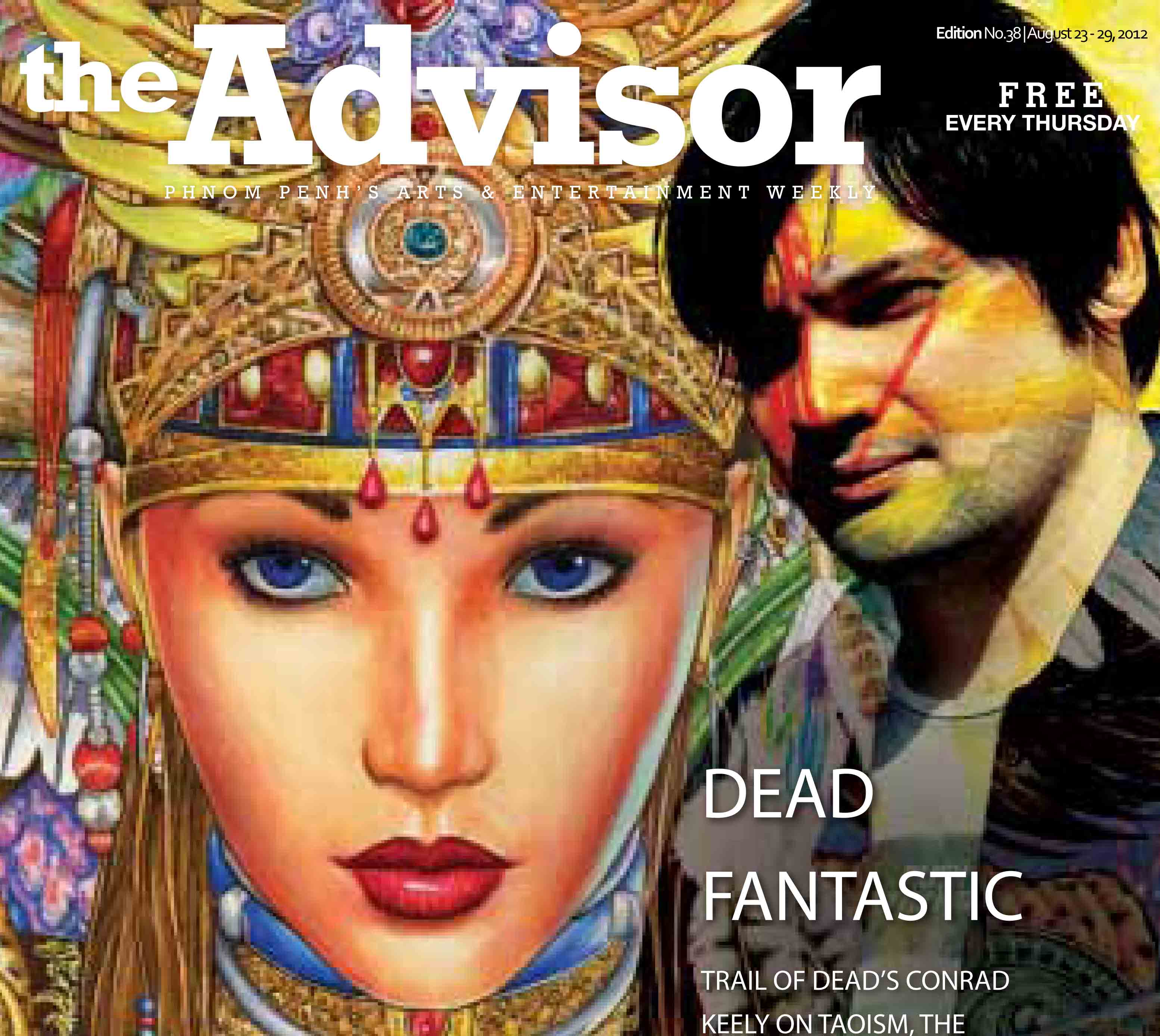

He’s the lead singer of an apocalyptic American alt-rock band famous for destroying instruments on stage, but this soft-spoken second-gen hippy is more at home in his own fantastical Tolkienesque universe – complete with languages, maps and timelines – than he is embodying the rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle. When not committing unspeakable acts of violence against guitars, drum kits and the odd piano, Conrad Keely of the ominously titled … And You Shall Know Us By The Trail Of Dead is more often to be found wearing blue ballpoint pens to a nub bringing to life the extraordinary world he’s been constructing in his mind since childhood. This half-Thai half-Englishman, born-in-Britain and raised in Hawaii, was one of the founders, along with childhood pal, drummer, vocalist and guitarist Jason Reece, of the Trail of Dead – a band once described by Rolling Stone magazine’s Andrew Dansby as a “post-punk Voltron that just might be the most exciting unit working today.” The parallel universe Keely, also an accomplished artist, has conjured forth on paper knows no borders: characters, plots, all spill over from sketches and comics straight into his music. As Trail of Dead ready for the release of their eighth album, the material for which was recorded in Germany earlier this year, Keely is working on a graphic novel here in Phnom Penh before their tour of the UK, Germany and Taiwan kicks off in October. The Advisor caught him between local gigs (“When I’m playing here, with the Kampot Playboys or Amanda Bloom and Charlie Corrie, that’s when I get to play stuff that isn’t hard rock, the stuff that I write; things like Hank Snow, Bruce Springsteen, David Bowie – things I like to sing”) to talk Taoism, the new apocalypse, and what it was like knowing Kurt Cobain.

…And You Shall Know Us By The Trail Of Dead sprang from fittingly apocalyptic roots.

My family moved to Seattle right before the big grunge explosion and it was there, at a college I ended up going to, where the Riot Girl movement started. I saw Nirvana when they were still a small, shitty band. Then I saw them as they got better and better – and then they blew up. In 1993, our lives in Olympia imploded. Not just our lives, but everyone’s lives. Things got really dark. When Kurt Cobain committed suicide, there was this real dark shadow around – everyone knew him and was friends with him. It was a really dark time. A lot of our friends got into drugs; people were dying of overdoses. Jason Reece and I had both had enough and we just said let’s get out of here. We hit on Austin, Texas because no one we knew lived there. We discovered this whole new music scene and latched onto it pretty quickly. Climate-wise it reminded me of Hawaii and even socially people were a lot more laidback and expressive. I felt really at home because people were boisterous and obnoxious in a fun way. That’s where …And You Shall Know Us By The Trail Of Dead started.

There’s a rumour about the name being inspired by a Mayan chant, but that isn’t entirely true, is it?

We’d seen this anime movie called Legend of the Overfiend. There was a scene with this army going through the land and leaving this trail of destruction and desolation, so that’s what I was thinking – the image I came up with while we were driving around coming up with names. I said: [adopts creepy nasal voice] ‘You will know us by the trail of dead.’

In that exact voice, I hope.

[Laughs] In that exact voice – and it made us laugh. I was thinking of Jason’s ex-band-mate, who’d started a band in Olympia called Behead The Prophet And The Lord Shall Live, so the idea of these long Doomsday-sounding band names was on our minds. But that was the name that made us laugh the most.

All these scriptural references: has religion played much of a part in your life?

My mum was raised Catholic, my dad was raised Muslim and my stepfather was involved in this New Age church back before they’d even coined the term ‘New Age’. They were interdenominational – they studied Hari Krishna, Buddhism, everything – and they tried to find fundamental truths in all of them. One of my favourite gospels, which I always go back to for inspiration, is the Gospel of Thomas and that’s been removed from the Bible. It was taken out as an apocryphal gospel during the Council of Nicaea. It’s fascinating: there’s no story in it, just parables, sayings. ‘Jesus said this. Jesus said that.’ In the Bible it says: ‘Give unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s; give unto God that which is God’s,’ but in the Gospel of Thomas it says: ‘Give unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s; give unto God that which is God’s; give unto me that which is mine.’ It’s a very interesting, cryptic twist. It makes you think: what is mine? That became a lyric on our last album, Tao of the Dead. I was raised thinking about spirituality over religion and my parents had a healthy distrust and disdain for organised religion, even though they believed in the idea of Christ and his teachings. So when Jason and I met, I opened him up to all these ideas and theological discussions – that teenaged questioning thing. Then when it came to the band, it was more like these ideas became symbols and themes around which to wrap concepts.

My lyrics have always been a platform for what I’m interested in and I’m genuinely fascinated by these things. We live not in an apocalyptic time, but we’re obviously leading up to something – some massive world event – that’s going to change the way global society has been moving this past 200 years since the Industrial Revolution. We’ve set this ball rolling and it’s impossible for us to stop. All of us know what’s wrong with society: there’s too many cars, there’s too many people, there’s too much pollution, we’re destroying the planet. We can say these things all we want, but the ball is rolling. Are you and I, right now, willing to give up television and the internet and electronics and move into the woods? No. None of us is going to do that. We’re a part of this snowball effect. We’re caught up in it, we’re moving along with it, and it’s just going to play itself out to its logical conclusion. To live in this time is fascinating and frightening at the same time. I address these things in our lyrics.

How much of a crossover is there between your music and your art?

There was a time at 17 or 18 when I was convinced that, because music was such a discipline for me, I couldn’t do art and I actually tried to give up. In that concerted attempt to stop, that was when it came to me that I had to do art: art was not a choice. It’s not a choice for people who have that drive. You have a pen in your hand and a piece of paper and it’s going to come out. So when I took all my stuff back from my agent and said I’m not doing art any more, it was kind of a big deal. It was a symbolic gesture: I wasn’t giving myself any other option but to do music. I think it was this raw passion that music brought out in me.

The picture that led to what I’m working on now is the cover of our sixth album, Century of Self: a boy looking at a skull in this room cluttered with things, which is basically inspired by what my mum’s house looks like. She has Buddhas and books and knick-knacks everywhere. That led to the question who is this boy and what’s he doing here? And that led to the storyline of the last album, which became the graphic novel for the comic, and then this album led to the novel I’m working on, Strange News From Another Planet.

The boy’s name is Adsel and he’s a savant who was found by this monastic sisterhood. Because he’s found to have special powers, they take him to this temple on an island and to get there, he goes onto this ship, The Festival Time, which was one of our songs and I made a graphic out of it. All of these characters are reflections of people I know, periods of my life, and based on my experiences of travelling and touring – even though it’s set in this science fiction fantasy parallel universe.

What would Sigmund Freud make of this universe you’ve created?

Freud? I don’t know. I started world-building when I was nine, shortly after I read The Hobbit for the first time. This world was something I grew up with. It became something that’s so real it’s like an alternate reality that I can go to when things here get too tedious. I did all the typical world-building things, like create languages and maps and timelines.

Art is my celebration of what I love visually, music of what I love to listen to, and writing is my celebration of the language that I love. English has such an amazing history and it’s such an unlikely success story. Patrick O’Brian, author of the Aubrey-Maturin ‘Master and Commander’ series, is definitely one of the masters of the English language and has been a sort of style guide for me. He breaks all the rules.

Are you breaking any rules with Trail of Dead?

In some ways we’re embracing old rules. I believe in the Western music tradition: I love JS Bach and Mozart. A lot of the rules we apply to our music are actually classical things. On this new album, I was really into the idea of musical motifs and there’s this one ascending riff that’s used in four or five different songs deliberately, this running motif that you hear through the album. There’s a few of those, just to create a sense that the album is one work, one piece – a mini symphony. In that sense, I like the old rules that got forgotten about in rock. Rock broke down so many walls. A lot of the kids that were raised with rock didn’t bother to learn those rules, but the pioneers of rock did. You’ve heard of Peaches? We’ve done a tour with her and she’s hilarious; awesome lady. She recently did the Jesus Christ Superstar musical. They did a show in Brooklyn, New York and it was just insane – and it pissed me off because I’d been wanting to do a Jesus Christ Superstar thing for so long. The opera tradition hasn’t died. People don’t necessarily call it opera any more, but the idea of music as narrative and music as high drama still exists.

There’s no shortage of high drama in the new album, if what you just played for me is anything to go by.

People who are familiar with our band and hear this album will say this is the most aggressive Trail of Dead record in a while. A lot of the aggression that I put into music is addressed to other kinds of music.

Hence the lyrics to Worlds Apart: ‘Look at these cunts on MTV / With their cars and cribs and rings and shit / Is that what being a celebrity means? / Look boys and girls here’s BBC / See corpses, rapes and amputees / What do you think now of the American Dream?’

Things that have always irritated me with music are the lack of convictions, an approach to music that doesn’t display great passion. Passion is what music inspired in me and something that I wanted to convey through music. When I saw Bikini Kill playing on stage – I’d see these local bands which are now legendary in reputation – this raw emotion and energy, inspiration, it was almost uncontrollable. I didn’t know what to do with it. It wasn’t the exact same thing I’d feel when I looked at a Warhol painting, you know? Looking at a Monet, I just didn’t feel like jumping up and down. There’s that visceral thing that music can do to you, especially when you’re at that age when your hormones are raging. It’s so physical, the effect of music. I’ve read a couple of books on the psychology of it and I know there’s something special about how vibrations work on the body. That’s what makes music have this ability, this capacity, to change the way people think, and spur these movements. It’s very powerful: it changes chemicals in the brain; it creates endorphins and does all these really weird things. I didn’t know that at the time, when I was young, but I knew that music created the most powerful passion in me.

WHO: Musical prophets

WHAT: Conrad Keely and friends

WHERE: Equinox, St. 278 (Aug 25), and The Willow, St. 21 (Aug 31)

WHEN: 9pm August 25 and 31

WHY: The beginning is nigh