While many visitors pass through Mondulkiri, comparatively few make the effort to venture to the neighbouring province of Ratanakiri. Cedric Delannoy’s latest exhibition aims to challenge archaic preconceptions of Ratanakiri, its people and their lifestyles.

…..

Cedric Delannoy’s exhibition Ratanakiri brings a unique insight into the lives of the people of the province to the hustle of Phnom Penh.

“Many people don’t know about Ratanakiri. That’s the case of almost everybody I’ve met; they went to Mondolkiri but they did not make the step forward to go to Ratanakiri. So I thought to myself, “Let’s bring Ratanakiri to Phnom Penh so they can have another view of the province,” Delannoy says.

Delannoy’s collection of black and white photographs was captured over three years, while he worked in Ratanakiri as a technical manager on a food security and nutrition project.

“I was using my camera, reports and Facebook account to document the project, so I was always [working on] it,” Delannoy says.

Delannoy found that at the end of each month he had two or three standout photographs. The result of Delannoy’s three years of photographic documentation offers a rare peek into the lives of people living in Ratanakiri and helps to break the often preconceived ideas by many who have not yet visited the province.

“I want to show that Ratanakiri has changed and is not full of nature anymore,” he says. “Many also think the people wear traditional clothes and so on. Even among the ethnic indigenous people that’s not really the case – only a few of them [wear this] now. All the young people want to wear modern clothes and even in the villages almost all of them wear The Voice Cambodia shirts.”

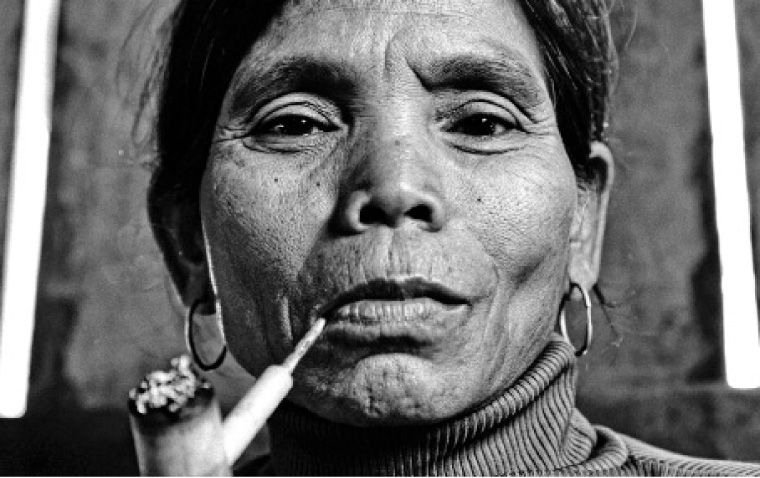

Woman with Pipe portrays an older Tempouan woman looking straight into the camera, puffing on a homemade pipe. The photo was taken during the final technical evaluation of Delannoy’s project. Due to the time needed to translate from the minority language to Khmer and then to English, there were often times when Delannoy could take very few photographs.

For Woman with Pipe, he simply placed his camera in front of the woman at an upwards angle. He wasn’t actually sure what he was capturing, but the result is a powerful image that has become the face of the exhibition. The handmade pipe the woman smokes is decorated with ornate pink detail, invisible in the black and white photograph.

“I did not know what I was shooting,” Delannoy says. “I just took the photo and she was looking at the camera and she was thinking, ‘What’s this?’”

Back to the Village shows an ethnic Jarai family returning home after picking fruit and vegetables. They carry the produce on their backs in backpacks called “kapas”. Traditionally the kapa is made from bamboo, but with the forest’s decline people have started to use plastic, while continuing the traditional method of construction. Delannoy hopes his exhibition can shed light on Ratanakiri and raise awareness of the help that is needed.

“There are still indigenous people, and the conditions there are very hard. In some of the photos we see sadness on the face. I think we should try to do more to help them – help people to get opportunities and to protect the landscape,” he says.

None of the subjects in Delannoy’s photographs were asked to pose or go to a certain location, and the editing process only involved minor corrections such as adjusting the contrast or cropping.

“All the pictures in the exhibition we can liken to photojournalistic reportage, because it’s really natural.”

Ratanakiri shows at Bophana Centre,

#64 St. 200 until June 16.