Even the most loquacious fighters turn pensive in the dwindling hours before a contest. They stare vacantly into the distance. Wrap their hands. Shadow box. As hyperfocus sets in, ambient chatter is quieted by the sound of a boxer’s heart, the roar of screaming fans silenced by the instinct to survive.

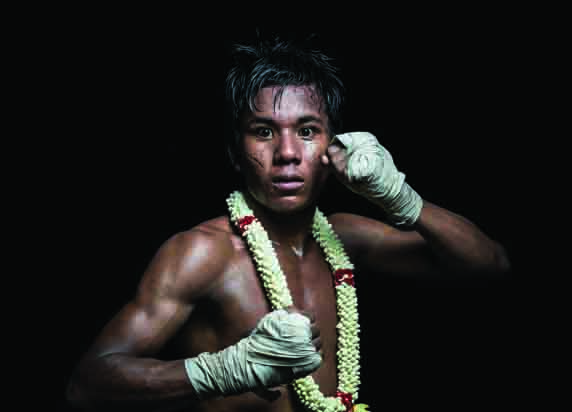

In Khmer Boxers, a series of portraits on exhibit at the French Cultural Centre, Antoine Raab attempts to capture that tense, almost meditative state that fighters attain during combat. The challenge, Raab says, was to photograph boxers while “they are still in the mood of the fight”.

After some experimentation, Raab set up a portable studio next to the ring and photographed boxers in the minutes immediately after a bout. He used a black backdrop to hide the ringside cacophony of fans, coaches and corner men. “I wanted to focus on the fighter, not the fight.”

Raab captured young fighters and old, the famous and the unknown. The portraits that emerged were greatly influenced by the five rounds that preceded the shutter snap.

In the faces of older veterans – Sao Bunoeun, Nuon Sorya – we see the unshakable confidence of experience and age. Sao Bunoeun poses with his heavily wrapped hands down at his waistline, elbows back, chin stuck forward, like a shirtless soldier standing to attention. Beads of sweat glisten against his dark torso. Nuon Sorya, the ‘Old Tiger’, stands expressionless, hands akimbo, wholly unfazed by fights or photos.

Many fighters seem older in Raab’s portraits – the boyish smiles of Sen Rady and Kim Dima are replaced with mature and menacing stares; Pao Phuoek and Chey Vannak, their spirits flagging, appear aged with exhaustion and the scars of previous battles. And then there are the kids, the under 14s; their skinny, under-developed frames supporting expressions far older than their years. “It’s not like football,” Raab says. It’s most certainly not.

A Paris native, Raab began photographing boxing three years ago, but he couldn’t decide on the best way to approach his subjects. “The strength of the fighters attracted me,” he says. “I wanted to show that.” The concept finally came to him while standing ringside at a Nuon Sorya fight.

Between rounds, Sorya, who Raab had encountered previously in France, stood staring at the crowds below. Their eyes met. “I could see that he saw me, but he didn’t see me,” Raab says. “It’s like he was floating.” Upon discovering that altered state of consciousness commonly referred to as ‘battle trance’, Raab set about trying to capture it on film.

The result, however, is far from an unflattering collection of blood-thirsty brutes. In some sort of delicious paradox, Raab’s pursuit of the warrior’s savage essence captures not only their strengths, but also their frailties. And, at last, we understand why, in the dwindling hours before a fight, they go quiet.

WHO: Antoine Raab

WHAT: Kun Khmer fighters

WHERE: French Cultural Centre, St. 184

WHEN: March 7

WHY: Far from an unflattering collection of blood-thirsty brutes