In 1997, French curator Christian Caujolle collected 100 ‘identity portraits’ from Tuol Sleng torture centre for an exhibition at annual photography festival Les Rencountres photographiques d’Arles. He placed the exhibition under the theme The Duty of Memory, but photographer Nhem Ein’s unapologetic, even proud, stance prompted speculation on whether the images would have been better placed under the other themes, Forms of Commitment or The Temptations of Power.

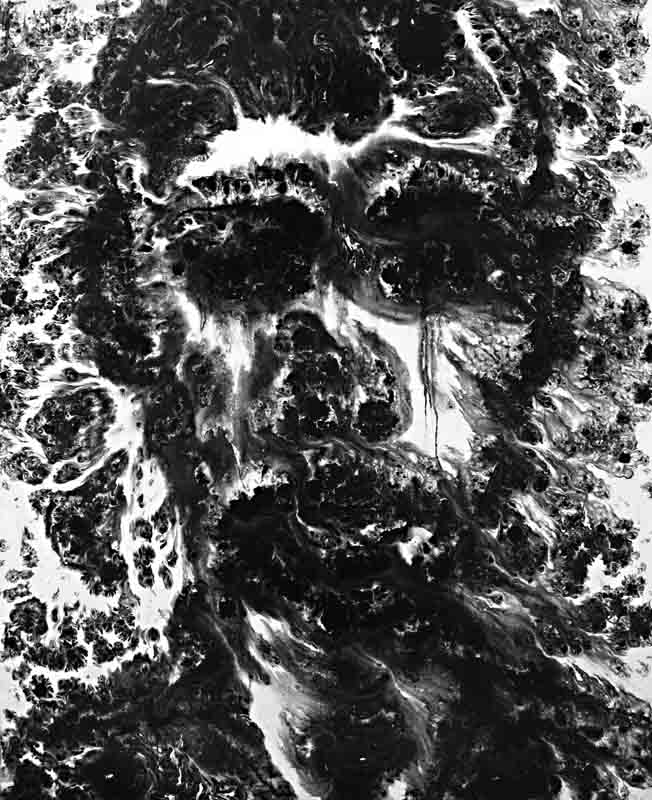

The inclusion of the Tuol Sleng images in the festival, and later in the New York Museum of Modern Art collection, begged another question: are these photographs really art? Twenty-two year old Sin Rithy’s current solo exhibition, What Were They Thinking?, is today reinvigorating that debate. Rithy has enlarged some of the images in his paintings and then effectively destroyed their clarity – a pattern of renewal and destruction that’s affected over a series of 15 paintings.

Rithy’s fundamental concern is that the series works as a memorial to the prisoners at Tuol Sleng. He places immense emphasis on the need to empathise with the suffering of the men, women and children interred in the Khmer Rouge’s notorious interrogation centre, also known as S-21. “I want people to move outside of themselves,” says Rithy, whose unwavering faith in the force of the photographs can be confusing given that his paintings seem vulnerable to the outside effects of aging and weather. “People don’t think about the regime anymore. I hope that the series will help people to think about the feelings of the victims. I chose these images because they are strong. They can communicate.”

The series is divisible by three distinct styles. Only one of these styles – the sunspotted one – can be interpreted as part of the memorialising aspect of his work. The sunspots which blotch some of the paintings are intended, says the artist, to signify the working conditions of prisoners forced to labour in the country’s rice fields.

To make sense of the series as a whole, one would have to acknowledge an overarching conflict between two contradictory forces, which transcends but does not belie the function of evoking empathy. Memorial is one aspect of the series; erasure is the significant other.

What Were They Thinking? evokes the effects of the elements on the physical memorial. Like English Romantic poet Percy Shelley’s most famous short poem Ozymandias, their visages are “half sunk” under the weight of time. Rithy’s paintings simultaneously memorialise and violently erase the horror of S-21.

These paintings have come to Phnom Penh at an interesting point in Cambodian art history. MoMA’s decision to collect the photographs from Tuol Sleng, thereby raising them to the status of art (and subsequently Nhem Ein to the status of artist), contributed to two age-old questions: what constitutes art, and do ethics enter into the practice of art collecting? Rithy’s What Were They Thinking? reminds us of these questions but asks a further one, which can be located in a local, Cambodian debate: is it acceptable to tire of seeing these images?

American essayist Susan Sontag told the world that “images anesthetise”. Pass countless bookstores and book stalls in Phnom Penh and one cannot help but notice the sellers’ tendency to thrust into the foreground publications concerned with the Khmer Rouge. The clash of conflicting forces in Rithy’s series save this body of work from accusations of anesthetising effects. His images are performances: they undo themselves before our eyes. We must seek out the original photograph, only to see it blister and blur around the edges.

Sontag also wrote that “the camera’s rendering of reality must always hide more than it discloses”. What Were They Thinking? plays upon that pattern. Rithy’s paintings remind audiences of the horror of the Khmer Rouge regime, while hiding it behind the anesthetising effects of time.

“This is an old story, but it can be made new,” says Rithy. Arguably, his paintings actually move in the opposite direction. The photograph, forever reproducible and forever made anew, is submitted to the effects of time by transferral to the medium of paint. The painting registers the effects of time and cannot be renewed in its original state by machine or man. What Were They Thinking? makes the old story new by asking these questions of the audience. The images may be tired, but the debate is not.

WHO: Sin Rithy

WHAT: What Were They Thinking? exhibition

WHERE: Romeet Gallery, St. 178

WHEN: July 5 to August 2

WHY: The images may be old, but the debate isn’t