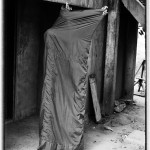

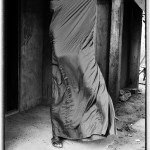

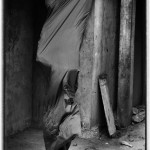

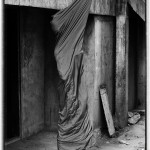

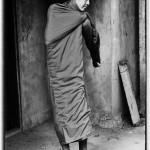

Before monks prepare themselves to leave their pagodas and venture out into the city, a remarkable – almost dance-like – performance unfolds with steady, practiced body movements. Quickly and securely, the monks cocoon themselves within their robes and emerge a couple of seconds later, looking the part: multilayered and beautiful, timeless, expressing an outer worldliness kind of dignity. Photographer Michael Klinkhamer was welcomed into the Areyaksat pagoda in Phnom Penh to get up close while a young monk was getting himself all wrapped up, ready to step out into the material world.

…..

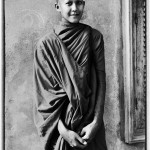

You see them everywhere: Buddhist monks striding along solo, or together in colourful groups through the busy streets. From early in the mornings, collecting donations and food, until later in the day before sunset when they find their way around town for some additional study or teaching, or spend some time relaxing along the Phnom Penh riverside.

The flowing robes worn by these ubiquitous monks – in saffron shades ranging from bright yellow to blazing orange to deep, dark red paprika or a stylish maroon – are part of a 2,500-year-old tradition that dates back to the days of Buddha himself, whose very first monks wore robes patched together from rags. As the number of his disciples grew, Buddha devised a few regulations about their robes, all of which were recorded into the Vinayap-pitaka, one of three Buddhist scriptures that together comprise the Tripitaka (its primary subject matter: monastic rules for monks and nuns).

In those early beginnings, Buddha instructed his disciples to scavenge for rags from rubbish heaps; to find useless cloth that had been chewed by rats or oxen, scorched by fire, soiled by childbirth or menstrual blood, or used as a shroud to wrap the dead before cremation.

Any part of the cloth that was unusable was trimmed away, with the remaining cloth ‘purified’ by being boiled and dyed. Bark, flowers, leaves and spices such as turmeric or saffron gave the cloth its distinctive saffron colour.

Nowadays, ‘modern’ monks can simply visit the local markets, where robes are for sale for about $25. They are free to choose a shade that fits their mood or desire for personal expression. There is no real ranking, rule or status that dictates the kind of colour they wear. Young novices are typically dressed in yellow or bright orange robes, while a pagoda master monk might choose a more modest shade such as cumin or saffron (in all, there are six colours to choose from). During the annual water festival celebrations here in Cambodia, many are gifted new robes by their local communities.

DID YOU KNOW?

- A Theravada Buddhist robe is called sbang cheypor in Khmer

- The sbang is used to cover the upper legs; the cheypor is used to cover the torso

- The krang cheypor is the part that allows the right shoulder and arm to be uncovered

- Buddha designed a piece of cloth called the antaravaska, measuring about six feet by nine feet, that wraps around the torso, sometimes folded and draped over the shoulder

- According to the Vinaya-pitaka, Buddha asked his chief attendant Ananda to design a rice paddy pattern for the robes, so Ananda sewed strips of cloth representing rice paddies into a pattern separated by narrower strips to represent paths or waterways

- To this day, many of the garments worn by monks are made of strips of cloth sewn together in this pattern, often a five-column pattern of strips, or sometimes seven or nine strips

- In the Zen tradition, the pattern is said to represent a ‘formless field of benefaction’; it might also be thought of as a mandala representing the world

- An under dress, these days held together with modern zippers with a couple of handy pouches for personal belongings, is called a hangsak and is mostly worn during work activities in the pagoda

- Khlum cheypor is the way to dress when leaving the pagoda and covers all upper body parts, including arms and hands

- An additional cloth, ben bat, is used to cover the body while collecting daily food offerings from private homes or local businesses around town

- A wide ribbon, called wathapun, ties the whole outfit tight

- To hold the cheypor together, monks use a woven rope belt, called ottarkhot

- In cold weather or strong sunshine, a sangadey – folded many times – is draped over the bare shoulder by way of protection