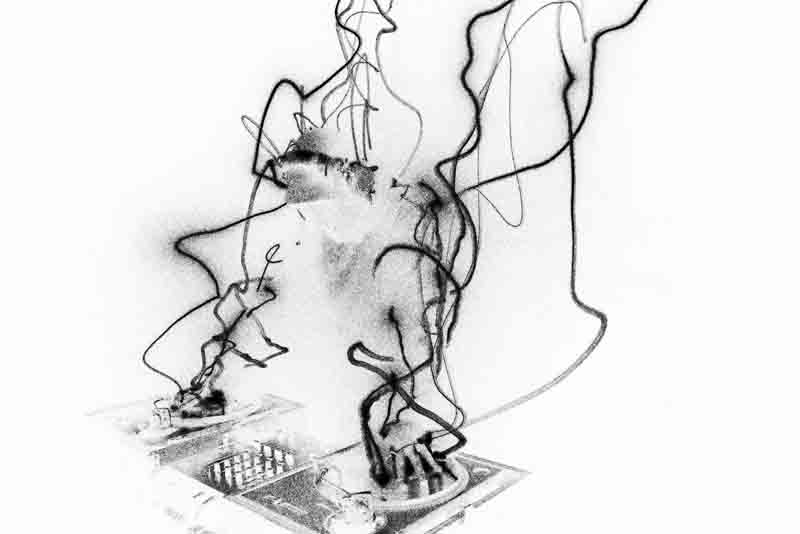

The artist sweeps one arm over a canvas unrolled on the studio floor like a psychedelic welcome mat – a vast technicolour mash-up of lively forms and textures. From the next room, the dull rhythmic thud of bass bins threatens to stir the sticky air. “I will do something connected to his music, to show the rhythm of the sounds, the movement,” she says, nodding towards the door. “I use colours to express emotions and shapes to show the mood. You can see the DJ’s hands moving here, and over there is the sound.” An index finger jabs at enamel that’s been dribbled over acrylic like the zigzag of a hospital heart monitor. “And here you can see the equaliser, like the sounds that come out of the speaker when Warren’s playing.” More pointing, this time at a bright swirl of paint: “This sound here is like a DVD spinning. Each shape expresses an emotion: happiness, excitement…”

Chhan Dina and Warren Daly are daring to tread in some of history’s most well-heeled footsteps. The duo – one a classically trained Cambodian artist; the other a DJ from Ireland – are redefining for the 21st century the complex relationship between sound and vision. They’re in fine company. In Book X of his 4th century BC Republic, Plato describes the ‘music of the spheres’ – the poetic notion that the spinning of the planets generates a sort of celestial harmony. Pythagoras went a step further, musing that these heavenly tones had “a visible equivalent in the colour spectrum”. At the time, only seven planets had been discovered. Two hundred years later Aristotle applied seven numbers to the seven tones of the musical octave, the distinguished foundation of the sound-colour relationship. By the 18th century, Newton’s experiments with prisms seemed to prove its existence through the laws of physics.

And that was just the theorists. Legend has it that Leonardo da Vinci was the first to experiment with the projection of coloured lights, which spurred would-be inventors into trying to make instruments that could spew out coloured lights and sound at the same time. By the time the 20th century rolled around, Alexander Wallace Rimington’s ‘colour piano’ had been seen in public, spawning new oddly named contraptions: Thomas Wilfred’s Clavilux, the Optophonic Piano created by Russian painter Baranoff-Rossiné, and Alexander László’s Sonchromatoscope. Their creators had just one thing in common: they were trying to create a new artistic genre.

Dina and Daly, who met three years ago when he trampled her foot during a swing dance class at Equinox, are 21st century László’s, merging electronic dance music with live instruments and artists and audience participation to create a multisensory experience – a trip without a trip. Led by Daly, who in 2000 co-founded online record label Invisible Agent, they’re building on the work of 1960s San Francisco arts collectives that used disco balls and light projections on smoke to produce trip-like sensations (The Brotherhood of Light, which toured with The Grateful Dead, was inspired by the Beat generation and Ken Kesey’s ‘expansion of consciousness’ Acid Tests).

From acid to aciiiiiiiiiiiiiiiid: enter electronic dance music, 20 years later. It’s had a hard time matching the visual spectacle of screaming singers, windmill-armed guitarists and feral drummers thrashing about on stage. In 1992, British chart show Top Of The Pops hit a record low when The Orb’s ‘performance’ amounted to nothing more than the pair playing chess while their single Blue Room was piped through speakers. With more DJs using software to play mixes ‘live’ on computers, there’s been criticism that the act (some might say art) of physically choosing and mixing records has been replaced with someone simply pressing play and standing back. But as Peter Walker writes in The Independent, “For those acts that can’t get away from being a couple of blokes twiddling knobs – Underworld, The Chemical Brothers, Daft Punk and Orbital – an arms race has ensued to offer fans something to look at while they play. The art of visual entertainment has come a long way, with all of the above using successive albums and tours to test out new on-stage theatrics, from Daft Punk’s pyramid to Underworld’s towering tubes of light and the Chems’ song-specific graphic spectaculars.”

Daly, who has played at Ireland’s famous Temple Bar Music Centre, is well aware of Orbital, famed for their visuals (“The visuals are kind of our lead singer; they’re the lead singer jumping around and pulling faces”, Phil Hartnoll has said). “I was just in time for when Orbital and all the parties were happening in the early ‘90s in Western Europe,” says Daly. “We were putting raves on in fields and getting chased around by the cops.” (Did they ever get caught? “Yes, quite a lot, but let’s not talk about that.”) “You’d have quite a mix there: people DJing; people doing poi; tents, people making food. There was a real community feel to it. You didn’t just come along and watch one guy banging tunes out; there’s a number of different activities going on. We’d make fluoro backdrops, back in the days when fluoro was still cool – the days of glow sticks and Vicks VapoRub.

I started to do visuals at these events in the late ’90s, going out with a camera, making videos of the city and countryside, things happening and people doing things, cutting them all up and splicing it live on screen – putting effects on it, exploding and imploding it, putting colour layers over it; effects that would probably look really cheesy right now, but back then it was like ‘Wow! How’s this guy doing that?’ Now you’ve got software you can just download with all the clips already installed, but we were using two VHS recorders with a cord plugged into the decks.”

In a new series of events at Meta House, December 22 being the soft launch, Daly is fusing pop culture, high culture and low culture by hooking up painters, musicians, graffiti artists, digital artists and DJs into one big psychedelic show. “There will be three DJs playing back to back, each with our own set-up. It’s going to be like a nerd’s dream: a table full of flashing lights and different equipment, but we really want to take it away from where it’s just people looking at us. It’s not about me. I want to play quality tunes, expose some artists and get a buzz going out there in the place. We want to hang canvases up on the walls and get people in the crowd involved; give them a paintbrush.

“We want to mix it up. One example would be Scott Bywater, part of the Cambodian Space Project. He made some electronic tracks and we released them. He played guitar and read poetry over it and some of us have done remixes. When I first heard it, I wasn’t sure – guitars, poetry; am I going to be able to listen to this? Then I heard it and was like ‘Wow, this is ace. This guy really knows what he’s doing.’ He’s using Garage Band on a Mac and asking me all these questions about getting new sequences in there and putting drum beats over them. I thought ‘You’re the singer, you’re the guitarist; you’re the glue on stage for this band and now you’re interested in all these things that DJs and electronic producers use.’ He’s really starting to harness it, too.”

Such experimental fusion is, he says, the future of live electronic music. “There’s a huge lull. You had this massive surge starting in the late ’80s right up to the millennium, when dance music was at its peak. You had big names filling out stadiums – The Prodigy, Leftfield, Massive Attack; commercial, but with underground sounds bubbling up underneath. Then live bands took over for a while and now people like Scott Bywater are saying ‘I’m going to get a laptop.’ And the people with laptops are saying ‘There are guys over there who can play instruments. I’m going to talk to these guys, take some samples and reverse them, and do stuff together.’ We want to make a new form of music.” And it sure beats the hell out of watching two blokes playing chess.

WHO: The sonically and visually open-minded among us

WHAT: Swagger

WHERE: Meta House, #37 Sothearos Blvd

WHEN: 9pm December 22

WHY: It’s the future, man