Author Gea Wijers asks: Why do so many Cambodian-Americans chose the NGO path as part of their reintegration strategy, while returnees from France seek to work within the Cambodian government?

“In my experience, your life is like a log floating down the river where the flood was taking place. You just go with the flow. You have to navigate by what you can see. You have to navigate a river by its bends.”

– Cambodian-American returnee

Two days ago I had a mind-jarring, sweat-inducing flashback. No, I wasn’t being jammed into a 4x2ft locker by the strapping, laughing boys of my old fifth-form school, me a hapless and as it turned out very malleable third-former.

And no, I wasn’t playing on the wing of the local rugby club’s 10th 15 team (the Siberia of rugby positions in the Gulag of teams, reserved for those for who the gap between ability and enthusiasm was about as wide as the Mekong), with the ‘son of Jonah Lomu’ looming down on me like a bulldozer on meth.

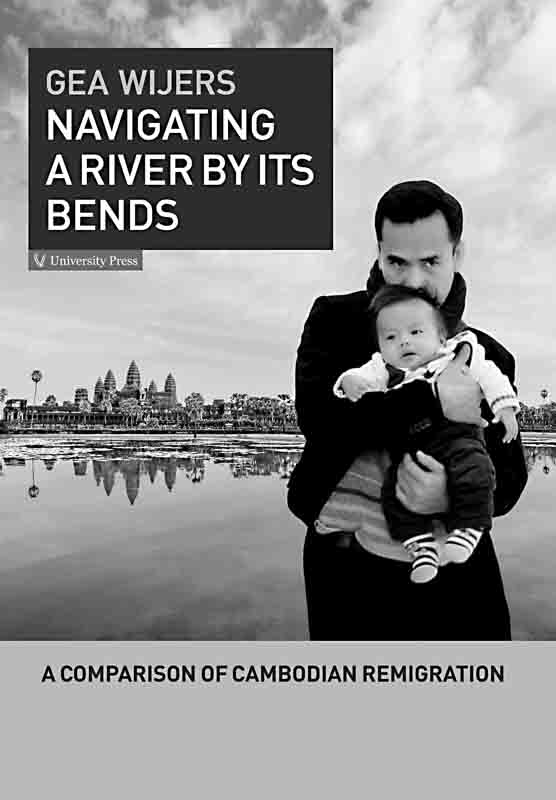

No, the cause of my view into the rear-vision mirror of life was Gea Wijers recently published book Navigating A River By Its Bends. You see, no matter how interesting and informative Ms Wijers new book, one cannot escape the fact that, beyond the bright cover, the whole thing is styled and written in the form of the PhD study that her book is based on. And as a man who closeted himself in a room for five years working on his own doctoral mishmash, I’m not convinced this is a world of literature I wish to reintegrate myself with anytime soon.

And this, as it turns out, is a bit of a shame, because if you can go beyond the issue of presentation and language, Navigating A River By Its Bends is actually a damn interesting read. It’s just not the most attractive or accessible format by which to enter into the author’s topic.

Beyond these misgivings, what’s the book actually about? Subtitled A Comparison Of Cambodian Remigration, the book sets out to explore the strategies that American-Cambodian and French-Cambodian returnees employ to reintegrate into Cambodian society and some of the social and institutional challenges they face in their efforts to accomplish this.

Behind this focus is the research question that originally inspired the author, namely: why do so many Cambodian-Americans, upon their return to Cambodia, chose to establish NGOs as part of their reintegration strategy, while those from France seek to work within the Cambodian government (like me, you probably know returnees from both countries who fit neither of these categories, which suggests that Wijers question is more of a generalisation than a normative reality)?

Given this premise Wijers uses the theoretical lenses of entrepreneurship and social capital to drill deep down to explore the worlds of returnee integration. After all the ensuing data collection and analysis, what emerges is a picture of how complex and challenging it is for returnees to shape their new lives and find new opportunities in the Kingdom; a challenge that persists despite the range of skills and experiences they bring back with them.

Driving this challenge, Wijers suggests, are elements of suspicion, social legitimacy, trust, acceptance and understanding (among other things), which conspire to thwart the capacity of returnees to become positive change agents in their ‘new’ home. Moreover, as the ties with their former country evaporate and the challenges of establishing new ones in Cambodia persist, many returnees experience feelings of exclusion and alienation.

By illuminating these processes, Wijers offers an appreciation of the implications for the parties involved, including the ‘lost opportunities’ for Cambodia – denied the full potential of the human capital that the returnees have to offer. And the personal frustrations of the returnees themselves, many who return to the Kingdom with high hopes and aspirations only to find them stymied by walls of social and institutional resistance.

Unsurprising, what this means is that Navigating A River By Its Bends is likely to have genuine appeal to those working in the subject area or who have a broad interest in the humanities as they relate to Cambodian society. Meanwhile, for those who come with a more casual attitude toward the topic, be prepared for a solid mental workout.

Whatever decision you make, just don’t expect any pictures.

Navigating A River By Its Bends: A Comparison Of Cambodian Remigration, by Gea Wijers, is available from Monument Books for $39.50.