“We didn’t like the name rock steady, so I tried a different version of ‘Fat Man’. It changed the beat again, it used the organ to creep. Bunny Lee, the producer, liked that. He created the sound with the organ and the rhythm guitar. It sounded like ‘reggae, reggae’ and that name just took off. Bunny Lee started using the word and soon all the musicians were saying ‘reggae, reggae, reggae’.” – Derrick Morgan

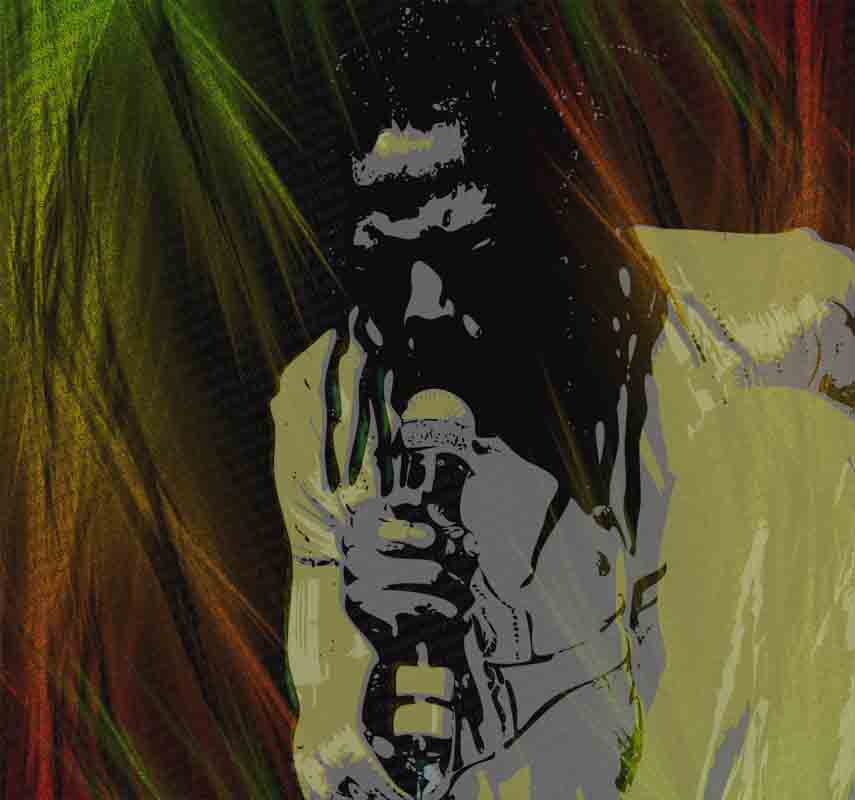

It would take Eric Clapton’s 1974 cover of I Shot The Sheriff to bring the music of Bob Marley – the dreads-sporting spawn of 1960s’ Jamaican ska and rock steady – to the rockers of the wider world, but when reggae finally made land, it made land in style. By 1972, this new rhythm had bubbled to the top of the US Billboard Hot 100, first with Three Dog Night’s roots cover of Black And White then with the gentle contemporary groove of I Can See Clearly Now, by Johnny Nash. From the loins of pioneers such as Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and King Tubby have sprung forth a new generation of lyrical Rastafarians who, like their forefathers, use the sacrament of music to promote everything from ganja to the unifying concept of One Love. Led by expats, such a culture is taking root here in Phnom Penh: on January 25, a new collective of believers will unite under the moniker Wat A Gwaan (Jamaican patois for ‘What’s going on?’ – see our cheat sheet for more) for a night of worshipping at the Jamaican altar. The Advisor meets the creative force behind Cambodia’s first reggae sound system festival, Kaztet D (MC, singer, activist, made in France), to talk Shiva, music as activism and how to fake it in Rastafarian.

What is it about reggae in particular that ignites your artistic passions?

I’ve always been an activist in music; I try to unify the people through projects. After I had some experience, I wanted to share it with younger people so I built a collective and a studio in France. I come from a family who travels a lot: during the ’90s, when I was a teenager, I started coming to Asia. I started to write music and sing when I was living in Vietnam in ’96-’97, when I was 15. My father was an adventurer: doing his own thing, architecture. I also come from a background in architecture. I went back to France when I was 17; that was tough. I put all my energy into music. I went to Paris for a while and met some musicians who were older than me and soon I was the rookie of the band. They taught me a lot: we were rehearsing three times a week, doing a lot of concerts in Paris. I started with hip hop then moved into reggae: hip hop and reggae are always the two sides, very related. Hip hop comes from reggae music. I come from the generation that started to listen to hip hop at the beginning in the early ’90s in France, when we had the first hip hop hits on the radio.

Why is reggae taking such a convincing hold in Southeast Asia?

The first reason is that reggae music comes from Jamaica, a southern country with a tropical climate. It’s also quite a poor country. In the southern countries, there are some things that are common: between Africa, Asia, South America, the Caribbean. Going back to the old story there are a lot of similarities between reggae and Asia, specifically Jamaican culture. The history of Jamaica, like all the Caribbean, was one of slavery for a long time. On the islands, very early on, there were people fighting against slavery: the Maroons. They were rebels. At the end of the 19th century and early in the 20th century, before the real Rastafarian movement, the descendants of slaves still had relations with Africa. Jamaica has the strongest links to Africa: in the music, percussively, in the culture. Then the Indians came, bringing with them Hinduism. Even now in India you have some saddhus (‘holy men’) with dreadlocks, exactly like Rastafarians. This has been Indian culture for thousands of years: in Hinduism, Shiva has dreadlocks, Shiva smokes ganja, Shiva is related to fire, considered a holy thing.

I had no idea Shiva was a stoner.

Absolutely! He’s the Lord of Bongs! In every Shiva festival in India, alcohol and meat are forbidden but it’s OK to smoke ganja because it opens the third eye. Indians brought this spiritual relation to the holy plant. Here in Cambodia, Hinduism was overlaid on animism and became Theravada Buddhism. Cambodia is probably the most Indian culture in Southeast Asia.

How do you differentiate between hip hop and reggae?

Hip hop is something that, everywhere in the world, has become very commercial – much more than reggae music. Reggae music is something people all over the world try: people playing; reggae bands, even jazz covers of Bob Marley, but that’s still something. Today you have hip hop in all the biggest clubs and just a little bit of reggae: it’s a very different situation. What’s interesting in Cambodia is we have more musicians, bands and artists in reggae than in most other countries – apart from Thailand, where there’s a big reggae scene. But in Thailand and, to a lesser extent Vietnam, it’s mostly DJs and producers, not bands. There, it’s more ‘turntable reggae’, the sound system culture.

Does reggae in Southeast Asia still serve a role as social commentary?

Absolutely! Reggae music is engaged music. Here, reggae music matches quite well with Khmer music. Dub Addiction know this. The groove is the same, that’s why at the beginning it was easy for DJ Khla to sing over reggae music with Dub Addiction even though he didn’t know anything about it. There’s some musical similarity. If you hear some old Khmer psyche rock, some songs sound like slow ska music, which is very close to reggae. The effects they were using here at the time and the effects they were using in Jamaica were very similar; you had the same influences – like some of the songs by Ros Sereysothea and Sinn Sisamouth; most of the famous Khmer psychedelic artists.

Now there’s a revival of all this and many bands are working in this direction, including a lot of young Khmer bands, like The Underdogs and Kok Thlok, but they play with more traditional Cambodian instruments. Then you have expat bands producing original reggae: Dub Addiction, Vibratone and Jahzad. Dub Addiction are getting quite big, which is very nice and they’re working on a new album with only Khmer artists because they want to bring more Cambodian people into reggae music and the way to do that is to touch them with their own language. Vibratone is interesting because their bassist Ben, the guy who runs the Reggae Bar, has been producing reggae for a long time and Maia is a very good singer, even though she doesn’t come from reggae music; an amazing person. Something is definitely happening with Vibratone and it’s very interesting.

If reggae evolves in Asia, I hope it evolves into more social commentary – a challenge to the status quo. In Europe, reggae music isn’t very engaged; most of the time it’s very light and quite commercial. Also, because the economy is so bad in Europe, it’s very hard for the people who are working in an engaged way, especially in France, where people are very divided. Reggae music doesn’t take part in most of the debates; they do only light reggae music, about ganja and women, but there’s so much more to it than that and DJ Khla was a good example. He’s a Khmer guy who doesn’t come from reggae at all, but he was doing some songs that were very close to reggae music.

DJ Khla was recently forced to leave the country because he switched from publicly supporting the government, as an artist, to supporting the opposition.

He met the guys from Dub Addiction and they started to make some songs together. He’s an amazing singer: the voice, the rhythm, the lyrics. And that’s the problem: the lyrics. For a very long time he was on the government’s side, but then he changed to the opposition’s side. Everybody knows he cannot come back to this country and I can’t talk too much about it. I know he’s in France and I think he’s OK, but still he has family here… He sings in Khmer, so Cambodian people understand the lyrics straight away. He was once related to the army, singing propaganda for them, then he met Dub Addiction and things started changing in this country. He made a track where he sings the rules of the opposition party. If you sing this in Cambodia then you’re out; you cannot stay here. If you are European you can just leave and it’s OK because this isn’t your country, but if you’re Khmer you can’t.

Is this the start of a more political direction for new music in this country?

That’s a very good question. At this time? I don’t know. Probably, if you look at what’s happening on the streets. If it’s happening on the streets, it’s happening in art also. The other problem is that fighting against something is quite easy, but what are you fighting for? Everywhere in the world, it’s the same problem: this attitude where they think they can go anywhere in the world and tell people how to do things. ‘You should do this for human rights.’ This is the problem for engaged people everywhere.

What can we expect at Wat A Gwaan?

It will be a reggae music sound system. We’ll have most of the people who play reggae music – producers, DJs – in Cambodia now, because all the activists who’ve come from different places in the world are here in Phnom Penh.

Including Cambodians?

Not yet, but we’re waiting for them! Unfortunately DJ Khla isn’t in the country any more so we can’t ask him to come as MC. From what I know there is still no Cambodian reggae DJ or MC here and that’s why Dub Addiction is doing this new album with Cambodian artists. We’re also very open to any collaboration, any style.

We want all the people who play reggae here to bring their energy together. It’s a mixture of engagement, spirituality and fun. As an MC it’s about flow, it’s about playing with words, talking about funny things. Sometimes I have to work on my set so that it’s not too engaged! The biggest influence for me over the past three years has been not the gangster stuff, but grime music from London. Grime is where you have some MCs coming from hip hop and some MCs coming from ragamuffin, ragajungle, dancehall: the Jamaican part of it. It’s a basic beat, two step, with a lot of bass and very fast time. You just grab the mic and… [Growls] This is more like punk. The flow is very sharp, very precise. Some of the MCs are very smart and have very intelligent lyrics.

Today, you have two schools of sound system: you have the UK school, which is more dub and roots, and you have the Jamaican school, which plays more new productions and dancehall. The two types of music are connected but very different.

In Wat A Gwaan, we want to promote all reggae music and we especially want to promote reggae music coming from here and to put our energy into this – to plant the seed. Cambodia is one of the easiest places in Asia to do this. I can hardly imagine living anywhere else!

Tell us about your line-up.

Polak is a producer and DJ from Hungary. He’s produced drum ‘n’ bass and hip hop and he raps also. Sometimes he’s a bit shy on stage, but we’re working on this! [Laughs] He’s got real stage presence, though. He’ll be using keyboards and sound production and all sorts of other effects. He will be mainly playing UK dub stepper; he lived in London for a while. It’s what we hear in Europe a lot now. Dub Addiction play a lot of stepper.

Then we have Tonle Dub and Mercy. Mercy’s from Africa and she knows all about African music. She knows what reggae is talking about more than anyone else here! Tonle Dub is German, a very nice guy. He probably has the best music knowledge – in any style – of anyone here in Phnom Penh. He’s a real music library, especially with reggae music. The scene in Germany is really something!

And we have Professor Kinski, who is probably the biggest producer in Cambodia. He’s been doing reggae music for a long time with local artists, but he also does punk music, hip hop, electronic music, amazing remixes of the Cambodian Space Project. A lot of different things! He’s also a very, very good MC. He’ll be playing his own stuff plus some productions made of reggae; dub; a bit of Khmer music; electronic music; Khmer samples and vocals. This is going to be big. I’m really waiting for this – he’s amazing! He’s the Mad Professor of Cambodia: effects, reverbs, delays…

We have me also. I don’t know yet whether I’m going to mix a little bit or only be MCing or singing, but maybe I’ll be selecting a bit at the beginning – I’m more of an MC, a reggae selecta, than a DJ. Do I sound more French than Jamaican? Kind of mixed, I think. You will see!

Chass Sound is a new sound system from Siem Reap. DJ D’Tone has already played in Phnom Penh. He’s been fascinated by reggae music for a long time and he’s a purist. Normally he plays vinyl, old school. His team are mostly from Brittany, so not exactly French – they have a different language and culture, which is interesting. I love this region. These guys will be representing on the one side Siem Reap, which is where they all live, and on the other side Brittany: DJ Nicko, DJ Mat, RDrum and MC Chase. It will go from reggae and soul to perhaps jungle and a bit of drum ‘n’ bass, but mainly reggae music, of course.

WHO: Wat A Gwaan

WHAT: Reggae sound system festival

WHERE: Slur Bar, Street 172 & 51

WHEN: 9:30pm January 25

WHY: Ah sey one (‘It’s great!’)!