Sharing the reservations of a rabbi and the fears of a caliph, I have always been suspicious of pigs. Perhaps it was from reading Animal Farm at a tender young age, when the concepts of metaphor and political analogy were still too complex to grasp. Instead, taking Orwell’s tale literally, I nurtured a secret fear that the swine down the bottom of the yard would break out of their sty, head up to the house and start mouthing things about the ‘rights of animals’, ‘four legs good’, while taking great chunks out of my father’s legs. Later, in my (un)gentleman farmer days, I had a Jack And The Beanstalk moment and inadvisably purchased two Captain Cooker pigs from a guy I met on the side of the road. Now these denizens of the porcine world are descendant from animals that the good Captain brought to the shores of Kiwi-land in the 1700s. Not enamoured with the whole 150-day boat voyage thing and despite the good Mr Cook releasing a few of them into the wild, they’ve held a grudge ever since, randomly coming out of the bush to maul hapless grannies putting out the morning washing. Now, my Captain Cookers never seemed to calm down from the ride in the back of the Hilux, stuck in a sack, and reiterated their displeasure through an ongoing campaign of escape and leg biting. They also refused to put on any weight, which meant they were never in a condition to be turned into something more wholesome. I eventually sold the ‘Terrible Twins’ to a polite and gentile couple from Utah who seemed pleased to be purchasing a genuine heritage breed, which was kind of true. So what this back story says is that I have sound grounds for my doubt about pigs, bacon, pork and ham. Unfortunately, however, I’m also a sucker for a name, so it was impossible to pass up an eating establishment named Taiwan Overload Pig Restaurant, which I recently discovered on Street 225. Advisorites, please note: this is my second review for a restaurant along this short stretch of road; I suggest you check this colourful street out soon before it’s discovered by hipsters (RIP, St. 240½). Nominally described as ‘Taiwanese Cuisine’, the Overload Pig Restaurant leans towards one central ingredient for its inspiration. It also seldom attracts native English-speakers: the entire menu is in Cantonese. Still, the pictures kind of approximated with what eventually arrived, so it was no trial to order and the staff seemed delighted to see us. We then sat back and were entertained by an energetic four-year-old who, at one point, needed convincing to not de-robe in the main restaurant (Lady Gaga and Miley Cyrus, you have a lot to answer for!). As for the food, despite my pig reservations, the dishes were excellent: a highlight being the braised pork with tofu and a steamed ensemble of leafy greens. The pork ‘cake’ from the menu, meanwhile, turned out to be schnitzel, which was more than OK by me. The spring onion pancakes and fried pumpkin croquettes ran a close third on the scrumptious-o-meter, although in a serious case of over reach, we proved unable to finish them all. The only let down was the accompanying rice, which my Japanese partner was sure wouldn’t pass muster back in Tokyo; still, the complimentary soup largely compensated for this disappointment. Bill time: $15 covered the lot for three of us, which was a bargain by my humble estimations. And so, duly overloaded, we stumbled out into the street, but I think it will only be a short time before I return again. As for the whole pig thing, perhaps I might get over that after all. Taiwan Overload Pig Restaurant, Street 225 & 122.

Byline: Wayne McCallum

Along In The Jungle With Wild Things

Errrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrqqqq…

A friend recently remarked that no matter where you are in Cambodia, someone will be using power tools. Add to this the Makita choir weddings, funerals or a plain old karaoke session, and it’s pretty hard to image a world that’s tranquil and natural.

Adrian Stoeger, self-proclaimed sonographer, is out to redress this with his release Sounds From The Cambodian Wild, available through Bandcamp. With sounds including gibbon calls, the cries of great hornbills, croaking frogs and the lapping of waves on the shores of Koh Thmei, Adrian’s recordings offer a natural respite from the Penh’s manufactured cacophony. The Advisor caught up with Adrian to ask him about the release, starting with the most obvious question:

What exactly is a sonographer?

Usually people going out with material to record sounds are called ‘field recordists’. However, this sounds too technical and most people can’t associate anything with the term, so by using ‘sonographer’, I’m hijacking a [medical] term in an attempt to place audio recordings in the same context as photography.

What attracted you to recording the Kingdom’s natural sounds?

What attracted me were simply Cambodia and its natural habitats. I am German, grew up in France and arrived in Phnom Penh from Berlin in 2011, where I had been working in the music industry for the last few years, but I was growing bored just working from my desk.

At one point a friend with Save Cambodia’s Wildlife asked me if I could help them to make a CD of recordings of Cambodia’s natural habitats. That led to a one-week expedition into the Virachey National Park and Cardamom Mountains. And that was it. I knew this was something I wanted to do.

Also, making nature recordings is a great reason to get out of the city and organise trips you’d never consider otherwise. How many people in Cambodia have spent several nights in the jungle, sleeping in hammocks and surrounded by the forest?

What field equipment do you use and what do you do with those sounds once you’ve captured them in the field?

I usually use an Audio-Technica shotgun microphone, which can record sounds from the front. Back at home I import everything into my computer and start listening. This is a very important part and often a great recording will be discarded because I can hear something in the distance; I simply don’t want any human sounds! Once I’ve identified a good sound, I then start working on it.

Ideally the sound will stand as it is and I will do nothing; sometimes I increase the overall volume a bit, but that’s it! I don’t add any effects, like reverb, for more space. The ambience of the forest is like it is.

How do you decide on the sounds you use? Do you go out seeking a sound, or simply use what you capture?

It’s very easy: the sound must be compelling, the quality of the recording must be impeccable and there must be no noise pollution from other sources, and there must be at least a few minutes of material. Also, the ‘feel’ of the recording is very important. I want people to enjoy listening to it, bringing nature closer to them. I will sometimes leave out cicada recordings that are interesting, but so loud and high-pitched most people wouldn’t enjoy them. That screens out about 90% of recordings.

Is there a ‘wild sound’ out there that you were compelled to capture?

There was. It took me three trips to Virachey to get the gibbons the way I wanted. Three trips to Ratanakiri for five minutes of gibbons! But hey, as far as I know, nobody has recorded them in this quality in Cambodia. Soon after I was staging a listening session at a Meta House. Afterwards a man came and told me that he simply couldn’t hold back, he had tears flowing while listening to the gibbon calls. These wonderful, endangered primates have made their voice heard – that’s the greatest satisfaction I can get.

Sounds From The Cambodian Wild is available for $7 at adrianstoeger.bandcamp.com. Get 25% off before September 13 by entering the code ‘advisor’ at checkout.

Thought control

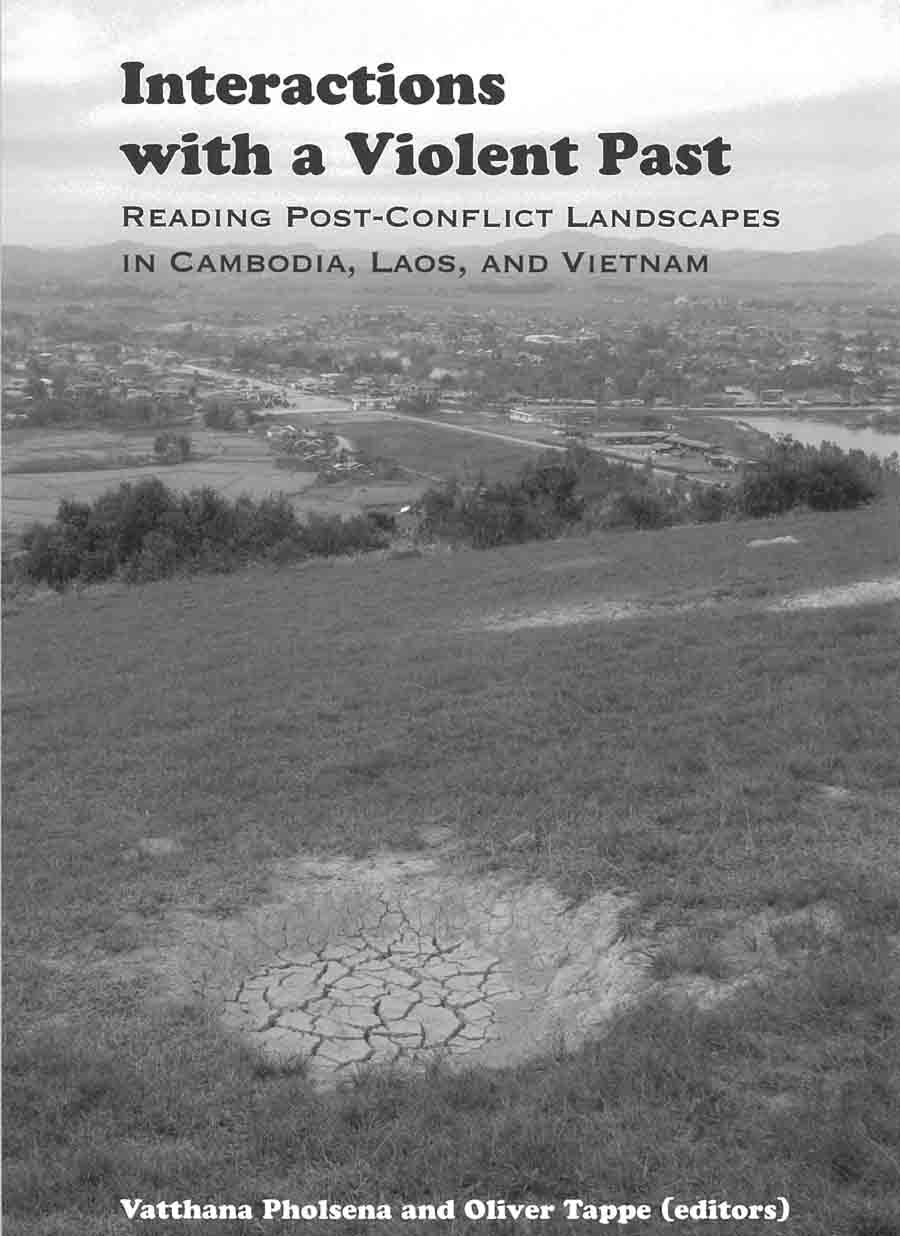

Stupa debates at Tuol Sleng, bomb-crater tours in Kampot, Agent Orange demonstrations in New Zealand; the Indo-Chinese wars (three and counting) may have been completed on the battlefield, but as Vatthana Pholsena and Oliver Tappe’s recent book Interactions With A Violent Past: Reading Post-Conflict Landscapes In Cambodia, Laos And Vietnam shows, conflict over interpretation continues to rage.

Exploring this through the vehicle of landscape, Interactions With A Violent Past brings together a series of studies that shows how meaning and power have contributed to multiple interpretations of the way the impacts of war are remembered in Indochina. Linking the studies is an interest in how these interpretations are expressed through memory, memorials, protest, performance and words, and the ways different groups vie for their representations to be accepted as the pervading understanding of history. These contests are, as the authors point out, inherently political, because the acceptance of one interpretation over others permits access to things as divergent as courts and compensation, while others find themselves excluded.

Unsurprisingly, this is an academic enterprise and Interactions is unlikely to appeal to those seeking some light beach-reading over the August break, with layered jargon (‘polyphonic memoryscapes’, ‘mneminic worlds’) and theories from people with long names persisting throughout the book. But for those seeking to exercise the grey matter, Interactions offers some nice rewards, while providing a whole new way of viewing the Kingdom and the wider Indochina region.

In terms of Cambodia-based research, the chapter by Sina Emde is especially insightful. In his study the author explores the roles of Tuol Sleng and Choeung Ek as memorial sites and the part played by the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) as a forum for the expression of memory. Emde starts with the argument that Tuol Sleng and Choeung Ek have evolved into economic enterprises that have commercialised the suffering of the past, while providing a distinct state interpretation of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge history.

As a rejoinder to this bleak interpretation, Emde shows how the testimony process for Case 001 (the trial of Duch, see Advisor, April 11 issue) has offered individuals the opportunity to assert their memories, both at the hearings themselves and during court visits to Tuol Sleng and Choeung Ek (a consequence of the ECCC process that has been seldom articulated elsewhere). Nevertheless, as Emde writes, the blurring and shifting lines between who were the victims and perpetrators make questions about how to record and remember the past at these sites complex and difficult.

This was demonstrated aptly in the recent debate over the intention to place the names of those who perished at Tuol Sleng on a stupa at the site. Those opposed to the proposal argued that doing so would result in people responsible for Khmer Rouge atrocities, and who were later killed at Tuol Sleng themselves, being recorded alongside those they had helped murder. It’s a deep argument, but through the vehicle of Emde’s research one is given a map to guide the way through the complexities of this and other memorialisation processes underway.

Other chapters feature the ‘landscapes’ of unexploded ordinance, Agent Orange protest, and the impacts of war-driven relocation on indigenous groups in Vietnam. Numerous plates, tables and maps are included in what is a well-presented set of studies, neatly woven together with a good summary introduction at the beginning of the book.

Interactions is one of those reads I describe as a ‘sleeper’: it sits on the shelf in the store and you hardly notice it’s even there, but when you do pick it up and start scanning its pages you receive a pleasant surprise. Give the research between its covers the attention it requires, but be aware: things will never look the same again.

Interactions With A Violent Past: Reading Post-Conflict Landscapes In Cambodia, Laos And Vietnam, edited by Vatthana Pholsena and Oliver Tappe, is now available from Monument Books for $36

Dish: K-food from the Seoul

Having written about South Korean music and waxed about its cinema, it was finally time to take the plunge and explore the neon-Kingdom’s cuisine, while seeking an answer to that immortal question: is there more to K-food than kimchi?

Before going further, a little context: at the heart of appreciating Korean cuisine is the understanding that unlike Japan, where food developed with little foreign influence until the late-1800s, Korea’s fare evolved from a combination of traditional agriculture and the contributions of occupying groups, including the nomadic tribes of Mongolia and the conquering armies of China and Japan. Despite this the Korean diet has remained centred on three core food groups – rice, vegetables and meat – with each colonising force adding its own influence.

For my journey of discovery I enlisted a Korean friend and gave him some clear instructions. First up, I wanted to go to a place where, when I shut my eyes and tasted the food, I was transport to the neon-lit heartland of Seoul. Next, I wanted something that was not over-the-top expensive, a bane that strikes a number of South Korean establishments in the Penh. Finally, ever the bike peddler, I wanted something that was central and not out in the boondocks. “Easy,” my epicurean guide replied. “Jaru on Street 225.”

It’s 7:30pm on a Sunday evening and I’m seated at Jaru, a mere stone’s throw from the Royal University of Phnom Penh. Already the table is covered with small dishes and we haven’t even ordered yet. My guide, seeing the doubt on my face (“What? Where did this come from?”), tells me these are appetisers that traditionally accompany the beginning of a meal in Korea. When in Seoul…

Looking beyond the starters I decide on Jaru’s full dine-set ($8) to get the full K-food experience. Two things are soon clear. First, it’s habit for most of the food to arrive in one wave and very quickly our table is brimming with plates and it’s difficult to find a space for our drinks (sadly there’s no Korean beer here). Second is that while portions are numerous, servings are small. This emphasis on side dishes, banchan in Korean, is a defining feature of the nation’s cuisine with the various foods intended to complement the main serving of rice.

Now I may know my Super Junior from my Big Bang, but I’m struggling to work out the parentage of some of the food set out before me. There is kimchi, of course: fermented cabbage which manages to be spicy and sour in the same bite. There’s also a fried fish: small but extremely tasty, it’s called ‘croaker’ and has to be imported from marine farms back in Korea.

Close runner-up are three strips of fried pork belly. Nicely seasoned, like the fish they’re big on taste but small on plate-size. Some marinated mushrooms (I have to ask my friend what they are) provide the Korean equivalent of ‘If you don’t eat your greens, you get no dessert.’ Next up is a dish of grilled marinated beef known in Korean as bulgogi and which regularly graces Top 50 lists for the planet’s most delicious foods. I’ve been dying to see what the fuss is about and am pleased to report the Jaru version is well seasoned and perfectly cooked.

For the penultimate treat we’re served soup, which arrives on a sizzling hot plate. The presence of fermented soya-bean base, know in Korea as doenjan, gives the soup its name and results in a dish that resembles miso in taste. However, this is an altogether more exciting fare than the Japanese variety: added to the mix are minced pork, zucchini, onion, potato, chillies and capsicum. It’s a ‘miso stew’ – and it’s outstanding.

Finally, as all good journeys should, we finish with a drink: another Korean treat know as sujeonggwa and featuring a brown-coloured punch that includes ginger, cinnamon and dried persimmon. The punch is sweet and spicy and is served, so I’m told, to aid digestion. Like the fish, pork belly and doenjan, it’s another highlight.

So how did we fare? On taste, price and accessibility, Jaru fulfilled all of my criteria. Other things such as décor and service weren’t overstated, with the bright lights and stark surfaces characterising some Korean establishments thankfully absent. Neither bold nor flash, Jaru understands what it’s about and delivers with a confidence that requires no bells or whistles: it’s good and it knows it.

Jaru, #35 Street 225; 023 885665.

K-pop u don’t stop

In 1281, Kublai Khan set his sights on conquering Japan. His Mongol army had already made it to the gates of Vienna, occupying China, Korea and much of central Asia along the way. Mobilising a massive fleet Kublai set sail for Fukuoka, in southern Japan, vowing to defeat the nation. The Japanese, although vastly outnumbered, smashed the Khan’s fleet with a little help from a certain ‘wind’ (the Kamikaze). The defeat remains the greatest naval disaster in history.

On a warm spring evening not so long ago, nine young women from Korea launched their own assault on Fukuoka. The city offered little resistance and politely threw open its gates. After two bars of Motorcycle, their opening song, the surrender was complete. Victory total. Kublai Khan was a pussy!

Wharf-side, Fukuoka: Two hours before the show and the area outside the Marine Messe stadium is packed to the gunnels. People are gathered around the merchandise booths, keen to mark the date with a memento – a T-shirt, poster, even perfume. Groups of young (and not so young) Japanese are sitting down, texting, taking photos, recording movies and updating their Facebook pages.

One spot has drawn a particularly large crowd. In the centre are nine fit and slender Japanese women, dressed and made-up like the artists we’ve come to see. They complete the exact moves of the band’s most popular songs and draw a massive ovation from a fawning crowd. People rush up to have their photos taken with the group and there’s soon a long queue. Another tribute act is working hard to draw an audience; they complete a song and receive a sympathetic clap from a small group of semi-interested watchers, their thunder well and truly stolen by the competition.

Tonight we all have tickets for the hottest band in K-pop: Girls’ Generation. They’ve sold millions of albums and singles, featured in some of the most iconic videos of the K-pop era (Gee, Genie, Mr Taxi), appeared on Letterman and even graced the hallowed pages of The New Yorker. They are as close as you get to K-pop royalty – the Beatles of K-pop – and their Japanese fans, all 20,000 here tonight, just can’t get enough.

Misaki and Yui are at design school. They’ve both seen Girls’ Generation perform before but wouldn’t miss this concert for the world. Yui: “I like Girls’ Generation because they are normal girls. They eat and behave well.” Misaki: “I really want to visit Korea, maybe see our idols.” Seated beside them, Ymi, a Girls’ Generation towel around her neck, shows me some of the merchandise that she has purchased. “I have spent ¥ 40,000 [$400], including the ticket.” Aoi, another friend, confesses she has spent even more.

Further along I spy two young men talking. Kohei, the tallest, attends a local university and is completing a degree in management. He tells me he’s been following Girls’ Generation for four years and also likes the band T-ara and the artist IU. And how do the Korean bands compare to those in Japan? “The dancing level is quite a bit higher,” he confesses. Riko, his classmate, agrees. “Japan bands like AKB 48 are cute, but Korean bands have style and seem sophisticated.” How about their look? “Oh, yes” he laughs. “They are sexier.”

In the Penh, the K-pop brand is everywhere, from music and clothes to social media, so where did all this come from? And what is K-pop? What drives it? And is there really more to it than Psy and ‘that song’? From wharf side Fukuoka to the riverside of Phnom Penh, The Advisor is on the case.

Riverside, Phnom Penh: It’s twilight on a muggy June evening and five rows of young and beyond young Khmers are exercising in the fading light to music thundering out of an antiquated sound system. For now the rain has stayed away and some of the participants look to be building up a sweat. The speakers bellow out a distorted version of 2NE1’s I Am the Best, the band’s most popular song. Arguably the most adventurous of the current crop of K-pop bands (the Rolling Stones of K-pop?) they’ve made a strong push for the US market, performing with the likes of Snoop Dogg. Further east along the river, Koh Pich has played host to several second division K-pop bands over the last few months, including T-ara, Sistar, Tahiti and Miss-A. Four blocks back, on Street 19, the ‘cool young things’ that staff the street’s 8000r hairdressing shops are trying to emulate the styles of their K-pop idols. On the walls are scattered the posters of numerous K-pop boy bands – Super Junior, SHINee, CNBlue. A speaker spurts out Adele’s Heaven, while beside it a hairdresser is carefully running wax through his hair, trying to exact a Jay Park look sans tattoos.

The Music Factory:

“There is something distinct and special about K-pop. It’s like everything is a little bit louder, the images brighter, the style flashier – it’s just more.” – Mark Russell, author of K-Pop Now!

K-pop is pop music produced in South Korea, but it’s more than the music we know and consume in the West. It’s a neon-lit, ultra-modern, sophisticated and stylish interpretation of what pop music can be; a mash-up, borne from the collision of corporate Korea and the broadband consumer culture of East Asian youth. Welcome to the ‘music factory’.

At the centre of K-pop lies a group of independent music agencies modeled on the family corporate structure that fueled Korea’s post-war recovery. The companies control every aspect of the performer’s professional life and a good deal of their private. Artists are typically recruited in their young teens, through talent competitions or auditions, and then inserted into the company’s K-pop machine. What follows are years spent at school, learning English, Japanese and Chinese and then reporting after class for training – modelling, acting, dancing, singing, media coaching – before returning to company accommodation to complete homework. Fourteen-hour days are not uncommon and the process is demanding; some of Girls’ Generation trained for seven years before they finally took to the stage with the band. Others fall and fail and are spat out by the music machine.

The notion of music as a corporate product is not unique to Korea. The Beatles, for a time, were part of a production factory held together by Brian Epstein and dubbed ‘Mersey Beat’. Detroit’s Motown and Memphis’ Stax were all companies that applied a factory concept to music production, creating a distinct sound and then milking it for what it was worth. Also the phenomenon of music waves emerging from different countries of East Asia is hardly new either. In the 1990s J-pop, from Japan, was the rage while further back, in the early 1970s, artists such as Teresa Teng surfaced from Taiwan and became fashionable across the eastern Pacific. But what has distinguished K-pop from these movements has been the effort to go beyond the ‘song’.

Beyond the song:

Past the language, few who listen to K-pop would notice anything different from a conventional American or European song. Hip-hop, Euro-pop choruses, dub-breaks and some rudimentary rapping are all represented, but in K-pop the song is only the beginning. Around the tune are built elaborate choreographed performances, some now as iconic as the songs themselves. The Girls’ Generation ‘kick flick’ is synonymous with their tune Genie, while the body flips that feature in Got 7’s recent hit Girls, Girls, Girls have gained celebrity status.

Then there are the videos. For many westerners this has become the gateway to K-pop and it was Psy’s Gangnam Style that sent K-pop viral. Here, music collides with the production values and techniques of the nation’s burgeoning film industry. The result: videos that may not make much sense, sometimes verging on the bizarre, but are always enticing.

In Cambodia, K-pop has been especially well served by the internet and the nation’s netizens are renowned for the amount they ‘share’ about their K-pop idols, giving agencies an enormous opportunity to expand the commercial reach of their performers. In reality this translates into a cycle of commercials, endorsements, acting roles and weekly appearances on talent and game shows. The members of Girls’ Generation have endorsed everything from Domino’s pizza and rechargeable batteries to banana milk.

Going global?

Visibility is crucial to success: the Achilles Heel of K-pop as it seeks to expand into Europe and the US. Spend too long overseas trying to ‘break through’ and run the risk of losing your audience back in South Korea: one of the reasons Japan, China and wider East Asia, including Cambodia, are so attractive. Bands such as Girls Generation and Super Junior can easily pack-out a 30,000 venue in Tokyo or Hong Kong one evening and be live on a domestic game show the next afternoon.

Many bands like Girls Generation and Sistar feature sub-groups (Twinkle and Sistar 19 respectively). Artists perform English, Chinese and Japanese versions of their songs to make them marketable in other countries. The boy band EXO takes things one step further and has two versions of itself: Chinese (EXO-M) and Korean (EXO-K). They perform the same set, but in two different languages.

All of this makes the 2012 success of Psy (real name Park Jae-san) and ‘that song’ all the more remarkable. Neither young nor beautiful, in a traditional K-pop sense, the man achieved international success with Gangnam Style through the viral, organic power of the internet. Nor did the song’s video feature the sophisticated dance moves that popularise K-pop. Instead, Psy made his mark doing the ‘air horse’. Around all this he wrapped words and images that poked playful fun at elitist attitudes within Korean society. In short, Psy took the piss and in the process the most unK-pop of artists became its poster bloke and figurehead. Ultimately, it’s this spirit of irreverence and fun that makes K-pop palatable to a wider international audience. Depressed by global warming? Watch SHINee’s Replay. Got the post-GFC blues? Take in 3.55 minutes of Sistar’s What Should I Do.

Wharf-side, Fukuoka:

9pm and Girls’ Generation are about to perform Stay Girls, their final number. Seven costume changes, 28 songs, a healthy dose of auto-tune and an impressive array of computer graphics, yet the girls haven’t broken a sweat. One word captures the feeling in the stadium right now: love. You can feel it everywhere: the adulation of the audience, the gratitude from the performers (expressed in perfect Japanese). I want to bottle this spirit up and pour it over some militant Islamic types or pro-gun lobbyists and then ask them to do the line dance from I Got A Boy. Yet in truth the K-pop high-water mark may well have passed and the chances of Girls’ Generation or anyone else emulating Psy’s success are unknown. For many, the legacy of K-pop will remain Gangnam Style and drunken office-party depictions of the ‘air horse’.

But tonight this means nothing. Tonight it is all about ‘now’ and right now we are in love with Girls’ Generation.

Rosette Sok, a Cambodian teenager from Touk Kork, shares her thoughts on the popularity of K-pop in the Kingdom:

K-pop seems to have a strong influence on the music and fashion of young Khmers. Why do you think it’s so popular in Cambodia?

It’s the image, I think. The Korean culture places quite a strong emphasis on beauty and being beautiful and in most K-pop groups there will be at least one or two members who are deemed to be the ‘visuals’ – the face of the group. These idols dress and look the way many ordinary people can only dream of, so while their talent plays a very large part in the rise of their popularity, it is also very much linked to their image.

What do you like about K-pop?

First, the music is unique. With the music comes the presentation of it: K-pop music videos are unlike English music videos. There is a lot more emphasis on dance, more so than depicting a storyline. Secondly, the members: people around the world think they’re good-looking, which is largely the reason it’s so popular. While girl groups are very well known, it’s the boy bands that generally have more fans. A lot of boy bands have many members – with more members comes more fans, because with so many members, there will be at least one who will be closest to a fan’s ideal type. It sounds very shallow to like a band for their looks, but it’s honestly the truth. The music gets you started with K-pop, but what really gets you hooked is the image of the artists.

Who are your favourite K-pop idols?

Exo, who are probably one of the most successful boy bands in South Korea. They were the first K-pop band I listened to. I like them the most because of their sound and their image is very distinctive.

How does K-pop affect how you think about South Korea?

I was in South Korea two weeks ago with my best friend for our graduation trip. I was the one that suggested South Korea back in February, which was around the time that I started to really get into K-pop. I believe that K-pop and the image that people associate with it completely changes one’s perspective about South Korea, especially among youth. I was never interested in visiting South Korea until I got into K-pop. I think if I hadn’t become a fan, I wouldn’t have gone to South Korea last month, nor would I have decided to go anytime soon.

And K-pop’s long-term future?

It’s evident K-pop is rising. On an international level, it has incredible potential. It’s reaching people from all over the world, from different backgrounds and fan bases. It is growing. It’s not just in South Korea anymore; it has impact everywhere!

In Phnom Penh, how do you get to experience K-pop?

When you go to South Korea you experience K-pop in subways, in restaurants, in malls; it’s everywhere you go. It’s not to the same degree here; some of the only ways to experience it are through your group of friends or through social media. There have recently been more channels on TV that play Korean dramas, reality shows and K-pop. The Korean influence is definitely more prominent now, compared to in previous years, and it will continue to grow. With that growth, more ways to experience the Korean entertainment industry will follow.

One last curtain call

The name Finale seems a strange title for a book dedicated to the funeral of King Norodom Sihanouk (1922 – 2012). But then again looking back at his life he was a man who embraced the theatrical, who thrived on being centre stage, so maybe the title is appropriate after all: a man taking a final curtain call on a life lived large.

And what a life! Chosen to be king in 1941 by the Vichy French, who considered him ideal because of his seemingly singular interest in girls, horses and cinema. A figure who confounded these expectations by skillfully and shrewdly achieving independence for Cambodia a mere 12 years later, an outcome that took Vietnam a further 22 years to achieve and the countless loss of lives. A man who then presided over a golden age of development that encompassed the arts, architecture and public infrastructure, while holding off the Cold War forces that were tearing the rest of the region apart.

An individual who abdicated not once, but twice and who again, twice, sided with the genocidal and decidedly anti-monarchist Khmer Rouge, the same regime that murdered countless numbers of his relatives and friends. And then, in the post-Untac years, who slowly sunk from view as craftier politicians edged him from centre stage.

The King Father was nothing if not a complex, even flawed figure, who nevertheless inspired an incredible reverence in the hearts of Cambodians. Put simply, the likes of him will likely never be seen again on the Cambodian stage. And like many who had arrived in Cambodia in more recent times I was taken aback by the enormity of the outpouring of grief and devotion that came with the return of Norodom Sihanouk’s coffin to Phnom Penh on October 17, 2012. What followed was a carefully choreographed funeral ‘event’ that unfolded across the weeks and months through to February 2013. And it is these events that Jim Mizerski’s book seeks to recount and explain.

Well, sort of.

Finding no up-to-date guides of the funeral ceremonies for Cambodia royalty Mizerski relies on translated records of prior services to illuminate our understanding of King Sihanouk’s funeral. This explains why the book’s title references two Norodoms in its heading. The assumption here is that the consistency of custom and rituals should carry over from the past and into the present.

What we get in Finale, therefore, is not a careful rundown the King Father’s funeral but a ‘funeral by association’, with detail drawn from translations of the description from funeral rituals that accompanied the death of a previous King Norodom, although one who died sometime back in 1904.

Hmmm. It’s an interesting assumption and because I was not around in 1904 (at least not in this life) I’m not in a position to offer a contrary view, so I think we have to take Mr Mizerski’s approach at face value.

Thankfully, for those who might become confused by this move, Finale’s photographs are up to date and provide a comprehensive record of events across the different ceremonial stages of Sihanouk’s funeral.

Regrettably, just as we are deprived of an up-to-date account of the ceremony, we are also deprived of the drama and intrigue that occurred beneath the surface of King Norodom Sihanouk’s funeral. This includes the efforts of the PTB (the ‘Powers That Be’) to capture the public emotion unleashed by his death to polish their own reputations. What this means is that we get a ‘manual’ and no Shakespeare.

As a consequence, anthropologists, historians and ethnographers are likely to be the most pleased with Finale, while the rest of us will find better mementos in our personal memories of those days. A time where, rather than being solemn, the air seemed to be positively charged by human emotion, feelings that could not be controlled or marshaled by any single cliché; an energy, I think, that ultimately inspired decisions made at the ballot box a few months later.

So what are my memories? Two stand out.

The first is being on a deserted waterfront, the road shut from traffic for the funeral parade, all shops closed and shuttered; there being no one else in view except two confused-looking Chinese men wheeling their suitcases down the middle of an empty road.

The second, watching the King Father’s funeral carriage pass and kneeling, together with everyone else, to show my respects. Then seeking to get up but being told by some green-clad military types to kneel back down for the carriage carrying the PTB, and the look of ‘You have got to be joking’ on the faces of the people around me, refusing to kneel and everyone smiling and laughing. And somewhere up there, I think the King Father would have been smiling, too.

Finale: The Royal Cremations of Norodom and Norodom Sihanouk, Kings of Cambodia, by Jim Mizerski, is available for $7 at Monument Books.

Where Waters Flow

Author Gea Wijers asks: Why do so many Cambodian-Americans chose the NGO path as part of their reintegration strategy, while returnees from France seek to work within the Cambodian government?

“In my experience, your life is like a log floating down the river where the flood was taking place. You just go with the flow. You have to navigate by what you can see. You have to navigate a river by its bends.”

– Cambodian-American returnee

Two days ago I had a mind-jarring, sweat-inducing flashback. No, I wasn’t being jammed into a 4x2ft locker by the strapping, laughing boys of my old fifth-form school, me a hapless and as it turned out very malleable third-former.

And no, I wasn’t playing on the wing of the local rugby club’s 10th 15 team (the Siberia of rugby positions in the Gulag of teams, reserved for those for who the gap between ability and enthusiasm was about as wide as the Mekong), with the ‘son of Jonah Lomu’ looming down on me like a bulldozer on meth.

No, the cause of my view into the rear-vision mirror of life was Gea Wijers recently published book Navigating A River By Its Bends. You see, no matter how interesting and informative Ms Wijers new book, one cannot escape the fact that, beyond the bright cover, the whole thing is styled and written in the form of the PhD study that her book is based on. And as a man who closeted himself in a room for five years working on his own doctoral mishmash, I’m not convinced this is a world of literature I wish to reintegrate myself with anytime soon.

And this, as it turns out, is a bit of a shame, because if you can go beyond the issue of presentation and language, Navigating A River By Its Bends is actually a damn interesting read. It’s just not the most attractive or accessible format by which to enter into the author’s topic.

Beyond these misgivings, what’s the book actually about? Subtitled A Comparison Of Cambodian Remigration, the book sets out to explore the strategies that American-Cambodian and French-Cambodian returnees employ to reintegrate into Cambodian society and some of the social and institutional challenges they face in their efforts to accomplish this.

Behind this focus is the research question that originally inspired the author, namely: why do so many Cambodian-Americans, upon their return to Cambodia, chose to establish NGOs as part of their reintegration strategy, while those from France seek to work within the Cambodian government (like me, you probably know returnees from both countries who fit neither of these categories, which suggests that Wijers question is more of a generalisation than a normative reality)?

Given this premise Wijers uses the theoretical lenses of entrepreneurship and social capital to drill deep down to explore the worlds of returnee integration. After all the ensuing data collection and analysis, what emerges is a picture of how complex and challenging it is for returnees to shape their new lives and find new opportunities in the Kingdom; a challenge that persists despite the range of skills and experiences they bring back with them.

Driving this challenge, Wijers suggests, are elements of suspicion, social legitimacy, trust, acceptance and understanding (among other things), which conspire to thwart the capacity of returnees to become positive change agents in their ‘new’ home. Moreover, as the ties with their former country evaporate and the challenges of establishing new ones in Cambodia persist, many returnees experience feelings of exclusion and alienation.

By illuminating these processes, Wijers offers an appreciation of the implications for the parties involved, including the ‘lost opportunities’ for Cambodia – denied the full potential of the human capital that the returnees have to offer. And the personal frustrations of the returnees themselves, many who return to the Kingdom with high hopes and aspirations only to find them stymied by walls of social and institutional resistance.

Unsurprising, what this means is that Navigating A River By Its Bends is likely to have genuine appeal to those working in the subject area or who have a broad interest in the humanities as they relate to Cambodian society. Meanwhile, for those who come with a more casual attitude toward the topic, be prepared for a solid mental workout.

Whatever decision you make, just don’t expect any pictures.

Navigating A River By Its Bends: A Comparison Of Cambodian Remigration, by Gea Wijers, is available from Monument Books for $39.50.

From beer to eternity

Damn the French, with all their culture, subtitled films, good-looking rugby players called Jacques and fine wines. Why can’t we beer-imbibing Anglos claim some higher ground with our beverage of choice and engage in a tête-à-tête about the ancestry of the drink we shared over dinner?

Yes, there’s more to life than fine grapes! Where are the beer sommeliers out there, with their richly crafted metaphors about the brown lager at their table, the rippling pilsner on their tongue and the tasty ale they just spilt on the carpet?

Although in a country where some of the favourite tipples are named after a) felines; b) a large religious ruin; or c) part of a boat, I can understand the low visibility, but now we are fighting back! Not only that, we are even getting all philanthropic about it.

Yes, the craft beer company Cerevisia Brewery and their non-profit line, One River Brewing, is hitting the taps and fridges of CharmingVille and we ‘hopsters’ are excited.

But first, what qualifications does this Scribe of Street 130 have to pen in the heady world of ‘beer appreciation’? As a mixed-bred Anglo of Kiwi persuasion, I come from a country where our early European settlers are rumoured to have put beer in their breakfast porridge. And with the explosion of craft beers throughout the ‘land of the long, white cloud’ (soon to be rebranded ‘land of the long, pale beer froth’), I think my credentials are clear. Yes, it is in my blood, my veins run brown and I really am the lush – sorry, ‘man’ – for the job.

So bring on the ale!

My recent encounter with the amber liquid of Cerevisia/One River Brew began promisingly, as the smell of rich fermenting hops greeted me at the door of their newish fandango brewery. Less a backyard operation, these ‘hop heads’ – Erich and ‘Mr Brew’ – are more front-room guys, with a good portion of the latter’s downstairs house transformed into Brew Station Central.

Here, in this space, they strive to create what Phnom Penh has been crying out for (well, a certain apartment in Street 130, at least): quality pale, red and brown ales. Yes, in the Kingdom of Lager we have truly been missing something that harks back to those curry accompanying brews of the Old Country.

Underpinning the entire operation, states Erich – the head business honcho – is a desire to create “community”. Beer, he points out, “brings people together, in good times and in the bad”. Further, through their non-profit line, the business is trying to ensure their product benefits communities that don’t necessarily enjoy ale with their rice. “Our non-profit beer works like this: we will provide it, at cost, to places that wish to stock it and they will then be expected to donate any profit that they make to a not-for-profit organisation of their choice.”

Philanthropy and beer: perfect! But what about the commercial side of the operation? Erich: “We are on tap at Deco and The Exchange, and soon to be at Brooklyn Pizza and Chinese House, while bottled versions of the company’s beer are also on their way.” At a heady alcohol rating around 5.6 %, I’m keen to learn from Mr Brew the secrets to creating good ale. Cerevisia and One River Brewing’s resident beerologist is forthright with his reply: “Brewing and fermentation, conditioning, how you store it and the way it is drunk: they are all important.”

Geometry, apparently, is especially significant. Mr Brew again: “The shape of what beer is stored in during the different stages of the brewing process will have a big impact on the final taste.” So there’s more to it than cracking a tinny? “Definitely!”

There is undeniable fine science here – take that, grape-drinking folk – and while we may not be talking about the Higgs Boson here, to be frank, a dose of dark matter is not what I crave after a workout at the gym.

And, apparently, there is also history. “Recipes for beer date back to the Sumerian Empire and Babylon, even predating those for bread,” notes Mr Brew. Excellent! At last: historic validation for buying a six pack and forgetting the bread.

Vintage Asia Heaven

estampe (French) n. print, engrave

I thought I had died and gone to heaven. The source of my out-of-body experience was a visit to Estampe, a recently established emporium on Street 174, situated right next door to the equally heavenly Romdeng restaurant. Estampe pays homage to what its owner, Lien Bouvet, calls “Vintage Asia”, with originals and reproductions of maps, books, posters, magazines and assorted miscellany from the region’s Indochinese past.

Experience wise, Lien and her husband are no novices when it comes to capturing the essence of this period. In the mid-2000s they transformed an old colonial house in Battambang into the city’s premier boutique accommodation option, La Villa. Along with other projects, the Bouvets have amassed an impressive collection of antiques, which now serves as the base for Estampe’s collection.

Lien is quick to point out they are not selling their collection, they simply wish to share it: “Over the last ten years we have moved eight times! Each time we have had to pack everything up. It has become quite tiring. We also came to realise that we had several copies of different things, so it makes sense to sell these now. For the things we have only one copy of, we can make reproductions.”

Of the original items in the store it is the enormous range of maps that makes an immediate impression on entering the store. The breath of the collection is striking – as are some of the prices – and as a map aficionado myself I can’t help being envious of some of the editions the Bouvets have acquired.

One map, from the late 1800s, features Siem Reap and Battambang firmly ensconced in ‘Siam’ (‘Thailand’). Another map depicts the three separate sub-states that once comprised French-administered Vietnam.

Lien, quite rightly, is coy about where they have sourced their collection but remarks that it includes contributions, not only from Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos, but from further afield in France and the United States. “But it is getting harder to find things, and they are becoming more expensive.”

Still there are bargains to be had. A stylish vintage-inspired (as opposed to straight ‘vintage’, just to be clear) fridge magnet will set you back a mere $2, while a range of elegant period-enthused notebooks are equally economically priced at $7. But the merchandise is only half the reason for making the journey to Estampe.

The shop itself has been artfully renovated and outfitted to suit the mood of its collateral. Exposed bricks, fine-grained wooden window frames and a set of ceiling fans, rescued from an old Saigon cinema, create an ambiance that merges the stylish with the ‘feel’ of the store’s merchandise. This creates an impression of a retail space that is ‘curated’ rather than ‘stocked’.

And there is yet more to come, promises Lien. “We have more books, movie posters and postcard collections, which we plan to stock in the coming weeks.”

So if you are more of a Chinese House than a Public House sort of guy, and less a Sofitel and more a Raffles kind of girl, and you wouldn’t be seen dead in a late-model BMW but crave a 1930s Citroën TA, well then Estampe could well be your heaven, too.

Estampe, #72c Street 174; 012 826186 (open Monday – Saturday, 10am – 7pm)

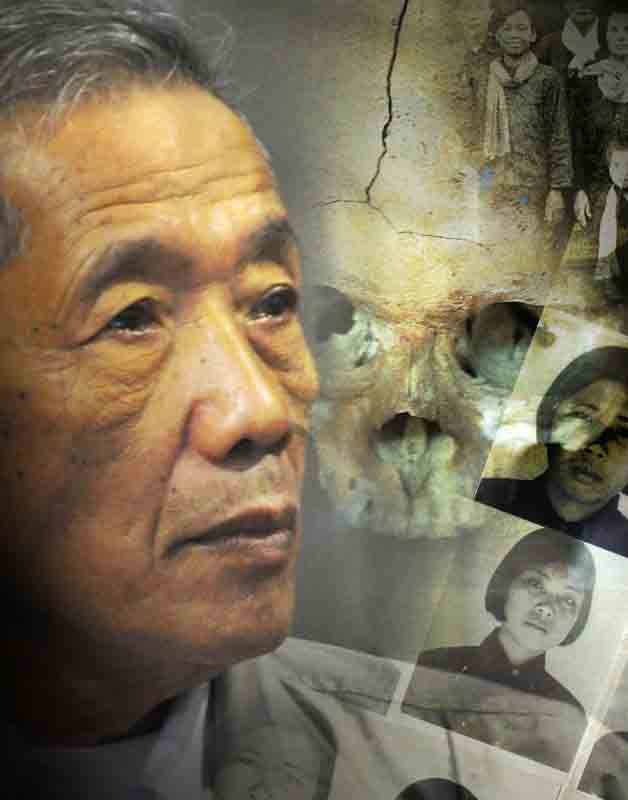

Victim of history

Thierry Cruvellier, author of Master of Confessions: The Making Of

A Khmer Rouge Torturer, examines an engima

He was born in 1942 in the small rural village of Choyaot, in the populous rice belt province of Kampong Thom, where his parents gave him the name Kaing Guek Eav. In his teenage years he was considered a model student, excelling at mathematics. Surviving photographs of the teenage Kaing show an attentive, even attractive, youth. A high hairline, raised eyebrows, the hint the person staring out at you might be a tad serious, but nonetheless a face that beams with hope and possibility.

Contrast this image with the thousands of photographs discovered in the files of S-21 (Tuol Sleng), the former interrogation centre and ‘ground zero’ for the horrors committed by the Khmer Rouge. Here, captured human faces leave us with a starkly different impression. Haunted, exhausted, confused, bewildered, they stare out in black and white with expressions of evaporating hope.

In 2012 Kaing Guek Eav, or ‘Duch’ as he was known by his fellow revolutionaries, was convicted by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) for crimes against humanity, murder and torture committed while director of S-21. Duch had admitted his guilt prior to the trial, stating several times that like an “elephant carcass” he could not hide his past “under a rice basket”. As such, his trial was a matter of determining what he was guilty of and the form of his sentence.

The journey that brought Duch to this point is an extraordinary one and a story central to the new edition of Thierry Cruvellier’s 2011 book, Master of Confessions: The Making of a Khmer Rouge Torturer. A seasoned journalist whose reportage has taken him to international criminal courts in Rwanda, Sierra-Leone and the former republics of Yugoslavia, Cruvellier is an ideal guide along this long and complicated path.

Eloquently written, artful and insightful – sometimes even amusing – Cruvellier’s volume does a persuasive job of bringing the many threads of Duch’s past, his trial and the tales of countless others (victims, survivors, colleagues, expert witnesses, legal counsels) together, keeping the reader mesmerised. The result is a book that reads like a novel, but never compromises the memories of the people captured between its pages.

Underpinning it is the captivating question: how did this man, a star pupil, transform into Duch, the Khmer Rouge pariah? Furthermore, we’re challenged to consider whether such a definition is overly simplistic given the events, personalities and politics that dissect his story. Significantly, Cruvellier also identifies other opportunities rendered by the retracing of Duch’s journey. This includes the capacity, drawing on evidence from the trial’s testimonies and victim statements, to drill deep into unanswered questions about the Khmer Rouge. More subtly, the author compels the reader to think about what Duch’s case means in terms ‘justice’ and, less comfortably, what his actions reveal about the human capacity to commit unspeakable acts.

I caught-up with Thierry, a native of France but currently completing a book tour in the US, to ask him about the arguments, ideas and themes raised by Master. Starting with the most obvious question, what drew him to Duch’s trial in the first place? “I had been covering war crimes trials since1997 when in 2007 I was asked to come to Phnom Penh to help train Cambodian – or Cambodia-based – journalists to cover the upcoming Khmer Rouge trials. I realised then that the Duch trial was going to be a unique opportunity to get the voice of the perpetrator, due to the fact that, firstly, Duch was essentially pleading guilty.

“Secondly, the civil law system that applied before the ECCC allowed a full trial, as opposed to other international tribunals where guilty pleas result in an agreement between the prosecutor and the accused, ending up in a one-day public hearing. This made me decide to stay and cover this trial in particular.”

Reading Master of Confessions, it struck me there was no one, single Duch. I wrote down some of the words that sprung up to describe him: bureaucrat, remorseful, impassive, emotional, survivor, pragmatic, denier, scapegoat, reverent, heartless, maleficent, even ‘victim’. When the author thinks about the Duch he saw, what were the words that described him best?

“I have never thought about putting all these words together. What strikes me is how much it shows how complex and rich his personality is, which is what made the trial so extraordinary and eventful. His multi-faceted personality offered an unusual entry into the process through which one can become Duch and into how one lives with it once the criminal period of one’s life is over.

“Because he spoke so much and tried to explain himself or the situations he was in, he was probably less of an enigma at the end of the trial, but there are always aspects of him and of his choices that only he knows. What’s interesting is to consider all aspects of his personality and accept that he may have changed from time to time, but if I try to answer your question more simply, perhaps ‘believer’ comes to my mind, and ‘survivor’ in a sense that he has a very strong sense of survival.”

In another time and place, it strikes me that Duch would have made a great Wal-Mart manager, which raises the question: does Cruvellier think he was a strictly a product of the context he found himself in or was there an element of free will to his actions? “It’s hard to give a one-sided answer. In the book there is a clear reminder, from the psychologist expert I think, that Duch was not born a mass murderer. These crimes are political by essence and they are the product of particular historical circumstances in which those who commit the crimes are caught or participate in, or both.

“Yes, Duch is the product of a particular place at a particular time in history. And yes, in other circumstances, he would have been a great educationist perhaps. He was, by all accounts, a good and devoted teacher who believed in education. I smiled at the idea of imagining him as a Wal-Mart manager, but to be honest I don’t think that’s what he would have been; he was always interested in ideas.

“The element of free will is more complicated. At some point Craig Etcheson said: ‘We always have a choice.’ And Roux (defense co-lawyer) was exasperated. I think I was, too. It’s so easy to say, isn’t it? If you keep in mind – if one can ever really imagine it – the level of terror in which people had to make choices after 1975, I would refrain from judging what element of free will there would be for the vast majority of us. Free will meant death in this case.

“There was, of course, an element of free will for Duch up to a point; up until he takes responsibility for M-13. After that it gets more confusing. The whole system of thought, the ideology, the training is meant to kill free will. I guess one can say there always is an element of it that remains, but in the specific context of Democratic Kampuchea between 1975 and 1979, it is very hard to know how that surviving element would come out in each of us, or be silenced by much greater forces.”

Did the trial and other research provide any answers about why the revolution literally ‘ate its own children’? “You’re right to call it a vexing question. One thing we may observe, though, is that many revolutions have done so, including the Bolshevik and, most importantly, the original model of revolution for the Khmer Rouge: the French one. Again, the Khmer Rouge hasn’t invented something really new, but seems to have brought it to an even more radical level.

“Does this radicality, disconcerting and overwhelming as it may be, give this revolution a different nature? I don’t think so. I think the elimination, to borrow Rithy Panh’s word (the title of a 2013 book based on Panh’s interviews with Duch), is part of the revolutionary temptation and can be its ultimate result when it reduces the world to a fight between two forces, one representing mankind and the other the enemies of mankind. And when it has to justify its own dramatic failures and lies through the existence of the enemy from within, the elimination has no end. But that’s how far I can go in dealing with the ‘Why’.”

One of the more unsettling accounts in Master is the testimony of Mam Nai, a former interrogator at S-21. In his statements, he emerges as an ‘unreconstructed communist’ who you feel, given the chance, would do it all again. “I believe that there were good people at S-21 and that wrongdoing took place there, but from what I saw there were fewer good people than bad. I have regrets for that small group of good people… I have never regretted the deaths of bad people.”

What of Cruvellier’s own impressions of Mam Nai; was he really as unforgiving as he appears in Master? “Mam Nai’s appearance in court was certainly one of the most memorable moments in the trial. There was an exhibition at the Bophana Centre where Cambodians had been asked to write their memories of the trial. It was striking how many of them referred to Mam Nai’s testimony. Yes, Mam Nai appeared as the unreformed die-hard Communist, an intellectual who had worked so much at becoming the perfect party member that he never would question his revolutionary beliefs and the crimes committed in the name of them until he dies.

“He was the glacial living reminder of the intransigence of Khmer Rouge cadres, especially the educated ones. He was also a disturbing illustration of the selectivity of international justice: Mam Nai, one of the chief interrogators at M-13 and S-21, unrepentant and lying despite all the concrete evidence against him, would leave the courtroom free and undisturbed. And yet his appearance at trial would also prove to be the only moment in his life when he came as close as it gets to an expression of remorse.”

The question of ‘justice’ seems central to what we could desire from Duch’s trial. Did Duch’s eventual sentence represent justice? “If we focus on Duch’s trial, yes, of course, there was a measure of justice: he has been tried, rather fairly; the trial judgment reflected in many ways what was said and learned in court, as opposed to the appeals judgment, which seems to erase all the nuances of the case; he was punished for crimes he had clearly committed. That’s the basic measure of justice a criminal court can achieve.

“The sentencing is a tricky matter. There is no just sentence when it comes to mass crimes. It’s an impossibility, so depending on whose point of view and interests you consider, you are going to strike a balance between irreconcilable factors. In absolute terms, a life sentence seems to be the only one available for 14,000 deaths or more, but sentencing has never worked in absolute terms before other war crimes tribunals: it’s a balance between a number of factors, including the expression of guilt and remorse, the cooperation with the judicial system, etc. That’s why many genocide convicts got lesser sentences before the Rwanda Tribunal, for instance. In that sense, the Trial Chamber in the Duch trial had reached a much more consistent sentence than the absolute one the Appeals Chamber gave. But that has probably hardly anything to do with ‘justice’, certainly not with how it is felt and understood by most victims and civil parties.”

What was the author’s impression of Duch at the beginning of the trial and how did it compare at the end? “My impression – and it’s only an impression, only he knows – is that he came to realise during the trial, and more precisely after the week during which civil parties came and testified and refused him the forgiveness he had naively hoped for, that he wouldn’t get much of what he had wished from the process. As I describe it in the book, there is a striking change in his physical behaviour by the end of the trial. And there is his endorsing Kar Savuth’s absurd and self-damaging move (the defence co-lawyer presented an argument near the end of the trial that Duch should be acquitted).

“To some extent you could say that something broke in him. I don’t think he was broken, but he clearly withdrew. He was silently upset, somehow. I think it’s because he realised that he wouldn’t get what he had hoped for – a measure of redemption, or something along these lines – or what he had been perhaps made to hope for by others. One also has to keep in mind, always, the exhaustion that comes with a trial for anyone who’s in it and for the accused more than anyone else. That’s a factor that is very often ignored, but it’s real. Beyond his exceptional physical and mental strength, Duch could only be exhausted at that point and that also had changed him.”

In Master, Cruvellier mentions more than once the fact that Duch failed, for whatever reason, to destroy the enormous number of files accumulated at S-21. How differently would we judge the Khmer Rouge today if those files, including the thousands of photographs, had been destroyed?

“I believe some of the most respected historians, including David Chandler, agreed that our knowledge of the Khmer Rouge system would be significantly, or even dramatically, less if it wasn’t for S-21 archives. I do not think that the way we judge the regime would be much different, but our knowledge of the system as well as the capacity to bring some of them to court – first of all, Duch – would be very different.”

And what of the progress of the trials under Case 002? “I haven’t followed in detail the proceedings in the second trial, so I can’t comment on their inner value and quality. One obvious observation, though, is that the process has heavily deteriorated after the completion of the Duch case. All international tribunals deteriorate with time; that’s a sad reality. But the time taken to run a first mini-trial in Case 002 that hardly looks into the most serious crimes committed is a disgrace, and the cost related to maintaining all organs of the tribunals working over the past four years on that single case and on the hypocritical handling of cases 003 and 004 has clearly brought to question the integrity of the process.”

Turning the final page of Master, I’m left with one beguiling reflection: perhaps, in the end, Duch represents the Khmer Rouge’s ultimate ‘victim’? A man who believed in its original ideals and was then obligated through personality, fear and his own foibles to continue serving its ‘revolution’, even as it turned in on itself and devoured the people it had vowed to set free. As Cruvellier eloquently writes: “Sometimes broken dreams are like revolutions: they turn into nightmares.”

Master of Confessions: The Making Of A Khmer Rouger Torturer, by Thierry Cruvellier, is available from Monument Books now for $25.