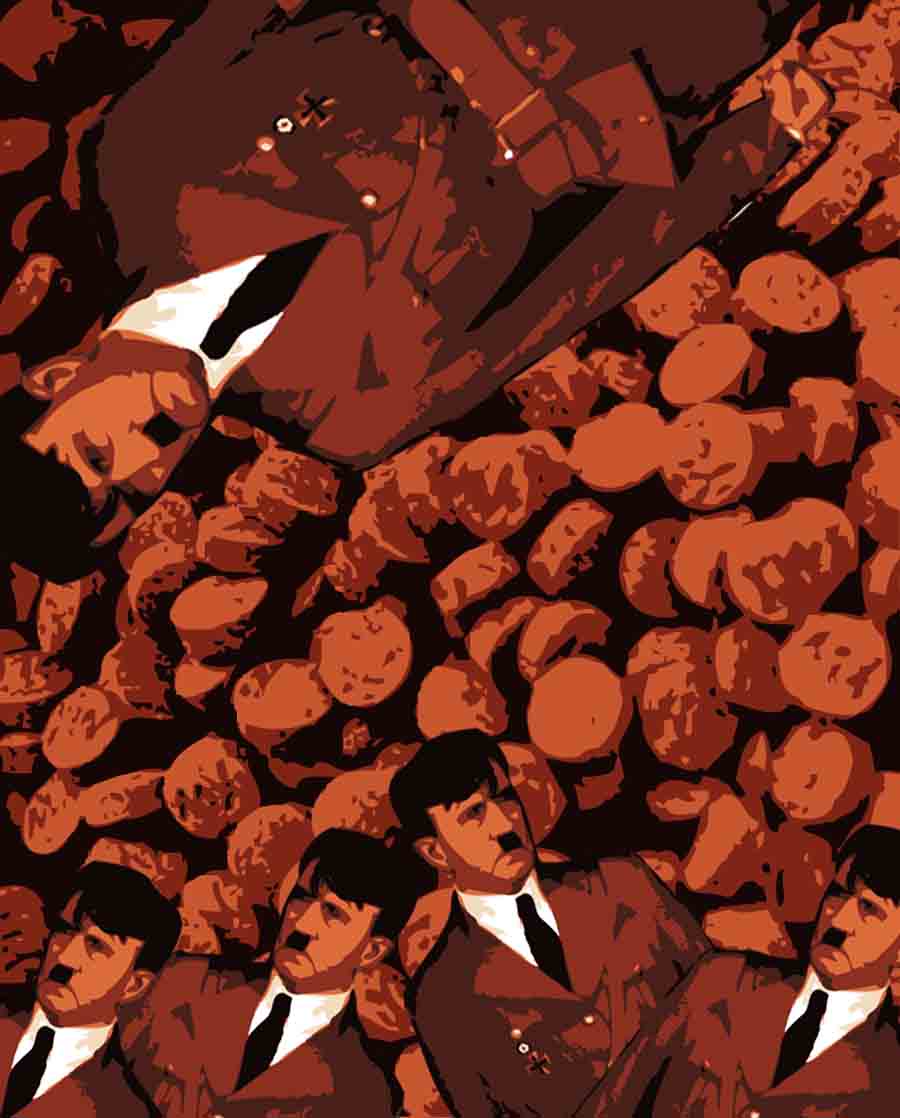

Adolf Hitler ingested it daily in a cocktail of more than 80 drugs, turning him from an egomaniac into a sadistic mass murderer. Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg and the Beatles warned against it during the late ’60s as flower power gave way to cutthroat consumerism. And in 2003 the US Air Force was forced to defend it after two pilots under its influence dropped a bomb near Kandahar in Afghanistan, killing four Canadian soldiers.

Methamphetamine – known variously on the streets as speed, meth, crystal meth, ice, shards, shabu, glass, jib, crank, batu, tweak, rock and tina – is today considered by many to rank among the world’s most dangerous drugs. But it wasn’t always so. First synthesised from ephedrine by Japanese chemist Nagai Nagayoshi in 1893, this powerful psychostimulant was used extensively by both German and Allied forces during World War II as a performance enhancer. By the 1950s, under the name Obetrol, it was being handed out by American pharmacists as treatment for obesity and soon became a popular diet pill. It wasn’t until the 1970s, as its addictive properties began to be documented, that meth – the subject of two very different documentaries screening at Meta House this month: Hitler’s Drug and Asia’s Speed Trap – was finally declared a controlled substance.

In the late 1930s, as the Axis powers were squaring off against the West and the Soviet Union, the thought couldn’t have been further from anyone’s mind. Letters by German post-war writer and Nobel prize-winner Heinrich Böll, published by Der Spiegel for the first time last year, include increasingly desperate pleas to his family to send more Pervitin – the name under which meth was packaged as an ‘alertness aid’ and sold to the frontline.

Another letter, penned in 1942 by a Nazi medical officer, says he used the Class A drug after troops were surrounded by Russians and trying to escape in sub-zero temperatures: “I decided to give them Pervitin as they began to lie down in the snow wanting to die,” the officer writes. “After half an hour the men began spontaneously reporting that they felt better. They began marching in orderly fashion again, their spirits improved and they became more alert.”

But this ‘miracle pill’ also came with horrendous side-effects, among them dizziness, depression and hallucinations. Some soldiers died of heart failure; others shot themselves in a psychotic haze. Former Reich Health Leader Leonardo Conti warned of the dangers in a speech to the medical association in Berlin City Hall: “Whoever wants to eliminate fatigue with Pervitin can be sure that the collapse of its performance must one day come… It should not be applied to any state of fatigue, which can be compensated for in reality only through sleep. This must be readily apparent to us as physicians.”

To some physicians, perhaps, but apparently not to Hitler’s. Dr Theodore Morell, dubbed the ‘Reichmaster of injections’ by the Nazis and himself obese, daily prescribed to the 5’8” Fuhrer – a hypochondriac who suffered from manic depression, Parkinson’s, deformed genitals and almost no sex drive – a lethal medley of everything from meth, morphine and barbiturates to bull’s semen, rat poison and the oil used to clean guns (unsurprisingly, he also suffered from uncontrollable flatulence). These revelations finally came to light in 2012, when a select few of Hitler’s medical records went under the hammer for more than $2,000 a piece.

One psychiatrist, Professor Nassir Ghaemi, has since suggested that Hitler’s unfortunate habit exacerbated the Nazi leader’s manic depression, triggering a behavioural shift that ultimately resulted in the deaths of millions. “It’s not whether Hitler was an amphetamine addict or not; it’s that Hitler had bipolar disorder and amphetamines made it worse,” he says in National Geographic documentary Nazi Underworld: Hitler’s Drug Use Revealed (High Hitler, by the History Channel, is also worth a watch). “That is the issue. That has never been described before and that would explain a lot why Hitler changed in the late 1930s and the 1940s.”

Within a decade, however, Japanese workers were being given methamphetamine by their bosses to boost productivity. At the same time the Beat generation in the US was casting off marijuana and embracing meth, most notably in the form of Benzedrine or ‘bennies’ – the source of Jack Kerouac’s legendary stamina (he allegedly wrote On The Road in one sitting). The godfather of Gonzo journalism, US author Hunter S Thompson, makes frequent references to it, as in his author’s note in Fear And Loathing On The Campaign Trail ’72:

“One afternoon about three days ago [the publishers] showed up at my door with no warning, and loaded about forty pounds of supplies into the room: two cases of Mexican beer, four quarts of gin, a dozen grapefruits, and enough speed to alter the outcome of six Super Bowls… Meanwhile, with the final chapter still unwritten and the presses scheduled to start rolling in twenty-four hours… unless somebody shows up pretty soon with extremely powerful speed, there might not be a final chapter. About four fingers of king-hell Crank would do the trick, but I am not optimistic.”

Even Paul Erdos, one of the greatest mathematicians in human history, was a tweaker. Having experimented with amphetamine early in his career, a depressed Erdos began taking that and methylphenidate every day at the age of 58 following the death of his mother. Concerned, a friend bet him $500 that he couldn’t go a month without the drug. Erdos won the bet, but complained bitterly: “You’ve showed me I’m not an addict, but I didn’t get any work done. I’d get up in the morning and stare at a blank piece of paper. I’d have no ideas, just like an ordinary person. You’ve set mathematics back a month.” He promptly went back to taking amphetamine, every day, until he finally died at the age of 83.

Where heroin was once the most profitable drug produced in the remote labs of the Golden Triangle, where the borders of Burma, Thailand and Laos collide, a complex sequence of political events has spurred the rise of what is now a multibillion-dollar meth industry here in Southeast Asia (worth $8.5bn last year, according to the UN’s Office on Drugs and Crime). First, the Communist Party of Burma imploded in a 1989 coup. Chinese funding then dried up and the United Wa State Army was born. After years of insurgency, these rebels signed a peace deal with the ruling military junta in which, according to Jane’s Intelligence Review, the business opportunities involved in a shift from heroin production to methamphetamine were made ‘implicit’.

At the same time in Thailand, another strain of meth was surfacing: yama (‘horse medicine’), popular among long-distance truck drivers and students alike. When the police saw its effects, they coined a new name for the little vanilla-scented pink pills: yaba (‘madness medicine’). Easier to make than heroin and less subject to the vagaries of the weather, this potent stimulant was, as Jane’s notes, “far better suited to markets in a region embarking on rapid economic growth”.

Today, in Southeast Asia alone, there are estimated to be more than three million meth addicts and their numbers are rising. Each addict risks psychosis, rhabdomyolysis, cerebral haemorrhage and even brain damage. Why so enduring, when the evils of such poisons are painfully apparent? Why the inexorable rise to ubiquity of methamphetamine, which, unlike amphetamine, is neurotoxic to us humans? As National Geographic notes in another documentary, The Most Dangerous Drug In The World: “Pressure to compete has created a generation of Thai meth addicts.”

“It gives me energy and makes me feel like I have to be doing something all the time; I can’t stay still,” one Thai housepainter tells the camera. “I can work for two days and two nights straight without stopping. If I don’t have the drug, my muscles feel weak and I can’t do anything. I don’t have any energy so I have to use more yaba and then I can keep working.” Sex workers echo his sentiment: more energy equals more boyfriends equals more money. And on it goes.

But when in 2003, under the orders of then Prime Minister Thaksin Shinwatra, Thai soldiers began shooting suspected drug addicts on sight, the UWSA realised it was time to expand their market (in Thailand, as documented by BBC One’s MacIntyre Investigates a year earlier, dealers caught with small amounts are sentenced to death; erratic drug behaviour in the streets can earn offenders summary execution).

In May of this year, when the UN released its annual Global Synthetic Drugs Assessment, it noted that Asia has become the world’s biggest supplier of amphetamine-type stimulants, with seizures increasingly being traced back to labs in Cambodia. “In 2006, the heroin supply temporarily dried up in Cambodia because of Thaksin’s war on drugs in northern Thailand,” David Harding, a technical adviser with Friends International, told a local newspaper at the time. “That was the beginning of an accelerated rise in the supply and consumption of crystal methamphetamine… a glut of crystal meth that had not been affected by the breakdown of traditional supply routes suggested that it was home-grown.”

Today, more than 90% of Cambodia’s drug users are battling meth addiction at a time when authorities across Asia are failing to address the threat it represents – a paradigm which, when viewed in light of the drug’s historical context, threatens to unravel society itself; a paradigm captured fairly well in the second of Meta House’s documentaries, Asia’s Speed Trap by Al Jazeera, but woefully fumbled in Hitler’s Drug, filmed among a small group of meth users in a Poipet shed by Alessandro Molatore.

Molatore, perhaps in a quest for rawness, spends the 11 minutes of his film with the lens focused almost unwaveringly on one individual, yet despite this we learn almost nothing of why he does what he does; whether he is aware of the possible consequences, not least for his wife and young son; what first prompted him to inhale the aromatic smoke from a line of crushed pills on a small piece of folded tin foil balanced above a lighter. No one challenges him when he tells the camera in halting English: “We don’t steal, we don’t rob, we don’t kidnap; the money we use for buying drugs comes from good jobs… We are not black people. We are not mafia…”

But where Hitler’s Drug manages to disappoint despite the overwhelming allure of its title, Asia’s Speed Trap whets the appetite for information and analysis – hence the mention of several other documentaries worth watching online. Here, the directors move from undercover cops to police laboratories to an Army-run ‘rehabilitation centre’, one of 86 dotted across Thailand, where treatment amounts to ‘exercise – and lots of it’, along with advice such as ‘Please keep eating fish sauce, because when you take drugs you lose calcium. Fish sauce replaces calcium and makes you sweat. The drugs will come out with your sweat.’ (Don’t try this at home – The Ed.) Relapse rates across Asia are ‘shockingly high’, says the World Health Organisation: between 60 and 95% of people who go through compulsory treatment fall off the wagon. Only Malaysia, as detailed in Asia’s Speed Trap, is now pioneering a new type of treatment: voluntary ‘cure & care clinics’.

Bundit Sripen, a second-time offender with a wiry frame; tattooed face; billowing football shorts, flip flops and a big yellow Boy Scout-style scarf, grins: “I first smoked yaba in my early 20s. I saw my friend using it and wondered how it would feel, so I asked my friend to get me some. I love its smell. It smells great! After smoking, I have the energy to do many things. The bad part is I can’t sleep. I stay up for days and start getting paranoid. I hear voices. I can’t eat like I used to…”

WHO: Meth heads and tweakers

WHAT: Hitler’s Drug and Asia’s Speed Trap screenings

WHERE: Meta House, #37 Sothearos Blvd.

WHEN: 7pm July 22

WHY: The real Breaking Bad