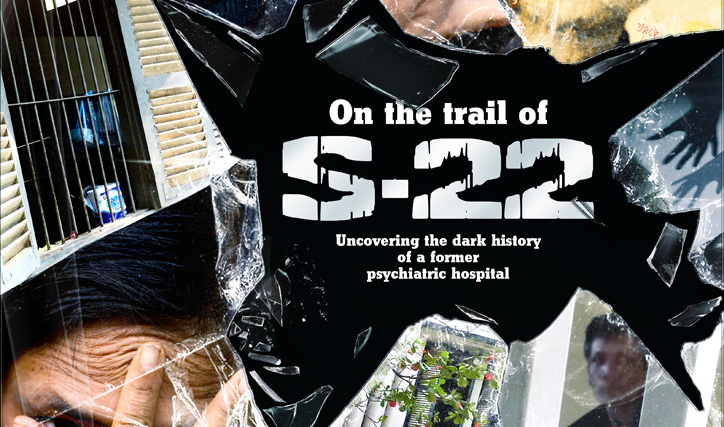

No visitor could possibly leave Phnom Penh without having at least heard about S-21, aka Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, one of the country’s most famous historical landmarks and tourist destinations. S-22, however, is shrouded by a shady history, which continues to conceal it from the collective consciousness.

Everyone knows S-21, or the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, the Khmer Rouge prison and one of the most famous tourist attractions in Cambodia. But not many people have heard of S-22.

Yet, a place with a code name S-22 is included in the list of crime sites in the Khmer Rouge Tribunal’s case 003. Case 003, which is opposed by the Cambodian government, brings charges against a Khmer Rouge navy chief and an air force chief, who is now deceased. According to documents from the tribunal, around 300 prisoners were held at S-22.

“Some prisoners were identified as having committed ‘light offense[s]’ whilst others were implicated as having a connection in the ‘enemy string.’ The prisoners were provided only one meal a day,” the documents state. “Their ankles were shackled and they were made to work digging earth and clearing grass within the compound. They were also made to do work outside the compound, building a dam and dike, along with rice farming.”

The prison was operated by the Division 502 of the Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea, and the people imprisoned inside were also members of Division 502.

But what was the significance of this prison, which seems relatively small compared with Tuol Sleng, where an estimated 17,000 were murdered? And where exactly was S-22 located?

According to Lars Olsen, the spokesman for the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, S-22 is in the Meanchey district of Phnom Penh. However, the prison’s address has not been made public.

It was Robert Petit, the Canadian co-prosecutor who resigned from the tribunal in 2009, who asked for S-22 to be included in the list of crime sites in case 003. But Petit, who is currently employed by Justice Canada, said he is not in a position to answer questions from the media.

Meanwhile, Youk Chhang, the director of the Documentation Centre of Cambodia, a depository currently holding the largest number of documents from the Khmer Rouge era, says that S-22 was the old psychiatric hospital in Ta Khmao, the capital of Kandal Province about 30 minutes outside of Phnom Penh.

During his trial at the tribunal, the former director of the Tuol Sleng Prison, Kaing Guek Eav (better known by his alias “Duch”), also referred to S-22 as a psychiatric hospital in Ta Khmao. When questioned about what happened to the mentally ill patients there during Pol Pot’s time, Duch told the court they were probably killed.

“I am not clear, but I would like to give you my analysis in comparison to those who get leprosy. In Sector 15, those leprosy people were smashed, ordered smashed, and the upper echelon ordered to smash all those who get leprosy,” Duch told the court in April of 2009. “I’m more than 15 percent [sure] that all the patients at the psychiatric hospital were smashed.”

The psychiatric hospital

The psychiatric hospital in Ta Khmao was the only psychiatric hospital that Cambodia ever had. Once known as the Prek Thnaot Psychiatric Hospital and later as the Sok Mam Hospital, it housed mentally ill patients from 1955 until 1975.

There was a ward for patients with tuberculosis and a building for (possibly mentally ill) monks. It was a hospital, but in some ways it was similar to a prison because the patients weren’t allowed to leave. The windows had bars on them and, as one of the local residents remembers, the guards would beat the patients if they tried to escape.

Today, the old psychiatric hospital in Ta Khmao still treats patients, but it’s no longer a psychiatric facility – although there is a day clinic for children and teenagers with mental health problems. The compound is now known as the Chey Chumneas Referral Hospital.

On a Sunday afternoon, it is a peaceful place with rows of coconut trees and children running around on a playground. There is a man-made pond that looks like a swimming pool from a distance. Ducks stroll through the hospital grounds. The walls of the paediatric ward are painted with cheerful images of an ant riding on a motorcycle and a dinosaur saying hello to a rabbit. The busiest ward is the one where women give birth, judging from the pile of shoes near the door.

Yet, look closer and you might notice some remnants of a dark past. The windows of the older buildings have bars on them, starkly resembling those at Tuol Sleng. The hospital rooms are fitted with padlocks, which can be locked from the outside. Indeed, one of the rooms at the end of the paediatric ward is still used as a prison cell. Ill inmates from the Ta Khmao prison stay here, says the prison guard who sleeps in a hammock outside.

According to Pheng Pong-Rasy, who wrote a report about the Khmer Rouge prison at the hospital for the Documentation Centre of Cambodia, five years ago you could still see the shackles in some of the hospital’s offices, and holes in the wall which were used for the prisoners to urinate. The coconut trees – about 130 of them – were planted by the Khmer Rouge on top of mass graves.

“Those coconut trees were not there during Sihanouk and Lon Nol regimes,” Rasy reports, based on interviews with survivors. “The Khmer Rouge would plant coconut trees on the spots where they buried the bodies in the belief that the corpses would become a good fertiliser… Currently, all the coconut trees grow surprisingly well.”

The Khmer Rouge converted the hospital to a prison for air force soldiers who did something wrong, Rasy says. For instance, one man was taken away for having sex with a woman in his unit.

Unlike Tuol Sleng, there are no written records, photographs or confessions at S-22, so the only way to know what happened is to gather the memories of survivors – or perpetrators.

There is also no memorial here and no human skulls on display as there are in S-21. The reason there is no memorial, according to Rasy, is because comparatively few people were executed here: “only hundreds, not thousands.”

The memories

On a recent afternoon, information gathered from interviews with locals in the area pointed to the home of 92-year-old So Rein, whose children sell bread near the hospital.

On a recent afternoon, information gathered from interviews with locals in the area pointed to the home of 92-year-old So Rein, whose children sell bread near the hospital.

Rein, who was born and raised in Ta Khmao, says he worked as a night guard at the hospital soon after it reopened in 1979.

“I saw shackles and blood… At night, the smell was bad inside the buildings from the blood of the people, and I couldn’t sleep well because of the smell,” he says. “I felt bad because of the smell of blood, so I’d get up and smoke a cigarette. When the rain came, the smell would get really bad.”

Rein (whose job also included cremating the bodies after patients died in the hospital if their families didn’t claim them) says he heard that the Khmer Rouge took some of the psychiatric hospital’s patients in cars to Pich Nil waterfall on Route 4, where they were executed. Afterwards, the hospital was cleaned and converted to a prison.

Upon being asked whether he witnessed the execution of the patients, Rein says that he only heard about it from his friends.

Rasy heard a different story from Daok Sok-Kai, a former hospital worker who pretended to be mentally ill to survive the ordeal. Some of the psychiatric patients at the hospital were killed because the Khmer Rouge mistook them for Lon Nol soldiers, Sok-Kai told him.

“The Lon Nol soldiers dropped their uniforms [when they realised they lost the war]. The people in the hospital didn’t know [any better], so they put on the clothes,” recounts Rasy. “When the Khmer Rouge saw this, they brought them to be killed [because they mistook them for real soldiers].”

Another longtime hospital employee, Say Penh, who began working at the Chey Chumneas Referral Hospital in 1979, told Rasy that the prison was used to detain handicapped people who used to be high-ranking officers, and that they were forced to dig three wells into which the bodies of Khmer Rouge victims were thrown.

Conflicting information

While the Documentation Centre of Cambodia insists that S-22 is the old psychiatric hospital in Ta Khmao, and Duch said the same during his testimony on April 27, 2009, by June 24 of that year the code numbers in his memory switched places. As a result, at the end of June 2009, he stated that S-22 was a fruit farm “somewhere in Ta Khmao,” while the psychiatric hospital was known as S-23, according to court transcripts. S-24 was the Prey Sar prison, he told the court.

Meanwhile, Cambodia Daily newspaper, in an article dated May 10, 2011, refers to S-22 as “an air force detention centre in Phnom Penh’s Toek La’ak area,” which was under the direction of Khmer Rouge air force commander Sou Met (a suspect in case 003, who has since passed away).

So, was S-22 the old psychiatric hospital, a fruit farm, or an air force detention centre? Was the air force detention centre on the campus of the former psychiatric hospital? Was S-22 in Ta Khmao or in Phnom Penh?

Tribunal spokesman Olsen continues to assert that he doesn’t have the authorisation to clarify the confusion.

But perhaps the answer doesn’t matter. Whether the Khmer Rouge prison at the psychiatric hospital in Ta Khmao carried the code name S-22 or S-23, it doesn’t change what happened there.

Julie Masis organises visits to the Khmer Rouge tribunal. For more information, email her at greenelephant888@nullgmail.com