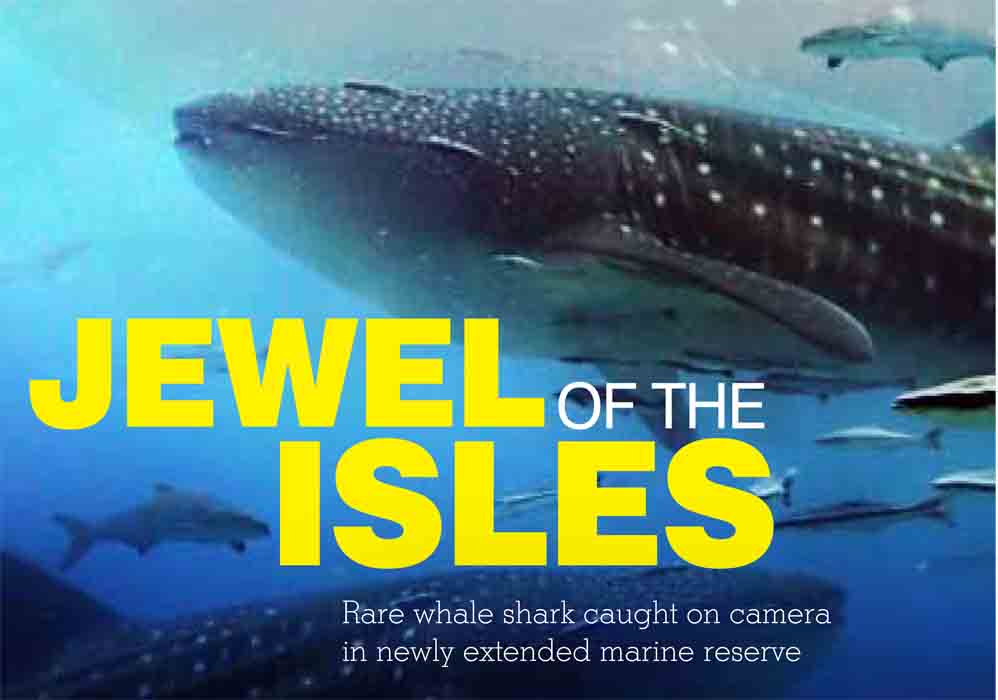

A blunt grey snout swims slowly into view. Following it, at glacial pace, glides a massive flattened head. Shards of sunlight flicker across vast blue-grey flanks that stretch seemingly into infinity. Pale vertical stripes lead up this colossus of the deep to meet two dorsal fins. Then a funny thing happens: the human brain, not designed to process such things, triggers its most primal survival instincts. Pupils shrink to pinpricks. Heart jack-hammers against rib cage…

JAWS!

Because this is a SHARK. A very BIG shark. The sort of behemoth that once prompted cartographers to scrawl across sea charts the ominous words ‘Here be monsters.’ But unlike the razor-toothed, man-eating protagonist of Peter Benchley’s 1974 horror novel, this is a gentle giant.

Rhincodon typus, better known as the whale shark, is the world’s largest fish. Where the great white or carcharodon carcharias sports a bite force of more than 18,000 newtons (4,000lbf), Jaws’ bus-sized cousin is a filter feeder who dines exclusively on plankton. A few weeks ago, off the shores of Cambodia’s first luxury private island, one was caught on camera by the $2,000-a-night resort’s scuba diving instructor – the country’s first recorded sighting of a live specimen since a French photographer spotted one near Koh Prins four years ago.

In the past, whale sharks daring to skirt our coastline haven’t always fared quite so well. In 1973, one weighing 800kg was shot by a soldier in Koh Kapi. In 1998, a 1,000kg example entangled in a gill net was later eaten by locals. A taxidermist was the ultimate recipient of an 1,800kg monster accidentally snared by fishing nets near the Thai border in 2007. And in August of last year, hundreds of people crowded into Sihanoukville’s Leak 1 commune to see a carcass hauled in by fishermen between Koh Del Koh and Koh Tas.

The safe return to Cambodian waters of what British marine biologist Barnaby Olson calls such “charismatic mega fauna” bodes well for the coastline’s future. Although pelagic species of such staggering proportions are rare in these parts, the sighting of a whale shark – known in Khmer as chlarm yak – seems especially auspicious coming, as it does, just as the country’s first private marine conservation area is formally extended to 40 times its original size.

Darting between foreign guests and local dignitaries at the blessing ceremony in the island community of Prek Svay (where, happily for those of us on a more restricted budget, you can stay in a guesthouse on the jetty for $10 a night), a small girl diligently gathers up empty drinks cans. “There she goes! She’s a little entrepreneur, that one. Next thing you know, she’ll be building a luxury resort…” Dr Wayne McCallum, an affable New Zealander, is the pencil-moustachioed head of Song Saa resort’s conservation and community programme. His task today, here in the Koh Rong archipelago, is to help cut the ribbon as the reserve set up in 2006 officially swells from 5.5ha to 219ha. Dabbing his face free of chili-induced sweat, McCallum offers his young charge another empty can.

This is the very essence of what Song Saa’s philanthropic arm, Footprints, is trying to encapsulate: ‘Luxury that treads lightly,’ to borrow from the official pamphlet. A full no-take zone, Cambodia’s first and only, extends 200 metres out from the shore of each island. Song Saa’s underwater lab, another national first, allows the marine team to monitor everything from reef generation to the impacts of climate change. One hundred artificial reef structures have been built. Borrowing once more from Song Saa’s tantalising literature, ‘While guests can snorkel and swim to visit the reefs, or view one on dry land at our Discovery Centre, those who occupy an overwater villa can view the reef through the see-through floor portion of their accommodation. Better than television, fish can be seen moving in and out of the artificial reefs without the need to get your feet wet.’

There’s more. The Blue Carbon Project gives guests the option of offsetting their footprints, while more than half the land has been deliberately left undeveloped as a nature reserve. And more: island community projects funded directly by profits from the resort now include everything from organic farming and aquaculture to solid waste management and midwifery.

“The general consensus is that things have improved since Song Saa was built,” says Nick Chandler, director of sales and marketing. “The owners, Rory and Melita Hunter, first visited here eight or nine years ago and it was a completely different place. They fell in love with the region and have been really conscious about ensuring this isn’t a big obnoxious luxury resort that just gets dropped in next to this little village. That’s why you see from the design perspective that Song Saa doesn’t stand out from 20 miles away: it’s designed to look like the surrounding fishing villages and blend into the landscape, while still providing the kind of amenities someone expects for $2,000 a night.”

Barnaby nods. “The response has been a very good one, partly because this island had a very strong sense of community to begin with. We’ve made a real effort to do the work in an appropriate manner, addressing the right people at the right time, moving things nice and slowly but making sure each of our projects has the legs to look after itself. We don’t just come in and throw money at a problem and expect it to work. We engage the community; explain why we’re doing things, how we’re doing them and what the benefits will be. Really build up a good understanding of what we’re trying to do. Two local guys do all of our community work for us. Having locals talk to locals: it doesn’t matter where you are in the world, that’s the way to go.”

Part of the Song Saa team for two-and-a-half years, Barnaby is a witness to how the ecosystem is changing as a result of their efforts to protect the archipelago’s giant clams, turtles and sea horses against the use of bottom trawling, poisons and explosives in fishing. “Certainly around Song Saa you can visibly notice more fish and more big fish, which is the important one because bigger fish produce more juveniles and the juveniles than add to the ecosystem. It’s important to be seeing these big snapper and barracuda and we’re seeing them here a lot more.

“It’s a very diverse system. We get slower-growing corals here; they save up their energy and put it into structural strength and energy reserves. In places like the Great Barrier Reef in Australia you get faster-growing coral, but it’s more boom and bust: it grows very quickly then along comes the next storm and flattens it. The corals we have here are known as boulder corals because of their shape – they look like big lumps of rock. They’re a lot stronger and have more energy reserves, which allows them to get through periods when the water climate isn’t so great and they’re not getting as much sunlight as they need.

“If you can protect a coral reef from all the impacts you can, whether it’s overfishing, damaging fishing techniques or uncontrolled anchoring of boats, then when that big ugly global impact comes along, whether it’s rising sea temperatures or pollution from another source, you’ve given it the best fighting chance you can. It’s the same with a human: if you’re stressed and tired and rundown and not eating well, of course you’re going to get that cold and that cold is going to put you to the floor, but if you’re healthy in every other way, that cold comes along and you can fight it off and stay healthy.”

But such eulogising isn’t restricted to Song Saa staff. Guests, many of whom are impossibly famous (our hosts are too discrete to name names but note that Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie were turned down when they tried to book the entire resort for Christmas just three weeks in advance), are getting in on the act, too. “The people who come to Cambodia have done so as a conscious decision, so automatically they’re a little bit different,” says Wayne. “Obviously not everyone comes with the same philosophy, but you only need a few. Some of the people we get here – we can’t say who they are – they’re pretty amazing. Someone left a $2,000 tip a while ago, which we gave straight to Life Options: no board meetings; no funding proposals, none of that crap.”

Whale sharks, sea horses and turtles: yours for $2,000 a night (or $10 – up to you).

WHO: Adventurous travellers with sound ethics

WHAT: Cambodia’s newly extended first private marine reserve

WHERE: Song Saa and Prek Svay, the Koh Rong archipelago

WHEN: Now

WHY: To live off the sea, we must understand and respect it