‘Master of Suspense’ Alfred Hitchcock famously noted that “Mystery is an intellectual process… but suspense is essentially an emotional process.” Phnom Penh Noir tackles both as it steers us through the seamy underbelly of a city that is seemingly all underbelly.

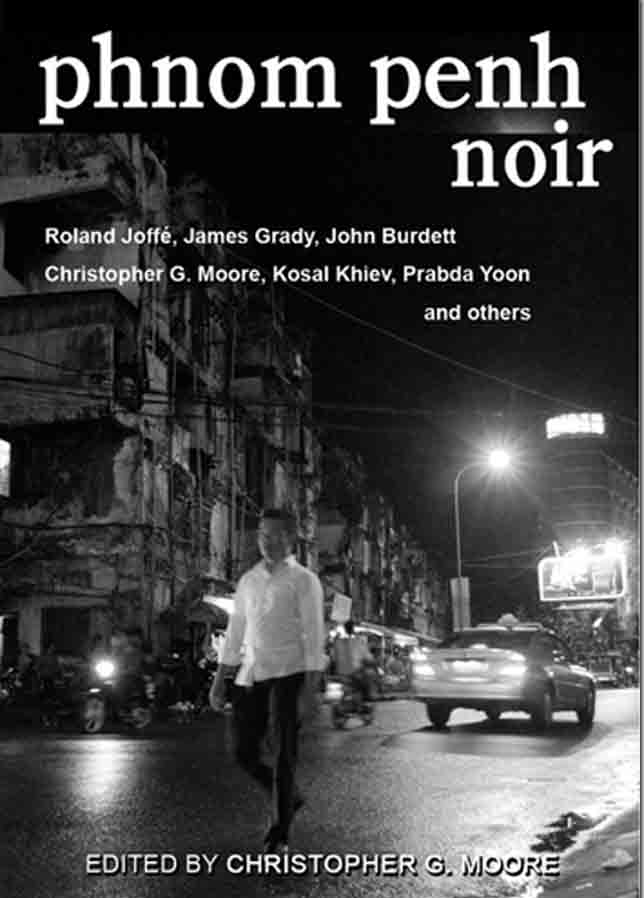

Noir, as a genre, cops an attitude of cynical detachment, a jaded worldview and an obsession with crime. All of these are things easily found among the flotsam and jetsam of foreigners who pass through Cambodia’s capital. With this and the city’s troubled recent past in mind, Southeast Asian publishing house Heaven Lake Press put together a compilation of Noir crime stories set locally.

The two worst things a book can do are make readers perform so many mental gymnastics that they find it more difficult than rewarding, and make readers lose brain cells with its vapidity. Phnom Penh Noir occupies a satisfying middle ground: thrilling crime tales are peppered with hard-won insights into local culture and history.

The book is made up of 14 stories as diverse in length as they are in subject matter. Love and Death at Angkor follows a young man taken in by a cult who practices Hindu sex magic in Bantaey Srey temple; if David Foster Wallace’s work ‘makes the head throb heart-like’, this makes the sacral chakra buzz brain-like. Meanwhile, Andrew Nette’s Khmer Riche deals with “[t]he classic bandit capitalist that half of Asia’s wealth was founded on” in a gripping tale that shines a flashlight into a world few of us will ever set foot in.

But the most horrifying tale is Hell in the City by young Khmer author Suong Mak. It isn’t horrific in a b-horror-movie-shock-value kind of way, but more in a what-I’m-talking-about-here-is-completely-serious-and-I-need-you-to-feel-every-second-of-it kind of way. Rightly so, dealing as it does with sexual violence in Khmer culture.

Setting itself apart by not taking place in the present day is Richard Rubenstein’s Sabbatical Term. It follows a Western journalist who’s one of the few foreigners allowed access to the Khmer Rouge regime. His falling in love with a top level official as well as the regime’s Communist ideology leaves him blind to the horror unfolding around him until it’s almost too late.

What the stories suffer from most is a sort of forced psychological machismo (only one contributor is female) which makes it hard to take seriously. Only a few of the authors are guilty of this but when they screw this up, they reinforce the absolute worst of the ‘Southeast Asia playground’ mentality. Take for example this sentence from Fires of Forever: “Not the sunburned tourists getting on that allegedly air-conditioned bus to go sightseeing at the pile of skulls in the Killing Fields for an inoculation of ignoble history that lets them justify their trip here and the coming night in bars where blowjobs from smooth-skinned black-haired beauties are always only a few dollars more.”

Some of the insights that pepper the stories feel like things creepy bar flies will tell you unsolicited. In Rebirth, author Neil Wilford speaks of “the walk of shame in the harsh morning light” and how whores “never look the same then, especially at the ATM”.

In spite of occasional cringe-inducing outbursts, Phnom Penh Noir is a worthwhile read that entertains and enlightens as it takes you through the many facets of a city you thought you knew so well. If you’re not careful, you just might learn something – even if that something is that Phnom Penh really is all seamy underbelly.

Phnom Penh Noir, edited by Christopher G Moore, is available at Monument Books on Norodom Boulevard for $16 and at

phnompenhnoir.com.