“Cambodians who lived through this period refer to it in different ways… one such phrase is neuv pel porpok thlak pi leu mek, or ‘the time when the clouds fell from the sky.’”

“Cambodians who lived through this period refer to it in different ways… one such phrase is neuv pel porpok thlak pi leu mek, or ‘the time when the clouds fell from the sky.’”

Several recent books have tackled the most vexing questions – the how, what and why – of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge past. They include Rithy Panh’s The Elimination and Thierry Cruvellier’s The Master of Confessions. Robert Carmichael’s When Clouds Fell From The Sky is the latest effort and could well be the best of the crop.

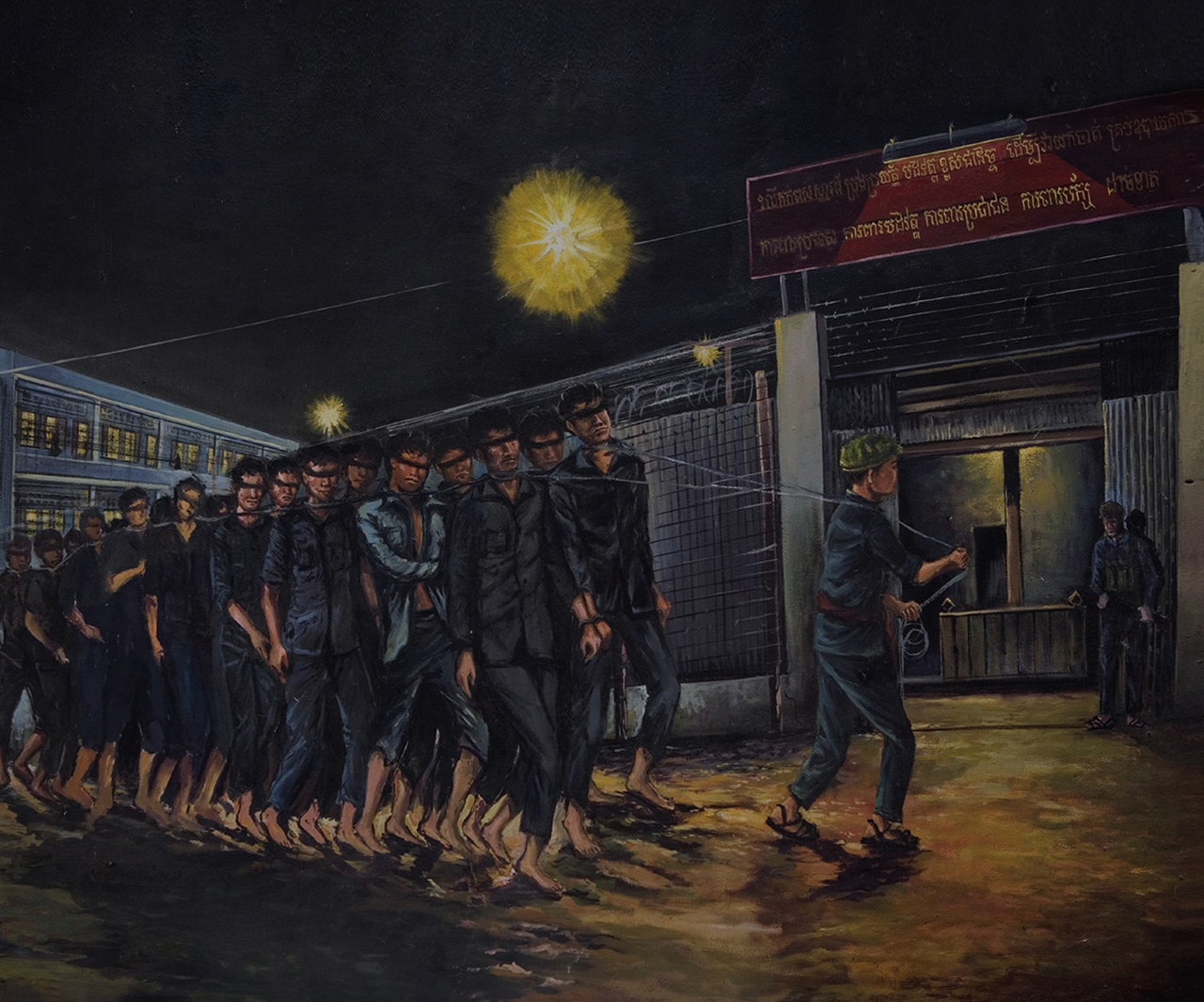

At the centre of Clouds is the fate of Ouk Ket, a Cambodian diplomat who in 1977 received instructions from his Khmer Rouge masters to return home for “re-education.” Like other returnees, Ket came back to Cambodia optimistic about the future, leaving behind a wife and two children who, it was planned, would join him soon after. But then, after a final postcard, nothing. Ket simply disappeared.

From this beginning Clouds divides much of its story between the efforts to uncover the truth around Ket’s fate and the events surrounding the trial of the man who approved his eventual execution: Comrade Duch, the commander of S-21. To frame his story, Carmichael uses the experiences of those affected by these events, including Martine and Neary, Ket’s wife and daughter. Inevitably, the story features numerous twists, turns and personalities, which climax around the verdict and sentencing of Duch.

Carmichael draws on an impressive range of sources and interviews in Clouds, leaving few stones unturned as he weaves together events of the past, with the efforts by its victims to reconcile with its legacy. Yet, sometimes it is the little things the author notes that are the most intriguing. This includes the way that Duch would pour and drink a glass of water while seated during his trial. Meticulous and exact, Carmichael speculates about the events that led Duch to develop such precise behaviour, while wondering what it tells us about the man who so diligently recorded the fate of S-21’s victims in its infamous photographs and files.

Above all, Clouds reminds us of the positive strengths of Khmer character – dignity, reverence, defiance – and, tellingly, the capacity of people to do evil. Yet beyond this, turning the final page, it is the light of Ket’s memory carried by friends and loved ones that reminds us that respect and love can surpass evil. Affirming this could be Carmichael’s greatest triumph and the nugget of hope that lies at the centre of his tale of tragedy and reconciliation.

5 out of 5

Q&A

What is the history of Clouds? When did the idea come to write it and why did you choose to tell the story through the story of Ket?

RC: I decided on it in 2010 and wrote the first draft over eight months in 2011. That was preceded and followed by lots of research and interviews and, of course, rewriting. All told, it took a little under two years. The story of Ket’s disappearance – and the impact that had on Martine and Neary, both of whom are French – is a powerful one and mirrors the experience of millions of Cambodians.

Parts of Clouds, especially Duch’s trial, are reminiscent in form and story of Thierry Cruvellier’s recent book The Master of Confessions. Interestingly, you do not cite this work among your numerous references. Was this simply a matter of timing or is there another reason?

RC: Nothing more than timing. My book was completed by the time Thierry’s was published in English.

There are some excellent images in Clouds that add to the story, but two prominent photographs referred to in the book do not feature: the one taken of Chan Youran in the Geneva park and Ket’s (suspected) S-21 photo. They seem to be key images, so what was the rationale for their exclusion?

RC: The Chan Youran photo isn’t potent (though the story behind it is) so I discarded it. As for the other: both Martine and Neary believe the image shown at trial is Ket but – and this is a very sensitive subject, of course – I’m not convinced, so I omitted it. That said, there’s no doubt Ket was held at S-21 and was later executed – the prison records prove that. Many prisoners’ photographs have disappeared since 1979.

Having completed Clouds, what for you were the biggest lessons learned about Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge legacy?

RC: That as political systems become less accountable, the dangers for their citizens increase rapidly. In Cambodia’s case, the leadership’s paranoia, brutality, incompetence and their utter negation of the worth of the individual were embedded into a system of zero accountability. It doesn’t get more dangerous than that.