Asia’s largest mixed martial arts event is kicking open the doors for a new generation of Khmer fighters, but are they ready?

…..

US senator John McCain has likened the sport of mixed martial arts to human cock-fighting. And there is no denying its brutality. The point is, after all, to beat your opponent unconscious. Cuts, bruises, broken bones and concussions are common.

Like sex, violence sells – and sells big. In the span of a few short years, MMA has rocketed from relative obscurity into a full-blown worldwide sensation. The sport’s two largest promoters now dominate a global market worth billions.

Ultimate Fighting Champion, the industry leader, began in 1993 as a single event in the United States. UFC now beams regular pay-per-view shows to more than 130 countries in 22 languages. The company is reportedly worth upward of $2 billion, making it the most valuable sports franchise on the planet, surpassing the New York Yankees baseball team and Manchester United football club.

UFC’s Asian rival, the Singapore-based ONE FC, controls 90% of MMA markets across Asia. Through deals with ESPN, Fox and Star Sports, the ONE FC promotion broadcasts to more than 70 countries and counts more than a billion viewers. The sport hit Cambodian airwaves in early 2013, broadcasting on CTN affiliate MyTV.

Now, after 18 months of watching the brutal television spectacle, Cambodian fans will get a chance to see the real thing come September 12, when ONE FC arrives at Koh Pich Theatre with its multi-million dollar leviathan. Titled ONE FC: Rise of the Kingdom, the card comprises five international and five local bouts, including a four-man grand prix.

For Cambodian fighters and fight fans, the night offers a chance to finally bask in MMA’s big-money pomp and pageantry: at the global top end, the sport offers lucrative promotional deals, valuable sponsorships and jaw-dropping pay cheques. But down in the local trenches, where air-conditioned gyms are unheard of, the training is brutal, the paydays are meagre, and the modern world of fight science may as well be written in Martian.

Most importantly, the local matches guarantee a Khmer will win on a ONE FC card, something that has eluded the Kingdom’s fighters in five attempts so far. For the eight Cambodian fighters on the card, all of whom are making their ONE FC debut, it also means the biggest payday of their respective careers. Fighters are guaranteed $1,000, plus a thousand more if they win.

By contrast, big-name fighters in Kun Khmer, the Kingdom’s traditional kickboxing style, typically earn between $80 and $100 for local bouts and occasionally as much $200 or $300 for international matches. Local MMA fights pay better, around $150 regardless of outcome.

Yet as hefty as a $2,000 winning purse may appear, it pales next to the One Warrior Bonus, a whopping $50,000 cash prize awarded to any combatant who can suitably impresses ONE FC boss Victor Cui with his or her “warrior spirit”.

Oh, yes. Her. Girls fight, too.

“I can’t wait,” says Tharoth Sam, a 24-year-old female fighter known as Thalon Thon (‘Little Frog’), about her ONE FC debut. Sam trains at the Afighter Team gym, one of only three MMA clubs in the country. A native of Banteay Meanchey, Sam found her way to the cage after years of training in Bokator, the Kingdom’s traditional martial art, and fighting Kun Khmer.

“In Bokator, some girls think it’s too dangerous,” she says about fighting in the ring or cage. “But I wanted to use what I had from Bokator in a real fight, to see what I can do, to see how confident I am.”

The art of killing

The roots of Bokator stretch back to the time of King Jayavarman VII and the Angkorean Empire. History suggests that ancient Khmer dominance of Southeast Asia was due in large part to the Kingdom’s superior battlefield skills. The Angkorean army used Bokator in hand-to-hand combat, and the ancient discipline incorporated striking, weapons and ground-fighting techniques.

Bokator is widely believed to be the predecessor of modern Kun Khmer. Bas reliefs at the Angkor and Bayon temples depict warriors striking with elbows and submitting opponents with choke holds and arm locks. Proponents point to such carvings as evidence of the Khmer’s innate warrior heritage and, like Angkor itself, the art taps deep into the national identity.

Like many traditional martial arts, however, the true history of Bokator is shrouded in mystery and lore. If ever there was a written record, it disappeared during the Pol Pot regime.

A new Bokator began re-flourishing in the mid-2000s under the direction of Grandmaster San Kim Sean, the art’s most vocal evangelist. The grandmaster spent months canvassing the country in search of old teachers and new students.

Cambodia held its first modern Bokator championship at Olympic Stadium in September 2006. Practitioners mostly competed in forms and weapons demonstrations. Deadly battlefield techniques do not easily transition to competitive sport, the grandmaster says. What little actual fighting occurred took place on wrestling mats. Competition was confined to a large circle. Fighters wore traditional loin cloths, with only kramas wrapped around their heads and hands, no gloves. A drummer beat out hypnotic rhythms tracing the ebb and flow of the action.

Only men fought, and at the lower levels the fighting looked a lot like a schoolyard donnybrook. Competitors were often badly off balance and swinging wildly from the hips. Whatever claims Bokator makes to being a complete art, fighters were not allowed to compete on the ground for more than a few seconds. Even at the highest levels, the champions looked merely like novice Kun Khmer fighters.

That was admittedly the first year. But Bokator still has yet to establish itself as a viable combat style, much to the frustration of its supporters. “The ground fighting in Bokator is extremely weak compared to Brazilian jiujitsu and wrestling,” says MMA fighter Antonio Graceffo, who holds a Bokator black krama (equivalent to a black belt in other disciplines). Jiu jitsu and wrestling have heavily influenced the ground-fighting styles of modern MMA. Bokator supporters believe that, with proper training and support, their art could hold its own against those disciplines. And among the faithful, there still smoulders the dream that someday soon Khmer fighters and the Bokator style will take their rightful place among modern mixed martial arts.

Little Frog, for one, is not giving up. “Some people say that Bokator trainers can only dance and perform, that it’s not for real fighting,” she says. “Those kinds of words motivate me. I’m going to show those people: Bokator is not just for dancing, not only just for performing; we can fight, too.”

A boy from Brooklyn

Chan Reach was born in the US to Cambodian parents on 13 June 1988, and grew up in Brooklyn. Raised by his grandmother and an uncle, Reach doesn’t remember a time when he wasn’t involved in the fight game. He began training with his uncle at an early age, started fighting Kun Khmer around 16 and moved into wrestling then jiu jitsu and MMA after that.

As he grew older, Reach made regular visits to the Kingdom. He moved permanently to Cambodia in December 2012, taking the position of head trainer at the newly formed Afighter Team gym in Phnom Penh. He is one of four fighters in the ONE FC grand prix.

“When I was in the States, I always wondered: Cambodia, we have fighters, we’re freakin’ born fighters. Why don’t I see enough Cambodians in MMA?” he said. “As a matter of fact, I didn’t see any at all. So I decided to just quit my job, leave everything behind and come here to bring MMA to Cambodia.”

Reach was not alone in his ambitions and, when he landed, Dave Minetti at the K1 Fight Factory was busy with similar ideas, too. The former French legionnaire was looking for Khmer fighters to train in MMA striking and grappling. He was drafting rule books, designing logos and collaborating with Vath Chamroeun, secretary general at the National Olympic Committee, to create an official MMA governing body.

There were others, too. Across town at CTN, the station’s well-known head of sports, Ma Serey, had been trying for years to get Bokator on television. He had even run a few untelevised dress rehearsals, but there simply weren’t enough quality fighters to make weekly bouts viable.

Encouraged by his general manager and backed by the station’s powerful owner, Kith Meng, Serey was now pushing to get MMA onto his airwaves. But almost nothing was going his way.

“I contacted Bokator,” said Serey of those early forays. “But Vath Chamroeun said it was impossible. ‘We cannot do it because there is a lack of fighters. We cannot find fighters for every week.’”

He spoke next with the president of the Cambodian Boxing Federation, the influential body that oversees Kun Khmer and professional and amateur boxing. “I went to see Tem Moeun, but he also refused. He was afraid of Bokator, of Vath Chamroeun, because MMA is not under his responsibility; he’s only Kun Khmer.”

With no fighters or sanctioning body, Serey was stuck. The others were facing different but seemingly impossible challenges, too. Over at K1, Minetti, who was now technical director of the newly established Cambodian Mixed Martial Arts Association, was short on quality students. And while Afighter Team had managed to attract a dozen or more brand-name Kun Khmer fighters, converting them to MMA was proving more time consuming than originally planned. But none of that mattered, because for all the men’s efforts, without a sanctioning body, without rules and referees, fighting was exactly what Vath Chamroeunsaid it was: impossible.

Quitting, however, wasn’t really an option. “‘Bong Serey, We must do it,’” implored the station’s General Manager Pol Vibol. “’I like it. Even the oknha [Kith Meng] likes it and supports us and wants this to happen. You must make it happen.’”

In previous years CTN had found success with a reality series called Kun Khmer Champion. The show pulled 16 fighters together to live and train. Through regular bouts, the pack was whittled down to two final contenders, with the winner of the ultimate match crowned the season champion.Serey put out an open call for fighters and quickly gathered two-dozen strapping young men in three weight classes: 57, 60 and 65kg.He modified the show’s format to cater for cage fighting and called it Kun Khmer Warrior Champion. To kick off the inaugural season, CTN scheduled two international cage fights as part of the station’s massive 10-year anniversary celebrations at Koh Pich.

Behind the scenes, however, negotiators at CTN and the newborn CMMAA had failed to reach consensus over referees and sanctioning fees. Tem Moeun and the Boxing Federation, sensing a second chance, quickly stepped in and agreed to sanction the bouts.

So on the night of 8 March 2013, Serey stood in the middle of a six-sided ring – a full cage couldn’t be built in time – and delivered an elaborate explanation of the new sport to thousands of onlookers. Not once did he mention MMA.

Backstage, Chan Reach wrapped the hands of Say Teven. Beside him, Little Frog offered words of encouragement. But both knew – in fact, everyone knew – that the two Cambodian fighters were heading towards near-certain defeat.

Minutes later, Chuth Chunlee tapped under a barrage of punches from the mounted position at 3:42 in the first round. Teven, a durable veteran from Siem Reap, made it to the second stanza, when he tapped to an arm bar with 1:15 left. Quietly people complained, but few dared openly criticise Serey or CTN.

Fight club

The Cambodian MMA Association officially launched four days later with a small press conference on the second floor of the National Olympic Committee building. If the pre-launch CMMAA remained muted in its opposition to ‘unsanctioned’ MMA bouts, the officially stamped CMMAA was loud and unequivocal: nothing regarding MMA could happen without the CMMAA’s express approval.

The position put the newfound sports body and CTN on an inevitable collision course. After the station announced a second international MMA card just weeks later, tensions simmering behind the scenes boiled into public view.

Dave Minetti, now the CMMAA’s technical director, fired off a missive blasting the event and warning those involved. “[The] CTN MMA show is an illegal event,” Minetti said. “[CTN didn’t] get CMMAA approval. They don’t respect MMA rules. Their referees and judges are untrained and not qualified. The CMMAA will not allow any fighters who compete in CTN’s event to fight on any CMMAA official show or The ONEFC.”

Tough rhetoric, but on the ground the words had little effect. For one, boxers are rarely involved in decisions regarding their opponents. They fight who, when and where their trainers tell them. Further, active Kun Khmer fighters had little reason to fear the CMMAA because Kun Khmer falls under the protective wing of the Cambodian Boxing Federation, which had a long and close relationship with CTN. But most importantly, the television station had one important thing that the newly formed MMA body did not: money. For all its big aspirations, the CMMAA was operating with a near non-existent budget. And without purse strings to pull, everyone knew its words would be difficult to enforce. Im Ouk, owner of the Afighter Team, echoed what many at the time were thinking. “The CMMAA doesn’t have any clubs or any professional fighters,” he said. “All they have is their association, which I see has no credentials in this sport.”

Still, the division between the two heavyweights would cast long shadows. Without the support of Vath Chamroeun, a former Olympic wrestler who was tightly aligned with the National Olympic Committee and the Wrestling Federation, CTN would have no wrestling coaches or wrestlers among its development programme. And because of their excellent skill at controlling action on the ground, wrestlers represented perhaps the finest pool of talent from which to develop new MMA fighters. “The hardest part in this sport,” Ouk lamented, “is the politics.”

Ready to rumble

Nearly 1,000 people packed the CTN stadium in Russey Keo in anticipation of Cambodia’s international MMA debut. The first two matches held in the WWE-esque, six-sided ring at Koh Pich were easy to dismiss as test fodder. “That was just a sample,” Serey said. Tonight, the home team would shine. And Serey and CTN would silence the doubters.

To head off criticism of ‘untrained’ referees, the station hired veteran UFC third man Marc Goddard to workshop with local officials and oversee action during the night’s most important bouts.

For opponents, the station brought in three fighters each from South Africa and the UK. Perhaps hedging his bets, Serey matched the foreigners against three up-and-coming MMA fighters and three seasoned Kun Khmer fighters.

Only Tok Sophorn from Afighter Team won. The other five got bludgeoned. In the second fight, Sam Angdun lay motionless for a full 90 seconds after getting KO’d at 2:26 in the first round. The third bout ended in just 63 seconds. To the horror of everyone, the same storyline unfolded again and again all night long.“ My job is to take them into deep water,” said Goddard after rescuing Kun Khmer veteran Pich Arun from a first-round thrashing. “But I don’t want to drown them. He was clearly a fish out of water.”

If the Koh Pich bouts could be written off as a test run, these six fights, under the critical eye of fighters and genuine fans, could not. The assault on national pride was immense, and the blowback came hard and fast like an elbow to the teeth. “That show was kind of sad,” Ouk said. “I knew our Khmer fighters were better than that. All they needed were proper training and better support.”

The Phnom Penh Post described the night as “shambolic”. Minetti labelled it “ridiculous”. Vath Chamroeum took to the local papers and publicly demanded the suspension of CTN’s programme, calling the bouts “unsanctioned”. Hem Thon, administrative director of the National Olympic Committee, said the fights must “be halted”.

Serey was under the gun, and anger seethed at the highest levels of government. “The Ministry of Youth and Sport called me,” he said. “They said: ‘Serey, you must stop doing this because it’s dangerous. We are not happy. Cambodians are not happy. You brought good fighters from overseas to beat Cambodians in our own house.’”

What Serey had envisioned as a crowning achievement turned into a nightmare. But he wasn’t about to give up. Sure, the sport was new to him, he said, and he was still learning its nuances. Sure, he underestimated the strength of the foreign opponents and, just as mistakenly, overestimated the ability of his own fighters. But losing was better than not trying at all. Not trying was giving up. And Serey was not about to do that.

So back he went to the Ministry of Youth and Sport. “I said to the ministry: ‘How long do we wait? If you start right now, I think it will take 10 years for our fighters to be strong. If you say now we cannot do it and we must wait for 10 years more, that means we will wait until 20 years.” The ministry relented. “They let me do it,” Serey said. “They knew I was right.”

Little Frog

Little Frog got her first taste of martial arts when a friend invited her to the Bokator national tournament in 2007. “The first time I saw it I really liked it. I asked my friend: ‘How can I train? Do they allow female students?’” They did, so Little Frog began training. She was a natural. “When I was young, I really loved sports,” she said. “I played football with the guys and stuff like that. I love the challenge.”

She entered the national tournament a year later and brought home one silver and three gold medals, all in forms and demonstration categories. Winning was euphoric. She was hooked.

In the ensuing years Little Frog has become Bokator’s leading female practitioner and now she’s among the art’s most active evangelists. Bokator has taken her to Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and the Czech Republic, and she’s among the sport’s most ardent ambassadors.

In 2012 she represented Bokator at a regional martial-arts conference in Ho Chi Minh City, where organisers asked the girls to join a beauty pageant. “I didn’t trust myself,” she said. “I didn’t think I could do that because I love to dress up like a tomboy. I don’t know how exactly to walk or do girly stuff. I jumped in because I wanted to get the Cambodian name to compete with them, too.”

She got first runner-up, but being a beauty queen was never the goal. Fighting was. So in more recent years she has diversified her styles, adding some wrestling and Vovinam, Vietnam’s traditional martial art, winning medals in both. Two years ago, she began fighting Kun Khmer in earnest.

“Every time they call me and ask ‘Do you want to fight next week?’ I say ‘Yeah, OK. Put me in the ring.’ One day I am going to fight in an international competition. If I want do that, first I have to be the best in Cambodia.” In 10 fights she has won six – three by technical knockout – and lost four.

If her parents were proud, they were also worried; mostly about her safety, but social pressures weighed on them, too, especially her mother. “She was really worried about me, because, you know, I’m a girl. And she wants me to stay home like a normal girl, take care of my parents, be a nice girl and stuff like that.”

Even though she never told them about her desire to fight, the intuition of Little Frog’s parents kicked in early on. “From the beginning, when I started Bokator, they complained about it,” she said. “They said: ‘Don’t fight. If you train for fun it’s OK, but please don’t fight.’”

The more she trained, the better she got. And the better she got, the more she wanted to train. And the more fraught her parents became. “We had some arguments, too. I said: “Come on, Mum; I’m not doing anything bad. I spend a lot of time on this because I want something more. I want to be the best. I want to be on the top.”

After she lost two consecutive fights, her mum begged her to quit. “She was crying, she was complaining, complaining, complaining every day. That put a lot of pressure on me.” Still, Little Frog couldn’t live with herself if she gave up on her dreams. “Sometimes they really get tired of giving advice to me. Sometimes they stay quiet. But they are sad. And I am sad, too, because I made my parents like this. But I don’t know. I still keep fighting.”

Bright lights

For now, at least, the prospects of the big-time stage have everyone lining up for success. ONE FC seems to have navigated the local waters well: they’ve included everyone and offended no one. Fighters from every club will make an appearance on fight night, CTN will handle local broadcasting and CMMAA will sanction its first official bouts.

Longer term, ONE FC could open doors that have long been shut to Khmer fighters. The pinnacle of a local champion’s career would be marked by a few fights against foreigners for a couple hundred bucks. The Cambodian game has never had international connections and, for the best in the country, the prospects of fighting beyond the local stage were typically zero.

ONE FC now offers a gateway to the world. To get through those doors, though, fighters will have to start winning. Considering the current level of the local sport, which is just barely a year old, there is still much distance to travel. “Our goal now is to look after the younger Khmer fighters because they will be the future of MMA in Cambodia,” Ouk said.

That future begins on September 12 and, no doubt, future MMA stars will one day look back on the local debut of ONE FC with nostalgia and pride. And all the obstacles everyone faced to make MMA happen in Cambodia will seem worth it.

WHO: Khmer Warriors

WHAT: MMA cage fighting

WHERE: Koh Pich Theatre

WHEN: 7pm September 12

WHY: There are few sporting spectacles more exciting than a prize fight

Guesthouse food is the dirty little secret of every self-respecting expatriate.

Barely a step up from street food (but without any of the excitement), guesthouse restaurants cater to backpackers, the wandering jobless and other price-sensitive classes. That clientele often earns eateries a double-barreled blast of bad reputation: not just cheap, but worse – full of tourists.

For years Boeung Kak Lake served as the local outpost for value-conscious travellers and like-minded long-termers. But most of the businesses there disappeared along with the water as developers filled the lake with sand and thuggishly chiselled apart the community.

As a hedge, the #11 Happy Guesthouse, a lakeside mainstay, opened two new places closer into town, including their newly remodelled location on Street 258. They have expanded the front patio, added two metres to the bar, built an air-conditioned movie room and, as of August 15, completely rebranded.

The old #11 is now the new Flicks 3. Gone is the name, but the staff, menu and atmosphere are still the same. And on a street that has veered hard toward flashpacker, the new movie house still saunters with the same summertime attitude that once made the lakeside a haven for holidaymakers.

And the food is still a bargain.

The menu runs to 15 pages, with about half that dedicated to drinks. Food sections include breakfast and burgers, pastas and paninis, Indian and Asian. But just like the old lakeside, knowing where to venture – and where not – can make all the difference.

Western food includes such standards as the cheeseburger ($3.50), cordon bleu ($5) and assorted sandwiches, pastas and pizzas. Some dishes are better than others. The chicken sandwich ($4.50), for example, comes plated with skinny fries and served as a triple-decker with pan-fried cuts of chicken breast and lettuce, tomato and cucumber all stacked between three pieces of lightly toasted bread. There’s plenty of food and you’re unlikely to leave hungry. But there’s also a tendency to over-mayonnaise, and despite the fresh ingredients the sandwich comes out a bit oily, as do the fries.

Conversely, the kitchen nails it with the chicken strips ($4): five thick strips of chicken breast heavily crumbed and pan-fried. The batter comes out golden, rough and crunchy with hints of pepper; the chicken unspiced, moist and tender. The dish screams for a sausage-cream gravy compliment (hint, hint). Instead it’s served with mayonnaise, ketchup and sweet chili sauce, which, all things considered, works just fine at this price range.

The sweet spot of the menu is in the back, where the local dishes are found. Workhorses like fried rice ($3) and fried noodles ($3) are all served in generous portions. The gem of the menu is Khmer chicken curry soup ($3.50), a local adaptation of the more well-known Thai massaman. Flicks 3 serves it with carrots, potatoes, green beans, onion and just enough chili to make breathing easy without watering the eyes. If you’re not starving, the dish might feed two.

Crowds are thin at lunchtime, the service typically quick. At night the place tends to fill with travellers and the 32-seat movie room will only increase the numbers.

If the dregs of lakeside moved into Golden Sorya, the sober ones moved onto Street 258, where a mid-town flashpacker strip has long been growing roots. The newly dolled-up Flicks 3 fits right in. Sure, it’s a far cry from the creaky papasan chairs, foul-smelling waters and blood-hungry mosquitoes of Boeung Kak yore. But that’s a good thing, right?

Cue up John Malkovich and pass the buttered popcorn.

Photography is rarely so delicious – or healthy. In a new food and photo series at Artillery Cafe, photographer Michael Wild documents the process of organic cashew farming. It’s an all-you-ever-wanted-to-know-about-cashews-but-were-too-busy-eating-to-ask kind of multi-sensual affair. In addition to the images, the exhibit includes nut samples and a wickedly delicious short menu of cashew-inspired recipes (raw organic cheesecake and key lime pie, to name but two).

Wild’s show is the first of a multi-part installation entitled Meet The Makers, a see-and-taste series designed to introduce eaters to the origins of local organic food. “We believe that when you know where your food comes from it tastes better,” says Brittany Sims, managing director and owner of Artillery Cafe.

The nuts and images come from a facility operated by Mekong Rain, an organic grower in Kampong Thom. Cashews are big business. Growers and middlemen export some 100,000 tons to Vietnam annually, and Vietnamese buyers in tattered clothes and flip-flops are known to carry armfuls of cash in several denominations, ready to snatch up any loose nut.

But cashews are also poisonous and cracking one is no simple job. “It’s rather nasty,” says Mekong Rain CEO Andrew McNaughton. When cracked open, cashews release an allergenic resin that irritates the skin and eyes and is toxic if swallowed. “You can’t do it at home. It has to be done industrially.”

As Wild’s photos illustrate, workers wearing industrial-strength latex gloves open cashews using a hand-operated cracking machine. The nut inside, while technically edible at this point, remains covered with a mildly caustic reddish-brown skin that burns the lips and leaves a slightly bitter aftertaste. While cashews are almost never sold or eaten this way, McNaughton and a few other die-hard fans argue that, stinging sensations aside, cashews are at their most delicious at this stage of the process.

Anyone who has tasted the organic ‘cheesecake’ at Artillery, however, is unlikely to arrive at the same conclusion. Made from a narrow handful of ingredients – almonds, dates, cashews and, depending on the cake, some flavourings – the cheesecake is every bit as rich and creamy as anything made from real dairy. “Cashew nuts are naturally high in healthy fats,” Sims says. “They make a great creamy base when you aren’t using traditionally creamy ingredients like milk and cheese, cream or yoghurt.”

The cake crust is formed from a course meal of almonds and dried dates, the ‘cream cheese’ little more than a thick, creamy milkshake of cashew butter with dates added for sweetness.

The butter turns firm when chilled, with a look and texture nearly identical to real cheesecake. The cold smoothness of the butter contrasts with the rough, nutty crust. The dates give a naturally measured taste of guilty sweetness. And the whole thing seems almost magical considering its list of ingredients.

Other cashew dishes include a raw key lime pie, a passionfruit cheesecake made with an almond crust, raw pizza made with Vegan cheese. There’s trail mix made with raisins and dried goji berries and just plain ol’ cashews available as well. But don’t let the healthy labels put you off. Most of the food is so delicious that you’d swear it must be bad for you.

WHO: Artillery, Michael Wild & Mekong Rain

WHAT: Meet The Makers, a see-and-taste photography and food series

WHERE: Artillery Cafe, Street 240½

WHEN: Until August 31

WHY: Food tastes better when you know where it comes from

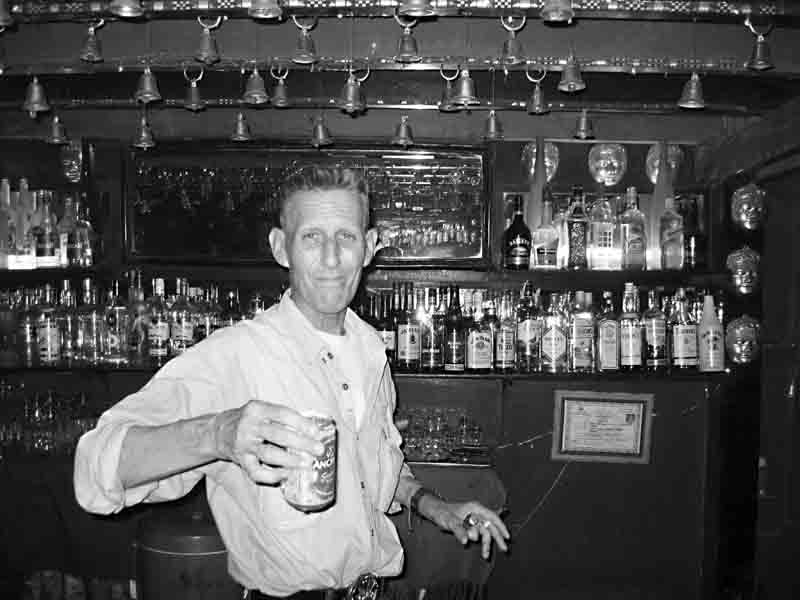

Ian Woodford, a throwback to the country’s bygone Untac era and a tall, wiry character whose colourful Australian language and endless Cambodian anecdotes were a cherished and longstanding part of Phnom Penh expatriate lore, died on May 23 in Sydney. He was 56.

The cause was complications following lung surgery, his daughter Maxine said.

In those heady Untac days, Phnom Penh was a town full of soldiers and mercenaries, chancers and grifters. Few would last; even fewer were worthy of keeping.

“I will always remember Snow as a fearless defender and supporter of anyone he considered a friend, which to my humble pleasure included me,” said Phnom Penh Post founder and fellow long-timer Michael Hayes, using the nickname by which Woodford was known. “Countless times in the last 20 years, when I’d see him somewhere along the riverfront or at his glorious, deliciously kitted-out oasis across the river, he would make a specific point of telling me that, first, he loved the Post and the stories we were running; second, that he admired what I was trying to do; and, third, that if I ever needed any help, no matter what kind or at whatever time of day or night, all I had to do was give him a call and he would be there – physically, in person, ready to do what was needed. And the thing with Snow that meant the most is that I knew what he was saying was a personal unwritten law among mates, not just some kind words thrown out in passing, but an eye-to-eye oath among kindred spirits.”

Born October 30, 1957, in Bega, New South Wales, Woodford grew up in Dundas, a suburb of Sydney. He moved to Phnom Penh in 1993, just as the United Nations Transitional Authority of Cambodia was winding down its $1.6 billion machine. Woodford found work as a contractor with a cowboy Australian outfit. His first job included working with Khmer Rouge soldiers in Ratanakiri, ensuring ‘safe passage’ of UN vehicles out of the province.

“It was just me and an American named Bob, who left after two trips,” Woodford told friend and fellow Australian Bronwyn Sloan in a 2008 interview. “It took five trips, 150 kilometres each way, at nine hours per trip, to deliver all the vehicles. Along the way, we regularly collected groups of Khmer Rouge, who would make us stop on secluded roads to drink homemade wine from plastic bags around the vehicles. Then they’d suddenly disappear into the jungle and we’d be off again. At Kratie, the UN helicopters would pick me up and take me back to Stung Treng to begin another convoy, but one night I got stuck in a Kratie hotel room with 31 Khmer Rouge soldiers because the choppers couldn’t land. I thought I was finished. When I returned, the UN soldiers looked at me very differently: they respected me… but they thought I was crazy.”

The UN left soon after, but Woodford stayed behind, enamoured with the Kingdom and its edgy, post-war disorder. He began teaching English at The American School, where he stayed for more than a decade. His reputation grew with each major news event, which, when at all possible, Woodford preferred to witness from the most dangerous vantage point available.

During the violent clashes of July 1997, Woodford and a few crazy-brave friends grabbed cold ones and roamed the streets searching for the ‘bang bang’. In the aftermath of national elections a year later, Woodford, cold beer in hand, ducked around trees and dived behind corners following the sounds of machine-gun-fire down Street 63.

“Whether it was about Islamic militants who were scouting the capital a decade ago or the constant political machinations of his commune, Snow’s knowledge and advice was as sound as it was welcomed, more so after a hot day with a cold beer,” said Luke Hunt, another long-time friend. “But what always struck me was the diversity in his character, a doting father who dabbled in the arts and ran one of the most celebrated bars in the country. Fleet footed, Snow also had the hands of a prize fighter, the soul of an artist and the heart of a lion: qualities which are often in short supply in this country.”

It was in 1997 Woodford rediscovered a childhood love of art, and in the small apartment he shared with his girlfriend Annie, he began drawing then painting in earnest. His only child, a daughter named Maxine, was born soon after in December 1999. Fatherhood turned Woodford from a fast-living thrill-seeker into a proud papa. As Maxine began to walk then run, the two left the capital for a quieter place on the Chroy Changvar peninsula, where Maxine could learn the joys of grass and trees.

In 2001, Woodford landed a small part in Matt Dillon’s City Of Ghosts. He played a drunk and belligerent foreigner in a red-light brothel. Roland Neveu, the film’s official photographer, captured the scene and a copy of the image still hangs in Cantina, one of Woodford’s regular watering holes. As Maxine reached school age, Woodford began to think better of Cambodia and in 2004 the pair returned to Australia, but neither one of them liked it much and they were back after only a few weeks.

In late 2005 Woodford opened Maxine’s Bar in a large, blue wooden house on the east side of the Tonle Sap River. It was as casual and quirky as he was. A table made from decommissioned AK-47s occupied centre room for a while. A thousand bells hung from the ceiling and when the wind blew they made beautiful music. More than one person thought it the best bar in Southeast Asia, maybe even the world. Dengue Fever played one of their earliest Cambodian shows there. National Geographic and celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain both used it for production settings.

Woodford worked Maxine’s at night and followed his passion of painting during the daytime. He worked in an aboriginal style of dot painting and filled the bar with his art: first portraits, then vases, masks and tables. Before long his art was fetching impressive sums and he finally gave up the day job. “I’ve always been decorative,” he told Sloan in 2008. “Even at school I always used to draw, but art was extra-curricular so I used to cop a lot of stick from the lads, teasing me and calling me a girl for wanting to paint. A lot of stick. But I have always loved things to be bright and vibrant and beautiful in any home I’ve ever had. This elephant lights up the room, doesn’t it?”

Just as things were starting to take off, a health crisis threw Woodford for a spinner. “I was sold some fake medicine [in 2007] by a clinic and before I knew it, it was touch and go whether I would make it or not. It took out my liver and part of my lungs.” He tried to continue painting, but the acrylic fumes were just too damaging to his lungs. In 2011 authorities told him he had to close the bar; the land was needed for drainage and road projects. Then the lung problems came roaring back and he and Maxine made a permanent move to Sydney.

Woodford endured two more major thoracic surgeries, he told friends over beers during what would be his final time in Phnom Penh late last year. Each time under the knife could have been his last, he said. They cut him open from the hip to the armpit. Twice. And he made it through both times, if just barely. Now he was back, if not 100%, at least well enough for some rest and relaxation. “The doctors cut me loose. They told me: ‘Take a vacation, mate. After all you’ve been through you deserve it.’”

“Excellent,” Snow replied. “I know right where I’m facking going, too.”

A local memorial service is planned for 9am Sunday June 1 at Wat Saravan.

(Photo: Bill Irwin)