions of the book to point out the fictional nature of his stories. Yet much of the material for the tales in this book and in its companion piece The Trembling Leave, set in the South Seas, came from conversations that Gerald Haxton, Maugham’s lover and secretary, had during their trips through Asia in hotels, bars and the private homes of British citizens in the colonial service (Maugham himself was apparently too shy to get people to wash their dirty laundry in public). Maugham also published the travelogues The Gentleman in the Parlour and On A Chinese Screen. His short stories are both brutal and highly entertaining.

6. Colonial Cambodia’s ‘Bad Frenchmen’: The rise of French rule and the life of Thomas Caraman, 1840-87, by Gregor Mueller

This book is not a novel, but a PhD thesis – but it’s easily as entertaining as any piece of fiction. Historian Mueller traces the life of the little-known French colon Thomas Caraman, based on documents that he found in the National Archive of Cambodia in Phnom Penh. Caraman’s many failed business ventures in Cambodia would be sufficient material for a movie. Mueller assembles a cast of characters around him that bear a striking resemblance to the many shadowy and lost types that inhabit the guest houses and bars of Phnom Penh today. Mueller had an honour bestowed upon him that only the most relevant works on Cambodia receive: his book is sold by the vendors of pirated books on the riverside alongside bootleg prints of the Lonely Planet.

7. The Royal Way, by André Malraux

It is not entirely clear what Malraux, one of the most shameless con artists in the intellectual history of the 20th century, intended with this semi-autobiographical book. But he does come across as a latter-day offspring of the down-and-out characters Gregor Mueller describes so eloquently in his book on Thomas Caraman. The narrator comes to Indochina to steal sculptures from Bantey Srey temple in Siem Reap to make a fortune, but his expedition goes horribly wrong. Malraux went to court for his attempted theft, but was never put behind bars, where he would have belonged. Instead, he became French Minister of Culture under Charles de Gaulle. Oops.

8. The Sea Wall, by Marguerite Duras

Duras’ autobiographical account of her youth in Indochina is lesser known than her novel The Lover, but it is a better book. Her mother bought a plot of land for farming from the French colonial government in 1930, only to find out that her rice fields were regularly flooded with salty sea water during the rainy season, making all attempts at cultivation useless. Her attempts to build the sea wall that gave the book its title also failed. The tragedy of her mother serves as a backdrop to her own coming-of-age story that includes an affair with a rich Chinese merchant – who might or might not have been a figment of her imagination, and who she milked again for The Lover. French-Cambodian film maker Rithy Panh did a complex movie version of the book in 2009.

9. Burmese Days, by George Orwell

Orwell’s first novel is set in in Katha, Burma, where the writer served in 1926 as a member of the Indian Imperial Police. It describes corruption and imperial bigotry in a society where, “after all, natives were natives – interesting, no doubt, but finally… an inferior people”. John Flory, the protagonist, seems to do little more than drink and to recover from his drinking orgies, and so do the other members of British colonial establishment who gather at the ‘club house’ of the small hamlet in Sagaing. Flory’s downfall is masterminded by the corrupt Burmese official U Po Kyin, who wants to join the British club. The book contains priceless description of life in Katha, but his characters border on caricatures. Well, it was Orwell’s first book, and he did describe the decadence and the waning of colonialism in the British Raj quite perceptively.

10. The Quiet American, by Graham Greene

Both deeply moving and highly receptive, this book is the fitting finale to an account of colonial literature. Thomas Fowler, a British journalist in his fifties, is an old hand in Indochina who is covering the French war in Vietnam from Saigon. The American spy Alden Pyle is a young idealist, who knows little about the country that he wants to help, but aggressively tries to do so anyway. The two compete for the same Vietnamese woman, Phuong. The book is a monument to the misled ways in which Westerners tried to help Third World countries out of their perceived dilemmas. Greene understood these dynamics so well that his book seems to foreshadow the clueless American attempt to save Vietnam from itself in a war that is internationally known as the Vietnam War, but in Vietnam itself as the American War.

After the end of this war and the other post-colonial conflicts in Asia, Latin America and Africa that followed de-colonisation, the West started to send advisors, development workers and other well-meaning folk to the countries over which they had wreaked so much havoc. These people would be well-advised to read some accounts from the colonial period to understand the historic legacy that they carry on today.

Dr Tilman Baumgärtel has been teaching journalism at the Department of Media and Communication at the Royal University of Phnom Penh for the past three years. He will cease being an expat when he returns to his native Germany in July.

WHO: The literati

WHAT: Essential reads for expats

WHERE: Local bookshops, gutenberg.org or manybooks.net

WHEN: This very minute

WHY: Feed your head, fellow traveller