Rules, as we all know, were made to be broken. Especially rules that are outdated, outmoded and outrageous. Surely no one ever truly intended men and women to live under the yoke of such despotism as the Indonesian decree that anyone caught masturbating can be decapitated? Or the law that in France one cannot name a pet pig Napoleon? Or the one where, in the UK, a pregnant woman can relieve herself in a place of her choosing, even in a policeman’s helmet? Actually sir, let that particular law of the land remain!

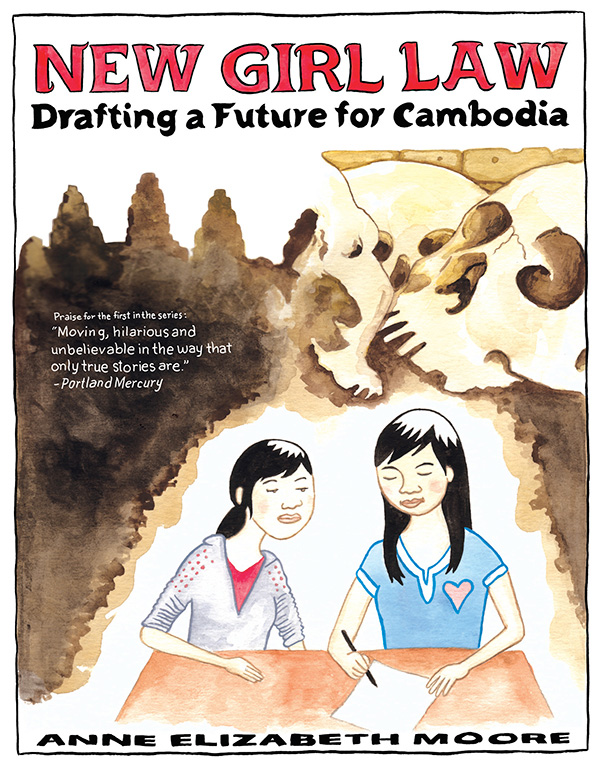

But the point is that there comes a time in every nation’s evolution when its rules and laws should be reassessed. Picked apart and re-made, if not broken. This is essentially the task that author, Fulbright scholar and grumpy feminist punk Anne Elizabeth Moore set a group of young Cambodian women when she asked them to rewrite the Chbap Srey (‘Women’s Law’). The result of this complicated, complex and at times completely hilarious exercise is New Girl Law, published in March: Moore’s docu-memoir of how 32 Cambodian girls imagined a better world and a better set of rules for generations of women to come.

For those not versed in its teachings, the Chbap Srey is quite simply Cambodia’s codification of idealised femininity. Literally translated as ‘Women’s Law’, the Chbap lays out an age-old set of behavioural principles by which good girls should live: obedience, inferiority, pliability, passivity. Sound familiar? Moore is quick to point out that these “virtues” are hardly unknown to women worldwide; all Cambodia did was inscribe them into an actual factual rulebook instead of inculcating ladies by even more sinister means. Taylor Swift’s lyrics, for example.

So why, I hear you right-on sisters wail, why bother to rewrite the Chbap Srey at all if it’s as bad as Taylor Swift? Why not just chuck the old law out wholesale and start the feminist revolution? Why would a riot grrrl like Moore fanny around writing a book about making sexism a little bit more palatable?

The answer in fact lies in one of Moore’s greatest strengths: her refusal to bring a moralistic sense of rectitude to bear on Cambodia. Hailing from a punk-feminist background, she does not adopt the stance that the West is some sort of idyll when it comes to women’s rights. New Girl Law is structured as a series of collaborative debates between Moore and her young female charges on how best to strengthen women socially and legislatively in the real world, Cambodia today. The author is fully aware of her home nation’s shortcomings, historical and contemporaneous, which enables her to steer clear of the NGO saviour narrative. Nicholas Kristof and Somaly Mam, take a lesson.

Of course, this refusal to moralise to the 32 women whom she challenged to rewrite the Chbap Srey means that Moore had to compromise. The 20 resultant ‘Girl Laws’ contain some edicts which read a trifle oddly to Western feminists: the seemingly androcentric “Girls should be brave enough to make eye contact with and speak to boys,” or the passive-sounding “Be patient.”

Musing on patience, Moore told the Phnom Penh Post: “I actually think that my body of work and history of being in the world presents a pretty clear view that patience is always bad and so when it was sort of presented to me as not only the most important thing but as the foundational thing from which we will build this project together, I was sort of like: ‘Oh, okay.’”

These may not sound like the words of a woman in the throes of making big compromises, but bear in mind that for Moore they are probably a big deal. She is after all an author capable of writing “men greeted each other loudly in congratulations, probably just for being men, I didn’t know”. Now, the ladies of The Advisor are not averse to a spot of feminist bovver ourselves from time to time, but that stuff smacks of the First Wave rather hard.

These are tiny little niggles, though. New Girl Law is, get ready for it, an important book. It’s important not just because it’s funny and warm and thought-provoking, but because through it you hear the voices of young women in the developing world. Advocating for themselves, asking for their rights, breaking the rules. These are voices that are normally silenced. The scope of New Girl Law’s success can be gleaned by the fact that it ran up against four years worth of publication and distribution problems in the US: “modes of censorship”, in Moore’s terms. If The Man tried to censor it, you punks know it must be good.

WHO: Anne Elizabeth Moore and 32 future women leaders

WHAT: New Girl Law: Drafting a Future for Cambodia

WHERE: Bookshops across Cambodia

WHEN: Now

WHY: Rules were made for breaking. Especially sexist ones (this is not a joke)