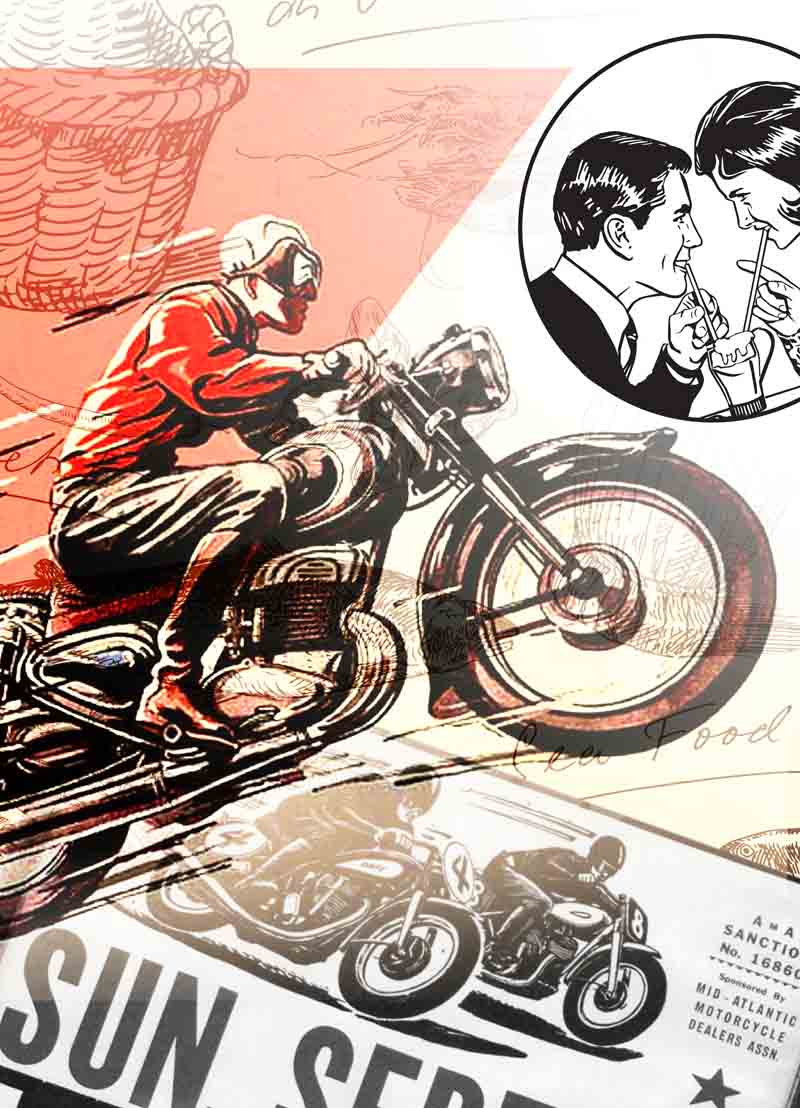

In 1953, the sight of a young, leather-clad Marlon Brando astride a motorcycle in The Wild One sent most decent folk into a collective, self-righteous tailspin. The movie was immediately outlawed in the UK, where it stayed on the black list for the next 14 years. Too late: biker-gang leader Johnny Strabler’s soulful menace, that ultimate-for-the-time icon of restlessness and rebellion, had burned deep into the collective subconscious. And replicating that image on the streets swiftly became about something more than skin-deep. Legend has it that, in London during the 1960s, riders would select a song on a cafe’s jukebox then race off on their Triumphs, BSAs and Nortons, returning before the track finished. These greased-up rockers often clocked speeds in excess of 100 miles per hour – rare at the time, hence ‘ton-up club’ – by stripping all but the essentials from their machines, which were little more than a seat on wheels. With custom cafe racers now on Cambodia’s streets, The Advisor meets those magnificent men of Moto Cambodge and their riding machines to talk fast bikes and slow food.

How did you cafe racers find each other?

Patrick Uong (Cambodia/US brand manager): Once upon a time I moved back to Cambodia from NY and was in search of a bike. Happened to be told about Paul Freer. The very next day I was walking down the street and saw Paul on what is now my bike. It’s an early ‘90s Yamaha SR400, all blacked out, nice and fierce. Really badass. I saw Paul on it and he has this white hair and wears spectacles and braces.

Justin Stewart (Australia, animator): My son calls him ‘That English chap’…

Patrick: He was wearing a white linen vest and spats! I contacted him, bought the bike and then met a lot of other guys who’d bought bikes from Paul. We realised there was this little contingent of us. The platform of the SR400 lends itself very easily to transformation.

Nick Chandler (New Zealand, marketing): The SR400 is like the foundation of motorcycles: it started as single-cylinder and hasn’t really changed since. Single-cylinder, big-bore, torque-out thumper, mid-size engine. You can make a tracker, you can make a racer; all the styles we’re into.

Patrick: I started riding about 14 years ago in San Francisco, old ‘80s plastic BMWs. They’re so easy to work on – none of this supercharged engine stuff, just pure animals of joy. You get to tinker with them, or someone else tinkers with it for you, and it’s not incredibly expensive.

Nick: It’s like a lawn mower! The SR really is that simple: it’s a carburettor, a fuel tank, an engine, a gearbox and a sprocket. Nothing fancy.

Patrick: And the kickstart. Don’t forget the kickstart! And the SR was modelled on the BSA – it’s a better version of the old English BSA.

Justin: There’s one newer bike in our fleet, but we prefer bikes from the ‘70s. I was massively into dirt bikes in Australia then came here and saw Paul’s bike. That was my transition into road bikes. I now have an SR400 Tracker; the CL450 ‘70s bike, stock, and the BMW K100 RS, which was just an opportunistic thing –it was really cheap and really ugly and I knew we could chop it up!

Patrick: Paul has this really distinct style; he gravitates towards these old, oily machines. Paul is a British riding gentleman. He would wear wool knickers right now if he could! When I built my bike, I hadn’t seen a single cafe racer in Phnom Penh. Ever since I started riding, I’d always wanted one.

Nick: Yours is probably one of the most distinctive SRs I’ve ever seen, Patrick. It doesn’t look like anything else. You know what people say about their pets? If you were a motorbike, you’d be your bike.

Patrick: I put a lot of sweat into it!

Nick: I come from a motocross background, so I always put straight motocross bars and knobbly tyres on my bikes. I do like cafe racers as well, though: stripped back, clip-on bars for speed, rear sets so you can lie down on the tank. It started in the UK. Guys were coming back from the war with their stipend from the army. ‘What am I going to do now? I’ll buy a bike!’ That’s how the Hell’s Angels got started in the US. In Britain, mods and rockers would race from cafe to cafe, trying to hit 100 miles per hour. The easiest way to make a bike faster is to strip weight off and that’s coming back now; the number of people talking about cafe racers is growing fast. There’s something about that simplicity that people are going back to. And being on a motorbike is the ultimate freedom.

Have you ever read Zen & The Art Of Motorcycle Maintenance?

Everyone: Yes!

There’s something rather special about messing about with bikes. When it comes to customising a machine, is it a psychological exercise as much as a physical exercise?

Nick: Look around the table – we’re all dressed a certain way that’s representative of ourselves and that’s perhaps a conscious decision, but with a motorbike it’s almost like looking in a mirror without knowing that’s what you’re doing. Like I said, if Patrick was a motorbike, he’d be HIS bike. I like dirt bikes and they originated from Steve McQueen and co grabbing their Triumphs, taking them off road and racing them.

Patrick: Steve McQueen for us is an icon.

That famous scene in The Great Escape, when McQueen’s character, Hilts, jumps a border fence on a Triumph TT Special 650, was added by the director especially for McQueen, a known speed-freak and petrolhead.

Nick: Have you seen the 1971 documentary On Any Sunday? McQueen was an absolute nut job. All he wanted to do was ride bikes. It’s an expression of self: with a motorcycle, it’s you and only you. It’s a selfish purchase. If you buy a car, you have to put up with other people. You establish a relationship with a motorbike.

Justin: Motorcycling, for me, is surfing when I can’t surf.

Being a fighter pilot when you can’t be a fighter pilot.

Patrick: Surf culture, skate culture, motorcycle culture: they go hand in hand.

Nick: You sit down with a mate and talk about what you want to do with the bike, plan a road trip…

Patrick: That’s motorcycling: it’s you, your mates, your machine, the journey.

Nick: A lifestyle! People accept each other simply because they both ride motorbikes.

Patrick: We were talking earlier about what makes a cafe racer. It’s usually the lines: the shape, the form. It’s very straight, horizontal; cut like a bullet.

Calls to mind New Zealander Burt Munro, played by Sir Anthony Hopkins in The World’s Fastest Indian, who set the land-speed world record in 1967 on a bike he built by hand in his garden shed.

Nick: Exactly! And that’s the point of motorcycling: anyone can do it. They’re cheap to buy, cheap to own and simple to work on – if you want them to be [Laughs]. I can’t remember the last time I went on holiday with someone else. I usually just fly to Colombia, Sri Lanka, anywhere, rent a bike and spend 14 days riding around. It’s a visceral experience; you’re exposed to everything around you, so you get to experience your environment. That’s what Moto Cambodge is about: we get together, talk about what we’re going to do to our bikes, do it, then go out and ride them. And we can do it right here, in Cambodia: create something world class in a town where the power still goes off once a day.

Tim Bruyns (South Africa, chef): For me, it’s the same as these guys and their bikes: taking all these influences and bringing them to Cambodia, using them, and putting their experiences and how they feel about bikes into a Cambodian context. At Common Tiger, just about everything is sourced from local markets, but our food isn’t ‘Cambodian’, it takes everything that I am and I’ve experienced and puts it altogether on a plate. We had one prawn dish with handmade cannelloni: it had red curry, which is Thai; it had a confit garlic and lemongrass espuma, which is modernist. So there are all of these influences, but at its core it’s a product of passion and its environment. It’s like working on a motorbike, you miss out on other things; it becomes so much a part of who you are. Working with food, it’s the same and we also tend to gravitate towards like-minded people. Between the two disciplines, there are many similarities and that’s why we’re all here, which is good!

Patrick: Tim cooks from his heart and that’s how we feel about our bikes. We’re all super-passionate about what we do and we hope that other people catch on too. When Tim comes to the table and talks about the food he’s prepared, in his voice you can hear how passionate he is about what he’s created for you – ‘This is what I made for you!’ – but being very humble about it. I would like to portray Moto Cambodge as humble, too. We’re not hot shots, we’re guys who like to ride bikes and talk about bikes and tinker with bikes and go find bits and then build and construct and fabricate, you know? It’s about substance and aesthetic, the same way a chef composes his plates. Think about how much he has thought about that. That’s what we also bring to custom bikes: we really, really think about what it’s going to look like; we envision everything. It takes months to build one – and so much planning.

Tim: That’s why taking old bikes and bringing them into the context of who you are and where you are is so awesome. When you start as a chef, you earn $200 a month for six to seven years because you’re learning about what’s gone before and learning that gives you the tools to go forward. I’m always looking through 19th century recipes; early 20th century recipes, everything, because it was awesome then and it can be awesome now, but I’m going to take it and put it into the context of Cambodia.

Nick: And make it accessible, which is what you’re both good at.

Tim: People have this idea of what fine dining is, but Common Tiger isn’t excessive; it’s nothing over the top. Chill out in a comfortable chair. Our most expensive dish is $14; we haven’t even got tablecloths! [Laughs] Food should be about sitting around and being in a position to talk about bikes, to talk about whatever and enjoy it.

Patrick: Food, like bikes, is about bringing people together.

Tim: And with these guys doing what they do, why not just put the two together and do something different and fun, put some love into it?

WHO: Cafe racers

WHAT: Fast bikes & slow food

WHERE: Common Tiger, #20 Street 294

WHEN: 6pm May 9 – 10pm May 11

WHY: “On my tombstone they will carve: ‘IT NEVER GOT FAST ENOUGH FOR ME.’” – Hunter S Thompson