There was no speedometer. The brakes were as responsive as boiled vegetables and the wing mirrors flapped in the wind. How fast was I going? Hell, I couldn’t even remember if the hired Honda Baja had five gears or six. The world blurred. Scooters and cars fell away. This was too fast. Visions of accidents appeared in my mind, the road strewn with blood and stumps. Must focus. Use all available brainpower. Divert maximum attention to the road. Apart from the small amount of attention needed to headbang to Clutch’s Blast Tyrant album that was being piped into my head at an ear-maiming volume. It was the only way it could be heard over the squealing wind as I drove to Siem Reap to find the Sok Yant tattoo master.

Then the engine cut. No roar, no rattle, just a powerless, dead hunk of metal hurtling through the heartlands of Cambodia. I hit the brakes. Must get this thing off the road before a truck flattens me. I stood looking at the engine as cars flew by. Some kind of vapour was rising. Black oil pooled on the tarmac below.

Fucking, shitting bastard. Or some similarly brutal words echoed from the dry, scrubby trees. A truck tore by, stinging my eyes with miniscule stones. If you had been in a passing car you would have seen a single man, crow-black against the sun and yellow dust, dancing a fiendish jig with the purpose, one can only assume, of trying to bring back to life his stationary, oh-so-stationary, motorbike.

The mechanic arrived two hours later, riding my replacement bike and grinning like a maniac. I didn’t return his grin. It was nearly 3pm, which meant I would ride the final hours of my journey to Siem Reap in the dark on one of the most treacherous, poorly-lit roads in Cambodia. The replacement was a similarly large 250cc dirt bike with squishy suspension and a beefy, liquid-cooled engine. The only trouble was that the headlights were significantly smaller than the Baja, which didn’t bode well. Still, nothing for it but to saddle up. I waved to the mechanic, pressed my thumb to the ignition and snapped the small plastic nob like a Sabbuteo figure. I looked at the mechanic in exasperation. He sighed and began unscrewing the ignition box.

It was dark. I aimed the bike between two slightly lighter shades of dark which I took to be the edges of the road. There were no motorbikes. No one was stupid enough to ride in these conditions. There were only enormous trucks with blinding headlights. When separated from the safe confines of modern civilization, it’s amazing how quickly one reverts to atavistic superstition. I had been praying to the god of dogs having narrowly avoided two brutal collisions with road-crossing canines. Just carry on, I repeated, squinting into the blackness as silent sheets of lightning slapped the sky.

The bike choked, coughed and rolled to a stop. I would have known it was running low on petrol if there had been a gauge. But there was no time for rage, just a sense of being worn down and defeated. I was praying again. It must have worked. Emerging from a shack on the opposite side of the road came a smiling family bearing bottles of petrol. They filled it up while rabbiting in Khmer, curious of the foreigner and his giant, broken-down machine.

Thanking them, I sped away. I had barely gone a mile when I realised the petrol was of such inferior quality it might ruin the engine. The bike started up its tuberculotic coughing almost immediately. I twisted my wrist and forced more power into the engine. It wasn’t going to last. Then, a real petrol station emerged from the blackness. Between me and the attendant we drained the sick, village petrol and replaced it.

By the time I arrived in Siem Reap, I was singing the first few lines of Ini Kamozi’s Here Comes the Hotstepper over and over again in an attempt to keep the creeping sense of dread from gnawing at my guts (my cheap earphones had packed in and been cast into the dust somewhere around Kampong Thom). It had been hours driving blind on a road to nowhere. It must have numbed by mind because the fear was that I would never reach Siem Reap and I would be cursed to travel this dark road for eternity.

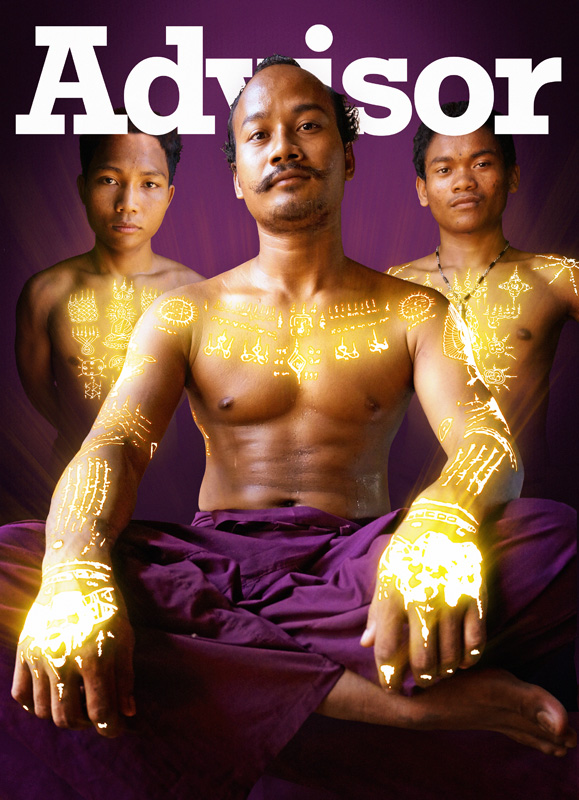

Finding the tattoo master the next morning was comparatively simple. I had already been given his phone number by an American occultist I met at a Phnom Penh meditation group. He was into magic tattoos, acupuncture and studying Taoist grimoires. I called the master and found him outside a large shed among Siem Reap’s quaint, almost Mediterranean backstreets. He wore baggy Thai fishing pants and his muscular body was a mesh of sacred tattoos. His brown skin glowed with sweat in the midday heat. He fixed me with a clear, proud gaze. He had cultivated a moustache that flared up either side of his curled lips like a pantomime villain’s. He took a strand between thumb and forefinger and twirled it.

While it is not difficult to find a tattoo artist who can inscribe mystical symbols on your skin, it is not easy to find someone who practices the whole magical tradition of which tattooing is just one part. “I travelled all around Cambodia,” said the master. “I learned tattooing, mantra and meditation from two main teachers: an old monk and a hermit in Ratanakiri.” He refused to divulge further details. Indeed, he seemed perturbed by my photographs and probing questions. “We want to keep the magic arts secret,” he said.

The ancient art of Sak Yant is a mystical tradition that some say has its roots in pre-Angkorian warrior culture. The symbols used are a mix of Vedic gods and incantations in old Khmer script. When a master tattoos the skin he transfers magical power into the symbols. The most common charms bestow protection, persuasion and sexual magnetism. Take a look at any older Cambodian man, anyone who fought in the war, and you’ll more than likely find faded charms woven into the skin in the belief that it makes the wearer impervious to bullets.

By now, three students had arrived. Fit young men covered in tattoos, some blurry and messy where they had been practicing on each other. “I want to keep the tradition alive,” said Sim So Tum, a young man with a tassled head of hair whose chest bore a line-drawing of the Buddha with spells tumbling out in the eight mystical directions. “My grandfather had the knowledge and power and I am inspired to carry on his work.”

The master pulled out a book of spells that he had created himself, amalgamating the knowledge he had learned on his travels. He and his students pored over the pages. I could have chosen my own design, but it is culturally more appropriate, when dealing with a master of magical arts, to defer to the teacher.

He pulled out the gun and started inking my back. He could have used the traditional bamboo method – where the skin is pieced with a sharpened bamboo needle. But that would have taken longer and been less accurate. He assured me that the power would be the same. “It’s all transferred from the master,” he said.

The return drive back to Phnom Penh was better. In the daylight it’s easier to avoid dogs and see potholes coming. Both shoulders stung with the new tattoos. The symbol for the divine mother was on the left side, the side associated with compassion, while the father symbol was on the right side, associated with wisdom. The archetypal power of the mother and father flowed through my arms and into the bike. I flew home.