Their scientific names conjure bizarre images of otherworldly creatures from outer space: Hippocampus hippocampus, Dugong dugon, the highly improbable-sounding Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda. And indeed they are of another world, but not outer space. Rather its terrestrial equivalent: the lesser-known ‘inner space’, otherwise known as the World Ocean that covers roughly seven tenths of our blue planet.

Despite containing 97% of the world’s water, only five per cent of said ocean has thus far been probed by the prying eyes of man. This strange, sub-aqua world has long been one of great mystery to us landlubbers; source of many a seafarer’s tale of boat-eating beasts and fair maidens with fish tails. And where might one set coordinates to find the highest concentration of such underwater wonders? Avast, me hearties! They be right here!

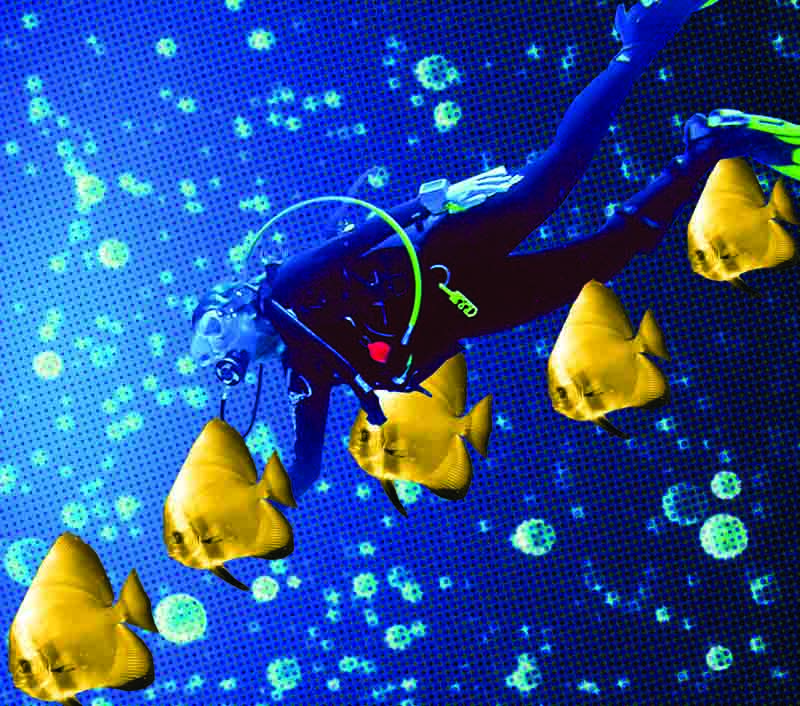

The Koh Rong archipelago is home to a vast array of endangered marine life, from ethereal-looking seahorses (the aforementioned Hippocampus hippocampus) and mermaidesque manatees (Dugong dugon) to prehistoric horseshoe crabs (the Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda) and rare-as-hens-teeth turtles, both green and hawksbill. All are on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; all, if you’ve been courting good karma and can snorkel or scuba dive, can be spotted merrily going about their business beneath the waves of Cambodia’s seas.

The reason they can be spotted merrily going about their business is that, for the past few years, various marine conservation agencies based on the Cambodian coastline – which, running between Thailand and Vietnam, boasts more than 69 islands – have pulled together in a convincing show of solidarity to shunt these creatures, and the watery habitat in which they live, as high up the political agenda as possible.

Song Saa Foundation. Fauna & Flora International. Conservation Cambodia. Coral Cay Conservation. The Fisheries Administration. Everyone came to the table. Among the outcomes are the country’s first Marine Fisheries Management Area, which when approved later this year will cover 340 square kilometres and surround every island in the archipelago; the creation of more than 100 artificial reefs; the first scientific surveys of Cambodia’s marine habitats, and – every step of the way – the respectful nurturing of local folk who depend on small-scale fishing to put food in their mouths (only 15% of Cambodia’s fishing is done in the sea; the rest is inland fisheries).

It wasn’t easy. Dynamite and cyanide fishing, bottom trawling, hazardous waste, boat anchors, poachers: all conspired – and, in some cases, continue to conspire – to destroy Cambodia’s coral reefs, seagrass beds and mangrove forests. Local fishermen note that their catches are becoming ever smaller. Dr Wayne McCallum, director of sustainability at Song Saa, makes reference to the terrible implications of mass tourism: “In Thailand, things have been lost.” He sighs and kicks the sand, crestfallen.

But here on the grey concrete helipad jutting into the ocean from the fishing community of Prek Svay, a jolting, five-minute skip in a long-tail from neighbouring island Song Saa, there is still much to celebrate. It’s World Oceans Day, June 8, and the helipad is crowded with local children, officials and a one-man camera crew from CTN. Almost everyone is wearing their light blue World Oceans Day T-shirt and matching baseball cap, trying not to fidget as another speech gets underway.

Our agenda for the day includes an up-close inspection of some prime sub-aqua real estate; the premiere of Coral Cay Conservation’s new documentary on marine life in the archipelago, from which the headline of this article is shamelessly stolen; the presentation of a new patrol boat to a local fisheries committee, and a video guide on how to build an artificial reef (not as easy as it sounds, as it turns out: maintenance includes divers removing algae – which prevents sponges and corals from growing – using a toothbrush).

Interestingly, it’s the Coral Cay documentary that finally silences the group. Designed with local communities in mind, the film offers a view of the Cambodian seas that few of its countrymen have ever seen: the view from the bottom up. It’s also a view that’s vital to nurturing better local understanding of Cambodia’s underwater wonders and why they should be preserved.

“Too often we’ve witnessed sacks full of garbage thrown from over the side of boats,” cautions Ben Thorne, of Coral Cay Conservation. “Likewise, there are large amounts of ‘ghost nets’ on the reef; nets which were used for fishing, but now lay dormant and neglected over healthy patches of coral reef, often enclosing fish too. The proposed Marine Fisheries Management Area and ongoing bio-physical surveys by the Song Saa Foundation aim to reduce these pressures. It is noticeable, through events such as World Oceans Day, that locals are becoming more conservation-savvy regarding their impacts on the reef. Let the good work continue!”

Bora, a 34-year-old from Kandal province with an easy smile and near-perfect teeth, knows this. He’s Cambodia’s first native scuba diving instructor, a badge he wears with pride. Introducing himself as precisely that, with a firm handshake and lingering grin, Bora – long hair tucked up beneath his blue Oceans Day baseball cap – stretches his legs out beneath the table. Behind us, on the dressed-for-the-occasion pier, the sons and daughters of Koh Rong Saloem fishing families are racing each other on tiny rafts made of recycled materials: empty water bottles here; Styrofoam boxes there. The crowd cheers.

What does Bora think about being the first Cambodian scuba instructor? “I love it! In the beginning, I didn’t want to do it. I’d heard the instructor’s exam was very hard and my English wasn’t great. It took me a long time to finish my Dive Master (a prerequisite for the instructor’s course). I was worried about two things: physics and physiology. My boss at the Dive Shop was worried too, but in the end I got 100% in both exams!”

Such achievements are not to be underestimated in a country where, although many grow up swimming in rivers, few are bold enough to brave open water. “I wasn’t afraid; never!” says Bora. “In front of my house there’s a river, so when we were growing up we used to swim a lot. I got invited out to Koh Tang on an overnight boat trip once to go diving – my first time. I called my boss at Friends International, where I worked as a teacher, and told him: ‘I need to go. I cannot stay in Phnom Penh any more.’ I had fallen in love with being at the bottom of the sea. I love the fish! I’ve seen turtles two times here in Cambodia and I helped release one from a village, where people had caught it in a fishing trap.”

As a professional scuba diver, Bora is well versed in the importance of protecting the sea and those who dwell in it, but the message is still new to many Cambodians (his own parents don’t know what he does for a living: “They would worry too much about sharks and burst eardrums,” he says). “We found an empty turtle shell once while we were diving. I don’t know who had killed it; perhaps Vietnamese or Khmer fishermen. So we were carrying this shell and it suddenly occurred to us that there might be a bull shark watching, thinking it might eat the shell for lunch… A lot of people from Phnom Penh, they don’t like to swim in the sea. If they see a shadow behind them, it must be Jaws. But we only have two sharks here in Cambodia: the bamboo shark, which is tiny, and the whale shark, which has no teeth!” [Laughs]

“In some villages, you can still buy shark and stingray in restaurants; they’re just not openly advertised on the menu,” Bora says, noting that the only good thing is that, unlike China, where only the fins are taken and the rest of the shark is left to die in the water, here in Cambodia people eat the whole thing. “Some people here, even the younger ones, they don’t really want to learn. But when people find themselves getting better jobs with companies like Eco Sea and start working with foreigners, then they start to understand why what we’re doing here is so important.”

Important it most certainly is. No Take Zones, in which fishing is banned, allow endangered fish populations to stabilise and, left undisturbed, thrive. When that happens, some of those fish – given their newly bolstered numbers – will spill out of those protected areas as what the Science Brains call ‘exported biomass’ and into the nets of local fishermen, thus keeping catch levels up and establishing the kind of cycle that’s actually sustainable.

Sustainability, of any hue, comes of course at a cost. In the case of the coral frames being made by marine conservationists at Frontier on Koh Rong Saloem, each of which will one day house a bustling reef system, said cost amounts to $89 per year, per frame (ongoing surveys, cleaning, paying dive teams). In one particularly noble gesture, once Frontier has finished giving its World Oceans Day presentation, Fisheries Administration Director General Dr Nao Thuok – sporting a particularly splendid comb-over – reaches into his pocket and produces a crisp $100 note. “No need change,” his excellency nods, beaming. Five other fisheries officials swiftly follow suit.

The final word goes to Bora: “More Cambodians are starting to dive now and we even have a Cambodian Dive Master at the Koh Rong Dive Centre. I really want to see more Cambodians scuba diving and I want to be the one to train them. As long as there’s scuba diving here, I’m not going anywhere. I feel happier at the bottom of the sea than I do on land.”

Check out more at: http://www.songsaafoundation.org and https://www.facebook.com/songsaafoundation?ref=hl. The fb page includes wonderful shots from WoD 2014, including close-ups of that comb over 🙂 Enjoy.