Thierry Cruvellier, author of Master of Confessions: The Making Of

A Khmer Rouge Torturer, examines an engima

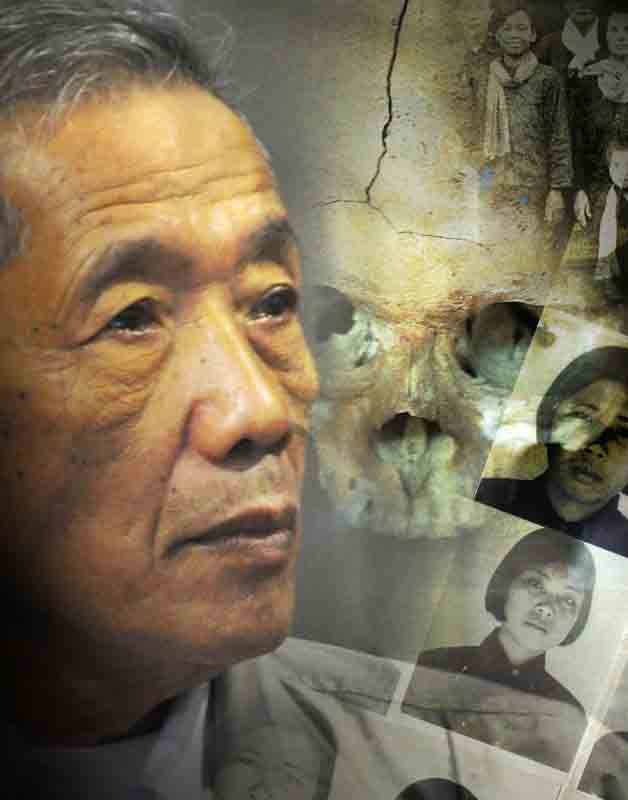

He was born in 1942 in the small rural village of Choyaot, in the populous rice belt province of Kampong Thom, where his parents gave him the name Kaing Guek Eav. In his teenage years he was considered a model student, excelling at mathematics. Surviving photographs of the teenage Kaing show an attentive, even attractive, youth. A high hairline, raised eyebrows, the hint the person staring out at you might be a tad serious, but nonetheless a face that beams with hope and possibility.

Contrast this image with the thousands of photographs discovered in the files of S-21 (Tuol Sleng), the former interrogation centre and ‘ground zero’ for the horrors committed by the Khmer Rouge. Here, captured human faces leave us with a starkly different impression. Haunted, exhausted, confused, bewildered, they stare out in black and white with expressions of evaporating hope.

In 2012 Kaing Guek Eav, or ‘Duch’ as he was known by his fellow revolutionaries, was convicted by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) for crimes against humanity, murder and torture committed while director of S-21. Duch had admitted his guilt prior to the trial, stating several times that like an “elephant carcass” he could not hide his past “under a rice basket”. As such, his trial was a matter of determining what he was guilty of and the form of his sentence.

The journey that brought Duch to this point is an extraordinary one and a story central to the new edition of Thierry Cruvellier’s 2011 book, Master of Confessions: The Making of a Khmer Rouge Torturer. A seasoned journalist whose reportage has taken him to international criminal courts in Rwanda, Sierra-Leone and the former republics of Yugoslavia, Cruvellier is an ideal guide along this long and complicated path.

Eloquently written, artful and insightful – sometimes even amusing – Cruvellier’s volume does a persuasive job of bringing the many threads of Duch’s past, his trial and the tales of countless others (victims, survivors, colleagues, expert witnesses, legal counsels) together, keeping the reader mesmerised. The result is a book that reads like a novel, but never compromises the memories of the people captured between its pages.

Underpinning it is the captivating question: how did this man, a star pupil, transform into Duch, the Khmer Rouge pariah? Furthermore, we’re challenged to consider whether such a definition is overly simplistic given the events, personalities and politics that dissect his story. Significantly, Cruvellier also identifies other opportunities rendered by the retracing of Duch’s journey. This includes the capacity, drawing on evidence from the trial’s testimonies and victim statements, to drill deep into unanswered questions about the Khmer Rouge. More subtly, the author compels the reader to think about what Duch’s case means in terms ‘justice’ and, less comfortably, what his actions reveal about the human capacity to commit unspeakable acts.

I caught-up with Thierry, a native of France but currently completing a book tour in the US, to ask him about the arguments, ideas and themes raised by Master. Starting with the most obvious question, what drew him to Duch’s trial in the first place? “I had been covering war crimes trials since1997 when in 2007 I was asked to come to Phnom Penh to help train Cambodian – or Cambodia-based – journalists to cover the upcoming Khmer Rouge trials. I realised then that the Duch trial was going to be a unique opportunity to get the voice of the perpetrator, due to the fact that, firstly, Duch was essentially pleading guilty.

“Secondly, the civil law system that applied before the ECCC allowed a full trial, as opposed to other international tribunals where guilty pleas result in an agreement between the prosecutor and the accused, ending up in a one-day public hearing. This made me decide to stay and cover this trial in particular.”

Reading Master of Confessions, it struck me there was no one, single Duch. I wrote down some of the words that sprung up to describe him: bureaucrat, remorseful, impassive, emotional, survivor, pragmatic, denier, scapegoat, reverent, heartless, maleficent, even ‘victim’. When the author thinks about the Duch he saw, what were the words that described him best?

“I have never thought about putting all these words together. What strikes me is how much it shows how complex and rich his personality is, which is what made the trial so extraordinary and eventful. His multi-faceted personality offered an unusual entry into the process through which one can become Duch and into how one lives with it once the criminal period of one’s life is over.

“Because he spoke so much and tried to explain himself or the situations he was in, he was probably less of an enigma at the end of the trial, but there are always aspects of him and of his choices that only he knows. What’s interesting is to consider all aspects of his personality and accept that he may have changed from time to time, but if I try to answer your question more simply, perhaps ‘believer’ comes to my mind, and ‘survivor’ in a sense that he has a very strong sense of survival.”

In another time and place, it strikes me that Duch would have made a great Wal-Mart manager, which raises the question: does Cruvellier think he was a strictly a product of the context he found himself in or was there an element of free will to his actions? “It’s hard to give a one-sided answer. In the book there is a clear reminder, from the psychologist expert I think, that Duch was not born a mass murderer. These crimes are political by essence and they are the product of particular historical circumstances in which those who commit the crimes are caught or participate in, or both.

“Yes, Duch is the product of a particular place at a particular time in history. And yes, in other circumstances, he would have been a great educationist perhaps. He was, by all accounts, a good and devoted teacher who believed in education. I smiled at the idea of imagining him as a Wal-Mart manager, but to be honest I don’t think that’s what he would have been; he was always interested in ideas.

“The element of free will is more complicated. At some point Craig Etcheson said: ‘We always have a choice.’ And Roux (defense co-lawyer) was exasperated. I think I was, too. It’s so easy to say, isn’t it? If you keep in mind – if one can ever really imagine it – the level of terror in which people had to make choices after 1975, I would refrain from judging what element of free will there would be for the vast majority of us. Free will meant death in this case.

“There was, of course, an element of free will for Duch up to a point; up until he takes responsibility for M-13. After that it gets more confusing. The whole system of thought, the ideology, the training is meant to kill free will. I guess one can say there always is an element of it that remains, but in the specific context of Democratic Kampuchea between 1975 and 1979, it is very hard to know how that surviving element would come out in each of us, or be silenced by much greater forces.”

Did the trial and other research provide any answers about why the revolution literally ‘ate its own children’? “You’re right to call it a vexing question. One thing we may observe, though, is that many revolutions have done so, including the Bolshevik and, most importantly, the original model of revolution for the Khmer Rouge: the French one. Again, the Khmer Rouge hasn’t invented something really new, but seems to have brought it to an even more radical level.

“Does this radicality, disconcerting and overwhelming as it may be, give this revolution a different nature? I don’t think so. I think the elimination, to borrow Rithy Panh’s word (the title of a 2013 book based on Panh’s interviews with Duch), is part of the revolutionary temptation and can be its ultimate result when it reduces the world to a fight between two forces, one representing mankind and the other the enemies of mankind. And when it has to justify its own dramatic failures and lies through the existence of the enemy from within, the elimination has no end. But that’s how far I can go in dealing with the ‘Why’.”

One of the more unsettling accounts in Master is the testimony of Mam Nai, a former interrogator at S-21. In his statements, he emerges as an ‘unreconstructed communist’ who you feel, given the chance, would do it all again. “I believe that there were good people at S-21 and that wrongdoing took place there, but from what I saw there were fewer good people than bad. I have regrets for that small group of good people… I have never regretted the deaths of bad people.”

What of Cruvellier’s own impressions of Mam Nai; was he really as unforgiving as he appears in Master? “Mam Nai’s appearance in court was certainly one of the most memorable moments in the trial. There was an exhibition at the Bophana Centre where Cambodians had been asked to write their memories of the trial. It was striking how many of them referred to Mam Nai’s testimony. Yes, Mam Nai appeared as the unreformed die-hard Communist, an intellectual who had worked so much at becoming the perfect party member that he never would question his revolutionary beliefs and the crimes committed in the name of them until he dies.

“He was the glacial living reminder of the intransigence of Khmer Rouge cadres, especially the educated ones. He was also a disturbing illustration of the selectivity of international justice: Mam Nai, one of the chief interrogators at M-13 and S-21, unrepentant and lying despite all the concrete evidence against him, would leave the courtroom free and undisturbed. And yet his appearance at trial would also prove to be the only moment in his life when he came as close as it gets to an expression of remorse.”

The question of ‘justice’ seems central to what we could desire from Duch’s trial. Did Duch’s eventual sentence represent justice? “If we focus on Duch’s trial, yes, of course, there was a measure of justice: he has been tried, rather fairly; the trial judgment reflected in many ways what was said and learned in court, as opposed to the appeals judgment, which seems to erase all the nuances of the case; he was punished for crimes he had clearly committed. That’s the basic measure of justice a criminal court can achieve.

“The sentencing is a tricky matter. There is no just sentence when it comes to mass crimes. It’s an impossibility, so depending on whose point of view and interests you consider, you are going to strike a balance between irreconcilable factors. In absolute terms, a life sentence seems to be the only one available for 14,000 deaths or more, but sentencing has never worked in absolute terms before other war crimes tribunals: it’s a balance between a number of factors, including the expression of guilt and remorse, the cooperation with the judicial system, etc. That’s why many genocide convicts got lesser sentences before the Rwanda Tribunal, for instance. In that sense, the Trial Chamber in the Duch trial had reached a much more consistent sentence than the absolute one the Appeals Chamber gave. But that has probably hardly anything to do with ‘justice’, certainly not with how it is felt and understood by most victims and civil parties.”

What was the author’s impression of Duch at the beginning of the trial and how did it compare at the end? “My impression – and it’s only an impression, only he knows – is that he came to realise during the trial, and more precisely after the week during which civil parties came and testified and refused him the forgiveness he had naively hoped for, that he wouldn’t get much of what he had wished from the process. As I describe it in the book, there is a striking change in his physical behaviour by the end of the trial. And there is his endorsing Kar Savuth’s absurd and self-damaging move (the defence co-lawyer presented an argument near the end of the trial that Duch should be acquitted).

“To some extent you could say that something broke in him. I don’t think he was broken, but he clearly withdrew. He was silently upset, somehow. I think it’s because he realised that he wouldn’t get what he had hoped for – a measure of redemption, or something along these lines – or what he had been perhaps made to hope for by others. One also has to keep in mind, always, the exhaustion that comes with a trial for anyone who’s in it and for the accused more than anyone else. That’s a factor that is very often ignored, but it’s real. Beyond his exceptional physical and mental strength, Duch could only be exhausted at that point and that also had changed him.”

In Master, Cruvellier mentions more than once the fact that Duch failed, for whatever reason, to destroy the enormous number of files accumulated at S-21. How differently would we judge the Khmer Rouge today if those files, including the thousands of photographs, had been destroyed?

“I believe some of the most respected historians, including David Chandler, agreed that our knowledge of the Khmer Rouge system would be significantly, or even dramatically, less if it wasn’t for S-21 archives. I do not think that the way we judge the regime would be much different, but our knowledge of the system as well as the capacity to bring some of them to court – first of all, Duch – would be very different.”

And what of the progress of the trials under Case 002? “I haven’t followed in detail the proceedings in the second trial, so I can’t comment on their inner value and quality. One obvious observation, though, is that the process has heavily deteriorated after the completion of the Duch case. All international tribunals deteriorate with time; that’s a sad reality. But the time taken to run a first mini-trial in Case 002 that hardly looks into the most serious crimes committed is a disgrace, and the cost related to maintaining all organs of the tribunals working over the past four years on that single case and on the hypocritical handling of cases 003 and 004 has clearly brought to question the integrity of the process.”

Turning the final page of Master, I’m left with one beguiling reflection: perhaps, in the end, Duch represents the Khmer Rouge’s ultimate ‘victim’? A man who believed in its original ideals and was then obligated through personality, fear and his own foibles to continue serving its ‘revolution’, even as it turned in on itself and devoured the people it had vowed to set free. As Cruvellier eloquently writes: “Sometimes broken dreams are like revolutions: they turn into nightmares.”

Master of Confessions: The Making Of A Khmer Rouger Torturer, by Thierry Cruvellier, is available from Monument Books now for $25.

Great book! Provides us another angle to access knowledge of the history of Khmer Rouge.

Thank you, Wayne, for writting a very informative and valuable review.

Ok! Interesting review. I will add to my reading list.

I have read a couple of books on Duch’s story, including Nick Dunlop’s, but this sounds like a good addition to his story.

Dunlop’s book is indeed excellent. Together with Bizot’s ’The Gate’ it

adds more colour & detail to Duch’s story.