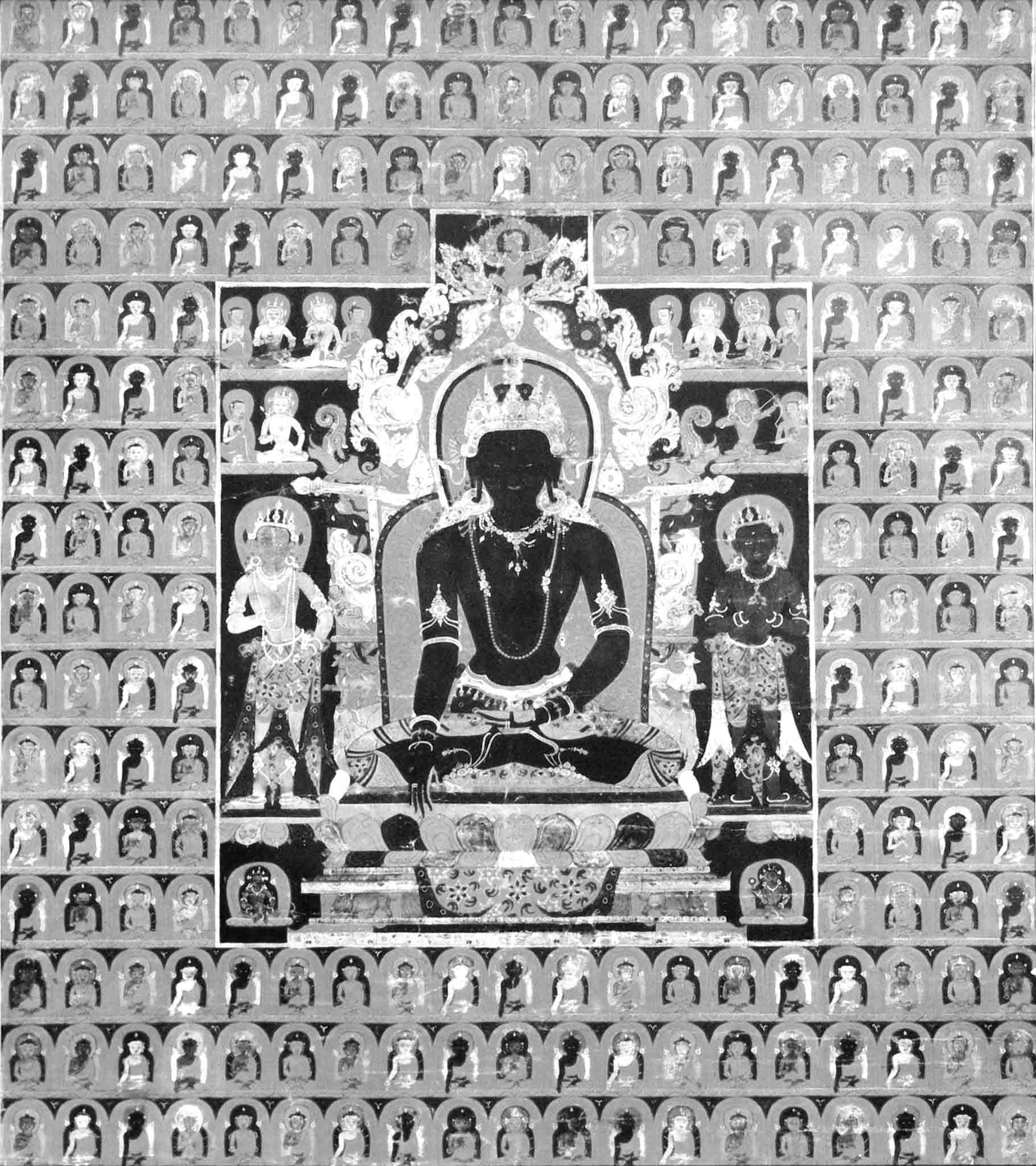

Since 1958, tens of thousands of speed freaks, pill poppers, crack addicts, junkies, glue-sniffers and alcoholics have arrived at Thailand’s Wat Thamkrabok to undergo the world’s most extreme drugs detox regime. Set against an idyllic Oriental landscape, this stark Buddhist monastery is a far cry from the usual celebrity-friendly rehab haunts. Every day, patients line up to swallow a bitter herbal brew made from 108 local seeds, leaves and tree barks which leaves them retching and spewing in the gutters as their ‘drug demons’ are exorcised (to this day, only two monks know the recipe – a closely guarded family secret). Known as ‘Junkie Monastery’, it’s considered the world’s toughest rehab: here there are no toilets, air con, telecoms, hot water or private rooms. Wat Thamkrabok, which translates as ‘Cave of the teaching,’ is a lofty temple complex 130km north of Bangkok which was founded in 1957 by Thai nun Luang Paw Yaai. There, perched atop a mountain and in response to then-Prime Minister Sarit Tanat’s campaign against drug addiction, Luang Paw Yaai developed what is today the world’s most notorious detox programme. In 2004, her brutal vomit cure proved too much for self-destructive Libertines’ front man Pete Doherty and the heroin-addicted British musician bolted on day three of what should have been a ten-day purge. Here, one of only a handful of Western women ever to pass through the world’s toughest rehab describes – on condition of anonymity – her own experience as a heroin addict within the walls of Junkie Monastery.

How did you first hear about Wat Thamkrabok?

I’d seen it on the TV show, Taboo: ‘insane remedies’, this was one of the places featured. It looked bad, but it didn’t look horrific. The whole thing was about throwing up to rid yourself of toxins and the whole ritual thing to cleanse your energy. It sounded bizarre to me. The story was about two heroin addicts from England, but all you got to see were the rituals – and you know the standards aren’t like a Western rehab.

There were 45 Thai men, mostly brought in wearing shackles on the police paddy wagon. A lot of them were busted for selling or distributing drugs in Bangkok, a lot of gangsters. Some were as young as 14, but they were already in gangs. Then there were 13 Western men… and me.

You can’t run away. It’s about an hour-and-a-half from Bangkok, but once you’re there it’s like a huge village. There are these big gates with two huge elephants holding the globe, that’s Thamkrabok’s symbol. When you go in it’s like a community: there are houses, roads and cars. Once you’ve done your first five days of vomiting, you’re allowed outside to do chores. We had to wear red nurse’s scrubs – at least, that’s what they looked like – and apparently on the back, in Thai, it says: ‘Winner.’ [Laughs]

Charlie Sheen would appreciate that.

You didn’t feel as if you were a winner; not at least until day ten! Inside the temple, the area for inmates is called The Hey and you’re locked in. As a girl, I was locked in from the outside – padlock on my door and bars at the windows – at 8pm and unlocked at 5am. The Western guys weren’t locked in at all, nor were the Thais.

For your own safety, presumably?

Yeah, but why not lock the guys in and let me out?! What am I going to do? For one, to go through any experience like that alone, knowing you’re not actually alone, is one of the most horrible feelings. Even though you had the safety of knowing everyone there was going through similar things to you, as a female you’re locked away and so you don’t get the time to talk to anyone unless it’s during daylight. For the first five days, because you’re coming off things, you’re so sick you’re not trying to talk to people. At night, you can’t sleep: I didn’t sleep at all, not one minute, in nine days – and that was very common. People would go 14 days without sleep and get delirious. I could feel that I was losing my shit, but I just couldn’t sleep.

At five in the morning the bell rings, this huge fire alarm, and then you get out and grab a broom and start sweeping the compound. The Westerners were all in one building, guys and girls. There were ten steel or wooden cots with little shelves – no drawers – where you could keep snacks and soap. They provide you with a basic sheet, but they advise you to bring your own bed linen. When you’re detoxing, you get really restless and sweaty and you have a fever and it’s hot and there are fans, but you’re freezing. You have all these mixed feelings and you can’t get your body to regulate. There were three other Thai women in there while I was there. One was probably only in her fifties but looked like she was in her seventies: she’d been drinking since she was 11 or 12 years old, daily. She would have seizures: she’d be sitting up, brushing her hair, then she’d look at the light and all of a sudden her neck would spin around like The Exorcist and she’d fall on the ground and have this massive seizure. I knew what to do, luckily, but the other two women were terrified; they thought she was possessed. Imagine you’re locked in and this woman’s having a seizure and these other two women are screaming and you have to wait for somebody to come with the key and unlock you. They’d run in and start sticking things down her throat, trying to stop her from swallowing her tongue. They didn’t know what to do, but this happens a lot – especially with methadone and alcohol. You’re advised to stay clean for two days before you arrive at the temple because those are the most common times for seizures to occur and you can get properly treated for it, because once you’re at the temple, if you’re having a seizure, you’re having it at the temple. Bangkok is an hour-and-a-half away, if you’re lucky, and the monks aren’t going to take you. They actually tell you: ‘We’re not taking you to a hospital. This IS the hospital.’ Then they pointed to this cell – the hospital was the same as the jail. If you went mad while you were in there, they would shackle you up in that room and lock you in from the outside. It was a dark room in a corner with one ceiling fan and a mat, littered with mosquitoes.

You were allowed to bring in reading material, like books, but nothing electronic. I brought 15 pairs of underwear because I wasn’t planning on doing laundry while I was there. When you get there and check in, they give you three bags of soap and your starter uniform. The nun who let me in said: ‘Have you never washed your clothes before? Do you really need this much underwear? Pick your favourite five.’ [Laughs] I think part of it is that they don’t want it to become a trading situation. You can’t bring in your own clothes and you’re not allowed to change out of the uniform at any point. It’s red, it’s oversized: there’s no sex appeal. You’re in a temple at the end of the day and coming off certain drugs, like opiates, the female sex drive is supposed to increase. They don’t want that to play a role in anything that happens at the temple: someone goes to detox and comes back pregnant? Not a good review. That’s the gist of the welcome you get and what you walk into.

What brought you to the point where checking into ‘the world’s toughest rehab’ was something you felt you needed to do?

Watching Taboo and seeing these two junkies, who’d been doing it to themselves their entire life, have to wait for a TV show to straighten them out. I’d been doing drugs for a long, long time. I’m 29 now and would say I’d been doing them daily since I was 13, in some form or other. I’d constantly been on something. I knew it had gotten out of control several times, but I’d just move countries – usually to somewhere with harsher drug laws, because I wanted something to stop that temptation. I’d try not to be in places like Cambodia again, because that’s where it got really bad. I thought: enough’s enough. Just go and do it and if this isn’t going to work – it’s the world’s toughest rehab, plus I mentally want it to work – then nothing is going to work. You don’t go through something like this because you ‘want the experience’. I realised that if I kept going like I was, in six months I’d be dead. Sometimes it takes more than willpower; it takes being in a really disgusting place and having a really bad experience that you can associate with all the things that previously made you feel good about bad things. It’s like you eat something and, even if it’s your favourite food, if you find half a cockroach in it you’re probably never going to eat it again. Negative associations, that’s what I wanted. Here was something that was going to make me feel horrible and I hoped to god I would remember how I felt when I came out of it.

So that was it: I wrote to the monastery and gave them my background. Normally they say seven days is the minimum, but 14 days is the suggested stay. To stay longer than 28 days, you need written permission from the monastery. They said to me: ‘We recommend you stay three months.’ There are blogs by people who’ve been there, but I’d never read anything about anyone being asked by the monks to stay three months. They asked because of the length of time I’d been using drugs and how functional of a person I was when I was on them; I think they understood it was more than just a ‘weekend warrior’ problem. I’m really good at using drugs and living my life ‘normally’, because that’s the only way I had ever lived my adult life. Being sober isn’t an option, because I don’t know how to live that way. They realised what my position was – and, at that time, I was the principal of a school. You become so good at being a regular person, with no visible financial or personal problems; everything seems to be under control, so when does it become a problem? When you wake up and you can’t get to brushing your teeth because all of these other things come first. That’s when I decided I needed to go. I was 28.

How long did you stay at the temple?

Fourteen days, during a national holiday. Two weeks was the longest possible time I could take off school. Three months probably would have been better for my rehabilitation and if I was sitting on a yacht with piles of cash I’d probably have stayed on at the monastery for six months. At day three, I’d taken a walk around the wat and worked out escape plans. The only thing is they keep your passport and your real money. To operate on the inside, once you get registered they take your passport and all of your belongings and they lock them up. The head abbot is the only one who has keys and you’re not going to rob this 90-year-old man. It’s very clever. Nobody’s going to rob this sweet little old man because he’s all the way up a fucking mountain and you’re not climbing up there. They count your money and log it then they give you the same amount in Monopoly money: temple money. They recommend you take 200 baht a day, which is more than enough. On my last night I bought everybody dinner, because I had all this leftover money, and it was less than 400 baht.

Did you make friends while you were there? Was that even possible?

Yes, it was. Being the only female, I think it was good for the guys, too. Being around so much testosterone when people are going through withdrawal – and they don’t see any other women, when probably the people who managed to get them into this clinic were women: aunts, sisters, mothers – and then they’re thrown into this pit, essentially a prison, where you’re sharing a toilet with god knows how many men. Up to 30 can fit in a room; luckily there were only 14 or so foreign men while I was there.

Did it help, having other foreigners with you while you were there?

Because I was the only girl, they would look after me. In the steam baths, you’re all wearing your robes and you exit the prison area and walk out onto a road down to where they have ceramic-tiled steam baths. At the back, they stick wood and a whole bunch of herbs – stuff like cloves, which smelt like it would make a good barbecue – and spices. All of the tea is made from this potion thing that you drink, so everything reminds you of this horror and you have to drink it. Some of the guys told me to surreptitiously pour it away. You have to drink it at least three times a day, but they give it to you six times a day and it’s there, out, the whole day, so you can drink as much as you want. In theory, if you want to get better as fast as possible, you do what they tell you to do when they tell you to do it, but there are so many other things going on in your head than drinking that fucking tea! Drinking tea to get better isn’t something that seems logical at this stage. You’re already going through Hell and you’re, like, ‘What’s another hour?’ Everything merges: you haven’t slept, you haven’t eaten. All you do is you have diarrhoea, you’re shitting yourself, you’re puking all over the place; it’s just a horrible, horrible experience.

How horrible can herbal tea be, really?

When you walk into The Hey, the first thing you see is this door and then behind that is a trough. Behind that is a tree where people stand watching you and banging drums. You have to kneel – you want to get as low as possible. When I got there the first time, one of the monks came over and gave me an elastic band. I thought it was for my hair. ‘No, it’s for your shirt,’ because you’re wearing this oversized jump suit and you’re leaning down. I was wearing a bra but you’re not allowed to wear tank tops or anything else like that, so I guess it was just boobs and these poor 90-year-old monks are going to walk past, banging their drums, and they’re going to see these boobs out. [Laughs] So the monk gives this elastic band to me to tie up my shirt and I’m holding my hair back, thinking: ‘Don’t you have another elastic band?!’

The first day I walked in coming down off heavy drugs. The last time I had taken heavy drugs was two hours before getting on that plane. ‘I know it’s not OK to get to Bangkok high, but at least I’m not doing it in Bangkok,’ so I did my last little hit. When I checked into the temple, I still wasn’t feeling great. The nun gave me a schedule: ‘You’re up from 5am to 8pm and there are a few mandatory things you have to do; puking is at this time; sweeping happens five times a day; in between puking and sweeping, there’s a steam bath…’ Three times a week there’s chanting and you have to go up to the temple with the monks who chant for an hour and you have to kneel again. And this is a broken knee, so I don’t kneel very well; it’s really painful. As if that wasn’t bad enough, there’s meditation, only you can’t meditate because everything hurts and your head’s a mess. You can’t be one with fucking anything! You’re trying not to shit yourself; you’re trying not to vomit; you’re trying not to wipe the sweat that’s running down your face; you’re trying not to scratch the mosquito bite on your face or slap the mosquito that’s buzzing around your ear. This is you ‘meditating’. As a drug addict, coming off all of those things, just being alive for the first day is really, really rough. Being alive and then being told you have to do things, when basically you’ve lived your life in a world where you do all the things you know you’re not supposed to do already… and now you’re being told you don’t have that option.

In the morning, at 5am, you come out and you drink this tea that’s supposed to be good for your kidneys. You have to sweep – and if you can’t walk, you have to use the broom as a walking stick and you lean on it, but you have to go outside and you have to take part in the sweeping. That’s pretty difficult to do at 5am for someone who’s sober and alert and not hungover. Can’t you do anything else? Can’t there be a bell and we can go paint?! Or a bell and we can go dance or write or read or listen to music, anything other than sweep and puke?!

Having seen the documentary, the reality of Wat Thamkrabok still came as a shock?

They don’t show you all this in the documentary. In the documentary, these people get up; they puke; they sit around; they feel like shit; they talk to some people; they go to sleep; they wake up five days later feeling fine; they leave and they’re cured. But when you get there, that’s not what it’s like at all. I didn’t feel as though anything in that documentary was real, apart from the vomiting. Let me tell you about the vomiting.

Please, do tell us about the vomiting… [Grimaces]

The first day I walk in, the nun says: ‘Go into your room and get settled. In half an hour, you have to vomit.’ Can I wait until tomorrow? I just got here! ‘No, that’s why we tell you to arrive before this time because that’s the intake and then you vomit right away. Because if you’ve taken something today – and I bet you have…’ [Laughs]

She had you sussed already?

Yeah! She was kind of like you in that sense. She was a very smart lady and she knew what she was talking about because she’d experienced it all herself. She wasn’t a ‘holy woman’, she was an ex-heroin addict who’d had a boyfriend in a motorcycle gang; spent years on the Rainbow Warrior with Greenpeace; drove her kids through Spain for months at a time and, all this time, was a heroin addict – for 18 years – and no one knew. She originally went to spend two weeks at the monastery but, by the time I met her, she was in her eighth or ninth year there, shaved head and everything. ‘You think we’re just going to let you be high your whole first day? Like the other inmates aren’t going to want to kill you? It’s best if you just do this…’ All the other guys were saying: ‘Ooooh, it’s the new girl! Are you ready to puke?’ And they tried to be funny, but don’t be funny; now’s not good. Be funny in 10 days. So she takes me to this trough, where the monk has a two-litre bottle filled with this sludgy brown liquid. You hear that and think Jagermeister, but it’s not: it’s like vomiting granular bits of herbal tea. There are 108 herbs in this remedy, picked by the first ever nun – the woman who started it all. She’s gone off into the hills and had this vision of all these things she needed to pick to cure the world.

Eye of toad, tongue of newt…

[Laughs] Pretty much! ‘I’m going to take 108 of the most disgusting things in the world, put them in a bottle and we’ll make them drink THIS!’ This recipe has only been passed down through her family: she had two nephews and taught them how to make it. One of them was the monk looking after me. They bring this potion to you; they walk in and they’re already playing the drums. He does this thing to get all the sludge off the sides and then they give you a shot glass and two litres of tea. All the people who’ve finished the puking, who’ve been there more than five days, are standing opposite, cheering you on. On the first day, the nun said: ‘Pretend it’s a shot of alcohol. Swallow it completely, get it down. Just open your mouth and get as much of it into you as possible as fast as you can because that will make you puke.’ So you drink this tea and you hope it comes back up, otherwise you have to keep guzzling it down until it makes you retch. She said: ‘Don’t stick your two fingers down your throat; you’re not bulimic and trying to puke in the privacy of your bathroom. Take your four fingers and stick them in there; get your fist in the back of your throat. If you don’t make yourself vomit, you’re going to be ill and you’re going to taste it all day.’ I took one shot glass and it tasted horrible, but it’s not the worst thing ever at that point. My eyes were tearing because I was coming down off all these drugs, because I was vomiting and because I was horrified: all these guys weren’t looking at the other guys, there were all looking at the new girl, me. By day two, you know just how horrible it was and what it would be like having to puke it up. It becomes a lot more difficult every time. On day two I went to the front, but they said: ‘No, you’re not new any more.’ Huh? What do you mean? I just got here! ‘No, at this point there are already other new people and they get to go at the top of the trough.’ I had to go to the end of the trough – and there’s a difference being at the end. There’s this guy who walks around with a garden hose to wash stuff down the dry, concrete trough, because when you’re at the end you’re behind 25 other people and all of their vomit. There are some big, massive Thai guys, who right before vomiting would eat as much as they could possibly eat: two, three, four bowls of rice and stuff, so that when they had this liquid all they had to do was stick one dainty finger down their throat and all of this stuff would come up. They just need to puke once or twice and then they’re good to go. It’s much harder on an empty stomach, when you’re relying on just the tea. At the end of the trough, where you can smell and see and hear everyone else, it’s absolutely horrific. Then they start to pull newbie tricks, like they’re the veterans: ‘New girl, you’ve not eaten for four days. Eat water melon!’ It is really good for you – it has sugar in it and it will rehydrate you. What they don’t tell you is that when you eat water melon and then puke, it comes up all stringy, like Silly String. Sometimes it gets stuck in your throat and you have to pull it out. And they’re all watching – because they’ve all told each other you’ve just eaten water melon – like something funny’s going to happen. Is the monk going to not make us puke today? ‘No, the monk’s coming.’ Then you puke and they’re all yelling: ‘Ohhhh, there’s the water melon!’ You arseholes! It doesn’t matter that you’re in a place of worship; you put a bunch of boys together with one girl and they’re going to be boys.

And this is them looking after you?!

They did, like in the steam bath. Each has 30 people and it’s not very big: maybe six feet long and three-and-a-half feet wide, so you’re sitting on each other. Everybody makes themselves the smallest they can be. The guys get to take off their clothes and wear sarongs, but you’re a girl so you have to keep your scrubs on. You’re pouring water on you and it outlines your boobs and some of them men in there haven’t seen a woman in months, but I would go in and some of the big guys would sit around me, so I always felt protected. They were good about that kind of stuff. Even the Thai guys were respectful: I think, above everything, they knew they were in a temple and that’s something they’d grown up with. No matter how bad a guy he was on the outside, they respected that they were in a temple surrounded by holy men and they needed to behave, although you never know what could happen and I suppose something might have happened a long time ago that led to the women being kept in cages.

Some of these women stay on as nuns.

The nun who looked after me swore all the time: ‘If you think you’re going to get out, you’re not going to fucking escape.’ Are you allowed to speak like that? Isn’t there some rule against nuns using the F word in every other sentence?

This is the second week we’ve had a swearing nun in our cover story.

[Laughs] I saw that! She said: ‘Well, I wasn’t fucking born a nun!’ She told me all about her life. Her daughter is going to come see her this summer for the first time in nine years; she was 14 last time her mother saw her.

Did she regret her decision to stay on?

I asked her that and you could see in her eyes that she was sad on a lot of levels, but she was happy on a lot of levels as well. She wasn’t tormented by her decision; she knew that she’d made the right one for herself and her kids. She wanted to be there for her kids, to be sober and healthy for them, but she doesn’t trust herself yet to go back and not fuck it up. Maybe she’ll never be comfortable with that. She said: ‘Maybe, but I’m not ready now.’ Jesus! The monks do this long walk thing, this meditation retreat, and at first she’d thought it was this Woodstock-type party. This one guy said to her: ‘No, it’s not like that. The music is chanting and you can’t dance to it and we’re out here for days. It’s going to be a lot of silence and a lot of praying and that’s it.’ She felt pretty stupid because she’d come in as this wild child thing. She later watched this same guy leave and stay sober – he comes back now, ten years later, to lead meditations – but she knew that couldn’t be her. She knew she couldn’t leave and come back ten years later and still be sober. On my last day, I said: ‘It’s weird. I hate this place, but I don’t know that I’m ready to leave.’ She said: ‘Stay! You could be like me.’ I don’t think I could stay for nine years, but she’s still not at that stage where she’s ready to leave.

What stage are you at?

I’m at the stage where I go back and forth. I managed to do this and come out of it and I was OK for a while, staying away from anything that might tempt me, but then I got to the stage where I had been sober for more than a month and I still wasn’t feeling like myself. They say it takes 21 days to change habits, but by 22, 23, 30, 32, I still felt the exact same. I was waiting for enlightenment to come, but it didn’t. The monks had said that, realistically, it takes three months for your brain to build up serotonin and dopamine and start releasing it normally. I’d got to the stage where now I was this sober person, but I wasn’t able to do the things I was good at before: I didn’t want to be around people; I didn’t want to socialise. I wanted to work, go home, turn on the TV and tune the world out. I’d expected life to become easier and I suppose it would have if I’d stuck it out for a lot longer. I felt as though I didn’t know this sober person, because the last time I’d been sober I was a teenager. I didn’t realise how much of an impact drugs had had on my life; I didn’t know who to be without them. I read somewhere that alcohol is the worst drug for others because it brings out the arsehole in you, but sobriety is the worst drug for you because it brings out the arsehole in your friends. Sober, I realised I didn’t really like these people and the world was a pretty depressing place.

I made a conscious decision to go out and do drugs again. I remember getting them and being really disappointed and then doing the drugs and feeling really disgusted with myself and then I got really sick and threw up all over the place. Straight away, I could smell the temple and that stuff again and it made me feel really bad, which was good. When that first sickness came, all of these associations came with it and then I didn’t do it again for another month. After slipping up that first time, I felt so much better because I knew the drugs were within reach and I’d done them and I didn’t want them any more. That’s kind of where I am now. Never before have I been able to consciously look at it and say: ‘I’m done.’ I make sure I’m not doing it all the time and that it doesn’t become a problem again. Some people are able to stay at the temple for two weeks and be fine. Some people fight with it for the rest of their lives and that’s probably where I’ll be, but it doesn’t feel like a fight right now. It’s me being conscious and knowing what decisions are right for me: knowing what I need, when I need it and when I need to stop.

Having survived two weeks in the world’s toughest rehab – the one Pete Doherty famously quit after just a few days – was it worth it?

Yeah, it was definitely worth it. You can only go once in your life; they won’t allow you back. You take your vow when you arrive, your sajja, promising that you’re not going to use these things again. At the end of your time at the temple you eat this vow, which is on rice paper, and it’s supposed to stay with you; by passing through your body it’s accepted by all of you. Pete Doherty was there for three days then he escaped: he jumped over the fence and had his manager waiting up the road, with a car full of smack. He’d asked online for his fans to donate money so that he could get out and he got an emergency passport somehow. Believe me, I looked for ways out! Even now, in some of his latest interviews, Doherty has said he wants to try again, but you can’t go back to The Hey, no matter what: the monks won’t let you. Sometimes I wish I could have stayed longer because I would have understood more about how my brain works. Because you can’t go back – and you’re not going to make yourself vomit – what you do is try to put your mind back there and remember what it was like, all those negative associations that got you through. A lot of people overdose in Bangkok within hours of leaving the temple because their bodies have been through such a hard detox and when foreigners die, their bodies are brought straight back to the temple and placed at the top of the mountain, where it’s supposed to be super haunted. I knew that was a very real possibility.