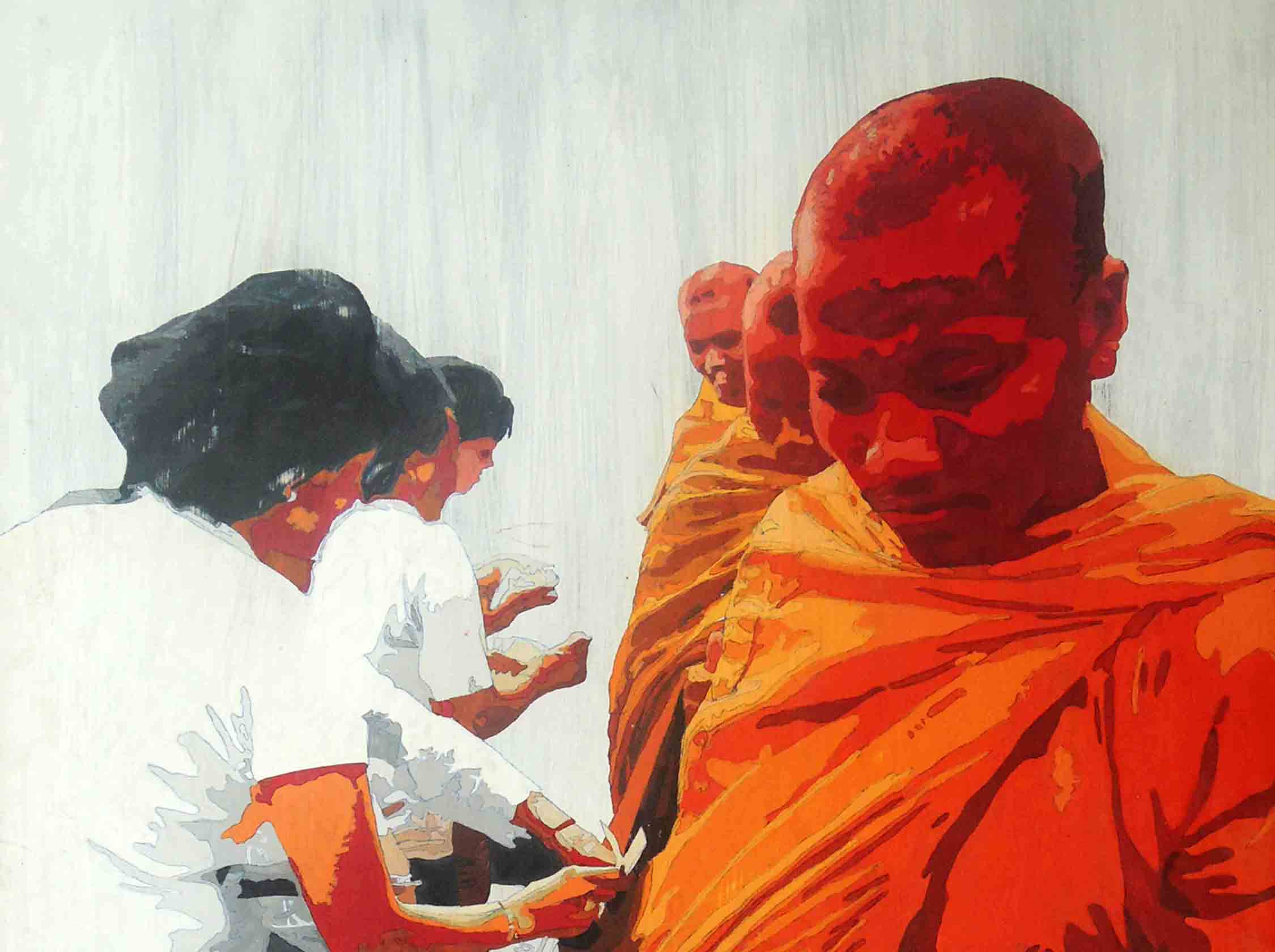

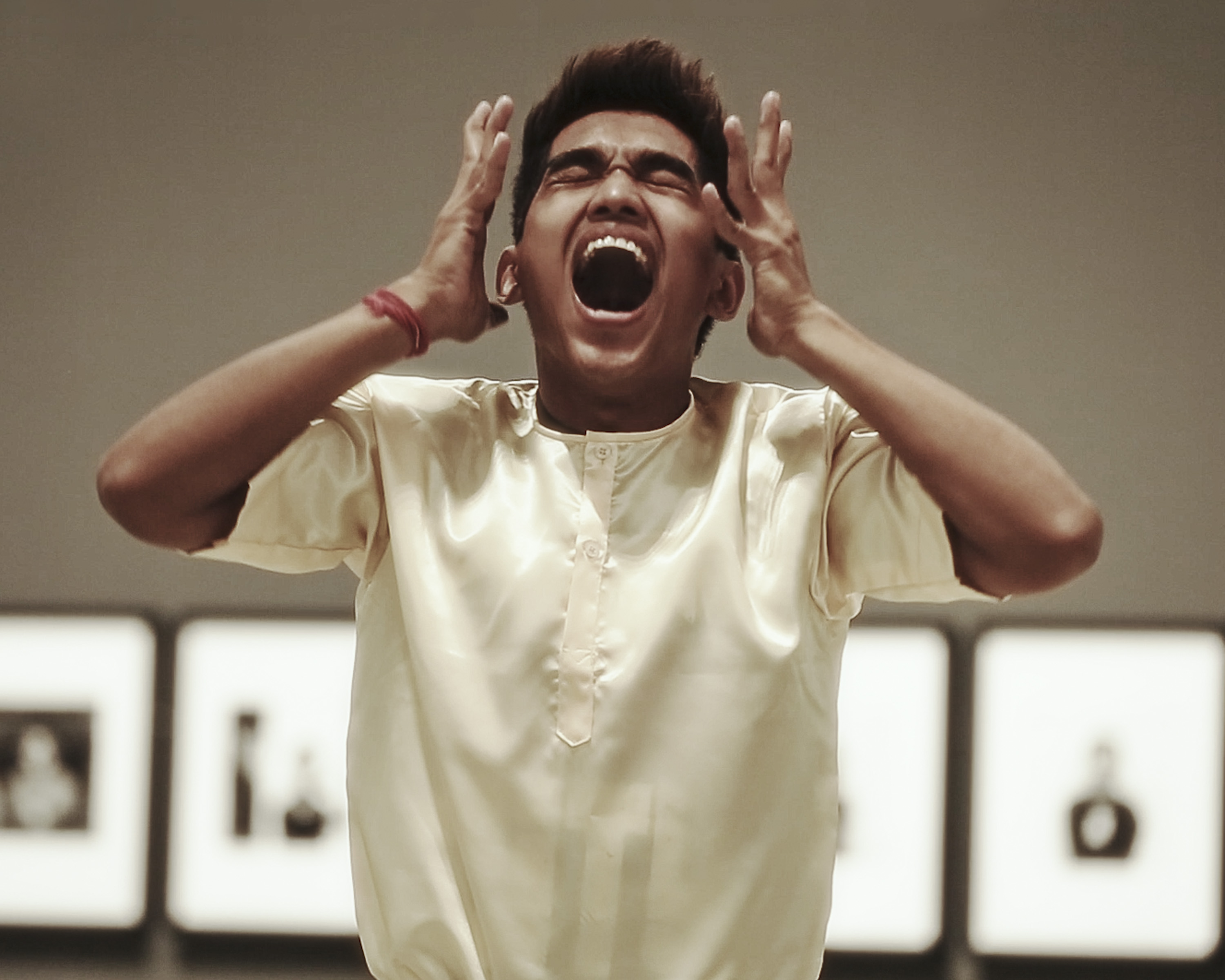

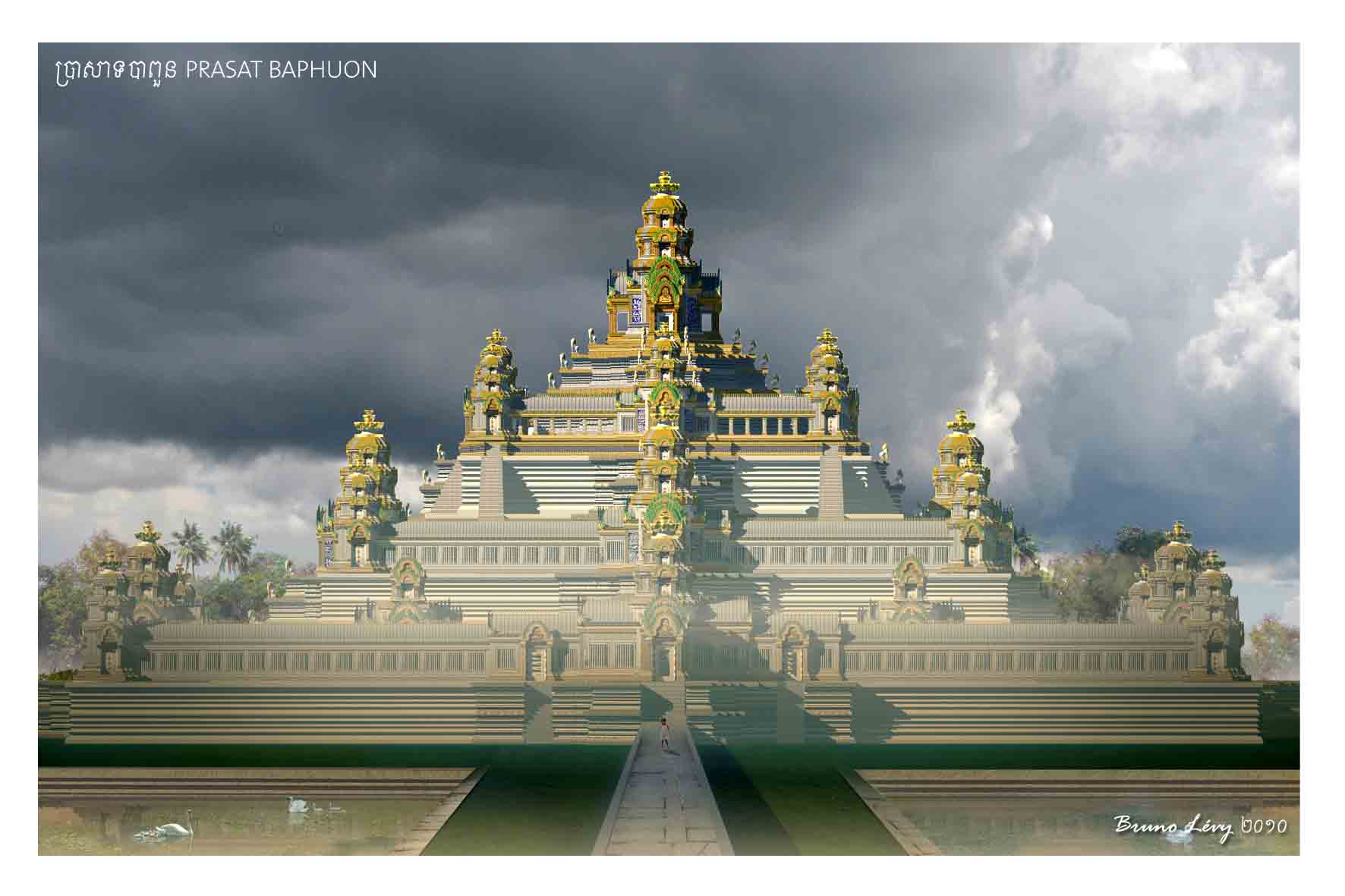

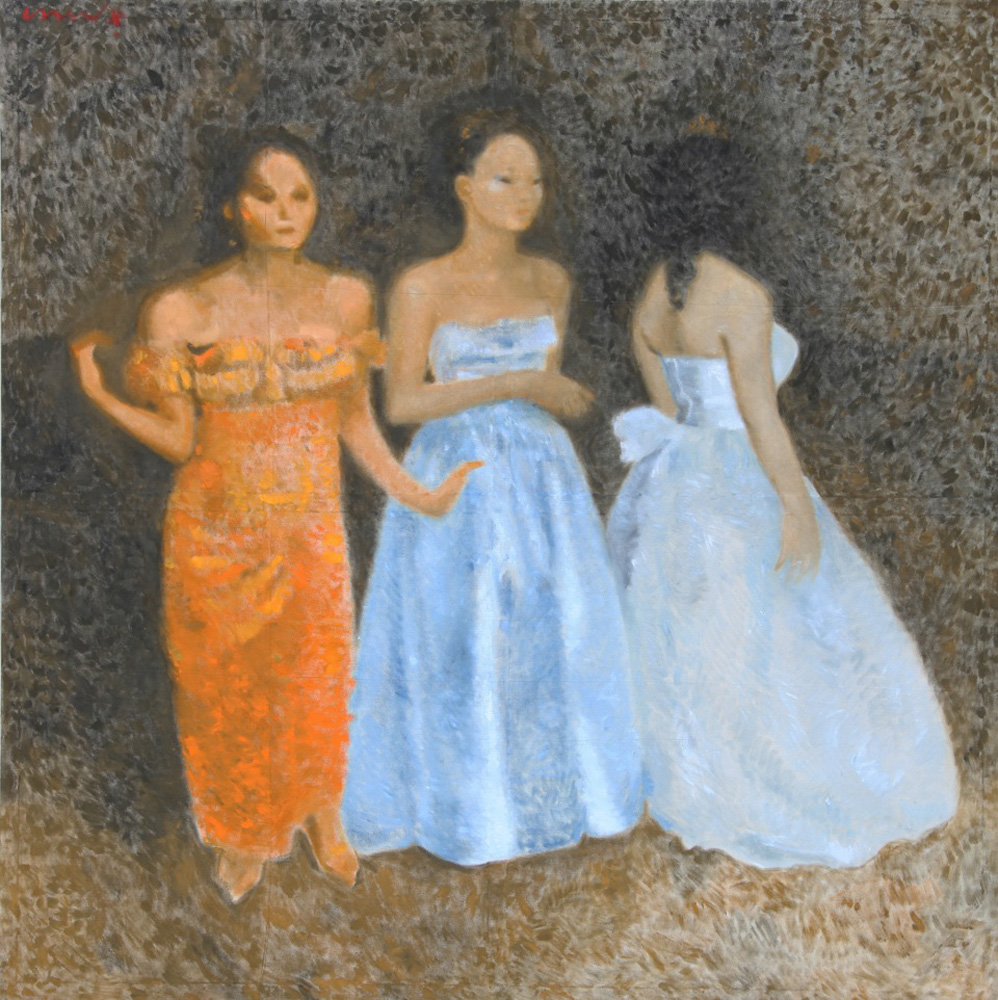

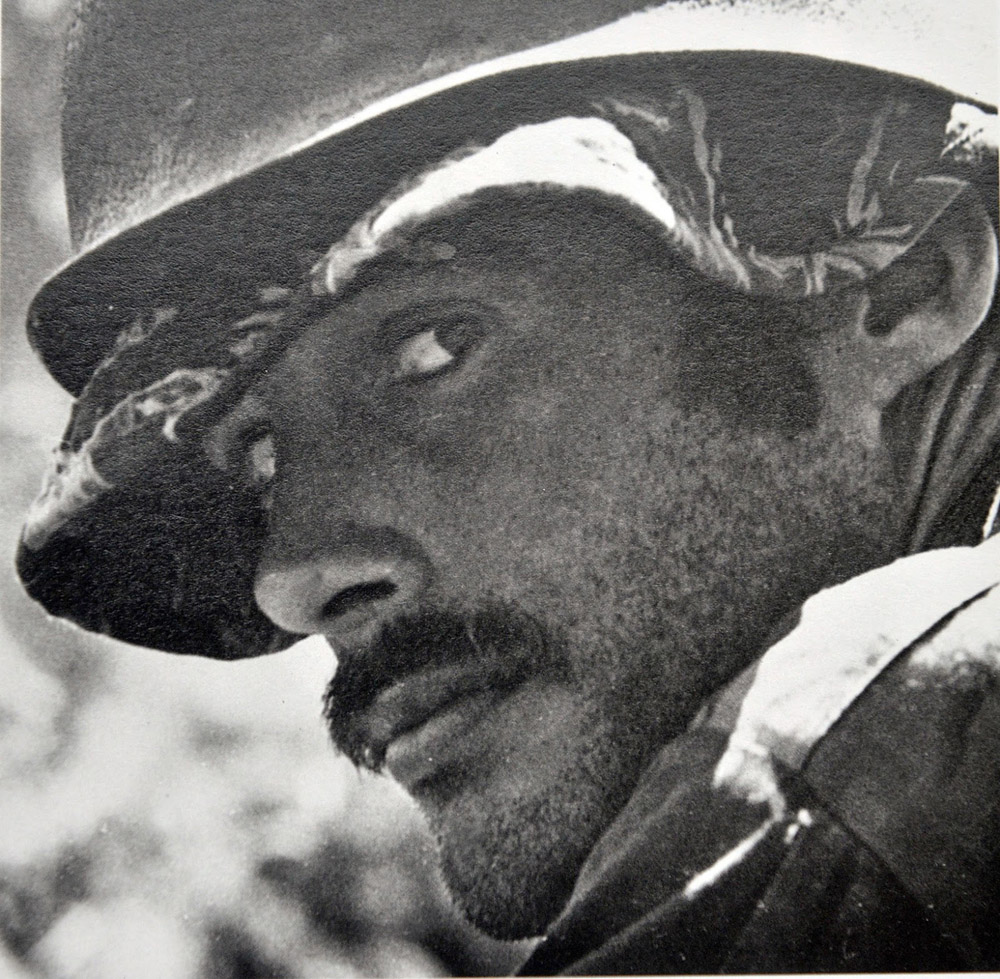

Siem Reap is the kind of place where empires rise and fall. It may not look like much sometimes, with its streets littered with backpackers and, well, litter, but Siem Reap has seen it all: the defeat of the Siam hordes (from which the modern-day town derives its name); the glory days and the dog days of the Angkor Kingdom; Siamese invasion; French colonial administration, followed by civil war and lean years for the town. You can say this for Siem Reap: it’s never dull. Now, as Cambodia dusts itself down following the 20th century, the town is still at the heart of the nation’s changes. Nominally home to less than 900,000 people, Siem Reap welcomes more than two million tourist visitors every year. The ever-increasing number of luxury and not-so-luxury developments in and around the French colonial streets speak to the rapidity of change in the region. Tourism may be booming, but it’s still business as usual for many of Siem Reap’s inhabitants: cow-herds mooch by the river and monks collect offerings at dawn. The co-existence of ancient and modern ways of life is apparent all over the country, but nowhere more so than here. When artist Lim Muy Theam returned to Cambodia from France in 1998, he found the town – and the nation overall – on the brink of yet more change. Describing Siem Reap as being in “permanent evolution”, Theam made it part of his mission to capture and preserve disappearing sights and traditions. Situations, Theam’s new exhibition at the McDermott Gallery in Siem Reap, captures the traditional everyday activities of the city’s streets before they vanish beneath the torrent of tourism. A series of portraits, the lacquer polychrome paintings show ordinary people going about ordinary rural tasks – farming, hawking, herding – set against greyscale urban backdrops. The figures in the foreground look outwards towards the unknown future of the Kingdom while the background recedes in giddy perspective, as if the past can’t disappear fast enough. While they focus on normal everyday life, Theam’s recent works also reference the nightmares of the Khmer Rouge era, a subject with which the artist is familiar. Born in Takeo province, Theam was nine years old when Pol Pot’s regime fell and he fled to France as a refugee. Despite making a success of his creative career in France – studying painting for a year at Paris’s Ecole des Beaux Arts and Interior Design from the Ecole Boulle then working in design industries – Theam nonetheless felt compelled to return to his birth country and “take part in the rebuilding of a country ravaged by decades of war”. A previous series of paintings, also in lacquer polychrome, were based on photographs on show at the Toul Sleng Genocide Museum. These works, which showed red figures against historical backdrops, intimated that while time passes and places change, the plight of the Cambodian poor rarely improves. “The background changes,” Theam explained at the time. “Sometimes it’s during the Khmer Rouge or the Vietnamese periods… the people remain the same. The government never takes care of the poor people.”

WHO: Lim Muy Theam

WHAT: Situations art exhibition

WHERE: McDermott Gallery, Old Market, Siem Reap

WHEN: Until February 28

WHY: The times, they are a-changin’