“My idea is to document and photograph memories. If people don’t like it I don’t mind. I think a lot of my images cannot sell to the public. But I don’t care, I just want to photograph.”

It seems odd for Kim Hak to doubt his own popularity. After coming to photography at the advanced age of 27 in 2008, he has quickly become one of the most successful of the new generation of Khmer visual artists. Winner of two international prizes last year (Photo Quai, Paris and Stream Photo Asia, Bangkok), he has been featured in publications from Rome to Hong Kong; in September he will represent Cambodia in the UK’s first World Event Young Artists festival.

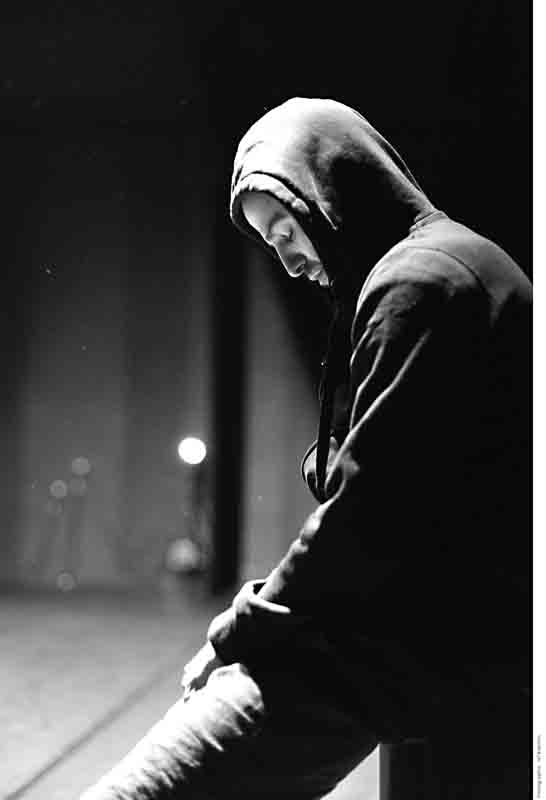

But self-aggrandisement does not come easily to Kim. Serious and soft-spoken, he is self-effacing almost to a fault. When questioned on the complexities of the time-space dialectic in his work, he laughs and claims: “I’m not a complicated person!” When admired for his Caravaggian mastery of chiaroscuro, he looks uncomfortable and scratches absent-mindedly at his tattoo, which reads ‘dawn light’ in Khmer.

Despite such protestations of simplicity, Kim’s photographs are a visual banquet, palimpsests interwoven with ghosts of the past, present and future. He admits to being in thrall to history, particularly as imaged through Phnom Penh’s swiftly changing cityscape: “In (my) photographs, the past and the present are documented for the future, for the benefit of the next generation to study about the city. When I photograph it is part of memory.”

This examination of mutability through the metaphor of architecture characterises much of Kim’s work, and contextualises his inclusion in Meta House’s upcoming exhibition, The New Cambodia. Part of the Free Your Minds festival 2012, sponsored by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation, the show documents the amber moment of today’s Phnom Penh, suspended between the traditional and the assertively modern. Local and international photographers such as Ma ‘Rooster’ Channara and Jeff Perigois will portray the city’s recent development, supplemented by presentations on Cambodia in flux.

Kim’s contribution to The New Cambodia encapsulates Phnom Penh’s limbic state: in the background of the photograph rise Central Market, Canadia Tower and Vattanac Tower, standing for the past, present and future of the city’s self-representation; in the foreground a lone figure, face obscured by a poised camera, attempts to freeze time’s passage.

It is testament to the complexity of Kim’s work that, despite this fascination with the temporal, what initially strikes the viewer in his photographs is the use of space and light. Photographs from past collections combine painterly composition with an acute understanding of human vulnerability. Recent series ON focuses on pensive figures caught in Phnom Penh’s most beautifully careworn buildings, the carefully composed pictorialism of the locations working dialectically with the unpredictability of the human subject.

Kim acknowledges the co-existence of the pictorial and the photographic in his work, attributing it to his creative process: “Normally I go to see the location and check the light and think about the space and the image, what the person maybe adds or how they can move in the space. The photos are between reality and fiction, past and present.”

Figuring time’s passage in this abstract, painterly way is Kim’s leitmotif. Lately he has been drawn to capturing at close range the damp walls of Kep’s ‘ghost houses.’ “Through history all these walls have been affected by nature, by trees and plants, as well as people in graffiti and gun shots, so all the history is there on the wall. Now they’re being destroyed and soon they’ll be gone forever, and they took 40 years to get here.” The photographs, which will be shown in France in 2013, convert this moment of decay into images of impressionistic beauty. Engrossed in his photographs, Kim muses: “I tried to photograph history on the wall… but this one also looks like rain far away. I try to put the fusion of art, and conceptual, and documentary in my photos. I like my photos!”

Red-faced, he remembers he is being interviewed. “It was nice talking to you. I hope you didn’t get bored.” He doesn’t need to worry: with photographs of this complexity and depth, boredom is not an option.

WHO: Kim Hak

WHAT: The New Cambodia photography exhibition

WHEN: July 24

WHERE: Meta House, #37 Sothearos Blvd

WHY: He’s poised for global greatness