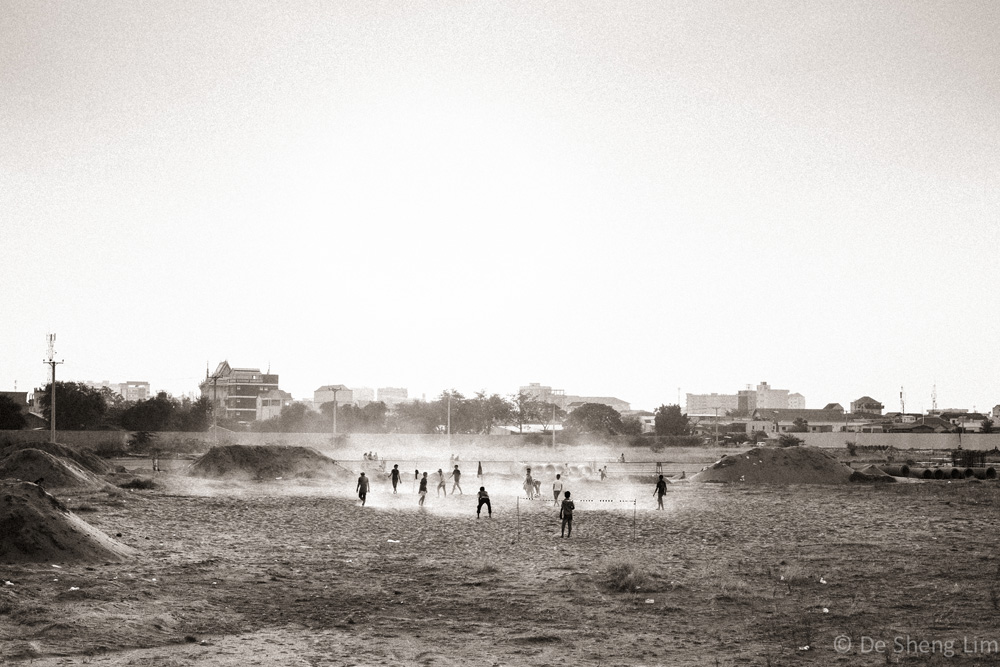

Wandering through the art-filled streets of the Boeung Kak precinct, it’s hard to ignore the immense, artificial sand plain lumped dissonantly in the backdrop. Awkward-looking, but ominous in its meaning, the barren stretch of land is a result of the 99-year lease that was signed to private development company Shukaku Inc. in 2007. The lake proceeded to be filled with sand in the following year, resulting in heavy flooding of the area and the eviction of thousands of locals from their homes. Yet, in the shadow of a recently erected skyscraper in a nearby neighbourhood, children “lucky” enough to remain in their hometown today play happily in the giant sandpit, while older siblings motocross in the dunes.

Four photographers capture the incongruous landscape and the impact of development on the Boeung Kak community and its social dynamics in a new photographic exhibition at Bophana Centre. Three Lives of Boeung Kak illustrates three key aspects of the area’s ongoing transmutation, as seen through the lenses of photographers Julie Bardeche, Vincent de Wilde, Elinor Fry and De Shreng Lim.

An incongruous landscape

Community efforts have proven somewhat efficacious in regenerating the neighbourhood after severe water damage. Organised cleanups and an injection of art and regular music events continue to draw visitors back to the once lively backpacker area. However, the precinct hasn’t entirely shaken the ghetto vibe it adopted since the filling of the lake and mass exodus of the community, with many locals still clearly living an impoverished existence in its wake.

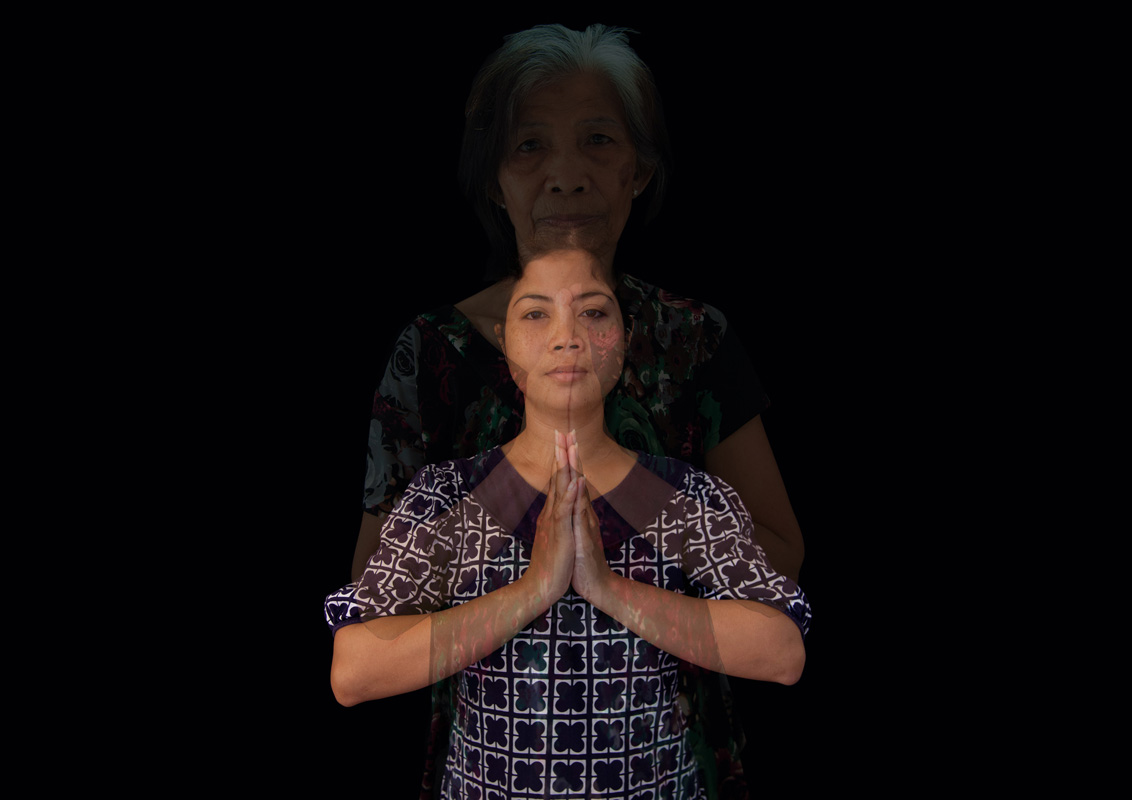

French-born Bardeche explains, “The ‘three lives’ title represents the three angles through which the four of us look at the lake. It’s also evocative of the past, present and future times – I wanted to create a linkage between visual and time dimensions. Vincent’s photos mostly feature life along the railway, to the Southwest of Boeung Kak: a past or soon-to-disappear aspect of that part of town. De’s focus is mainly on the present life on the lake and the sand dunes.”

Bardeche and Fry’s third angle initially intended to focus purely on the street art that has emerged in Boeung Kak in the last few years. As they spent more time in the area, however, she found herself becoming immersed in the lives that lay beyond the graffiti-sprayed facades.

“My photos were first focused on the interactions between the street art and the inhabitants. Nevertheless, as I walked around the lake, I became increasingly interested in life in the sand dunes,” Bardeche says. “In particular, I was struck by the contrasts between the simplicity of the residents’ lifestyle and the growth of high-rise buildings in the background, which foreshadow the future of the area.”

Consequently, the photographers all highlight the stark contrast between the life of the lake residents and the rapid development of the nearby town to some degree within their work. Many of Bardeche’s photos centre around children who play in the sand with smiling faces and torn clothes – cranes and skyscrapers all the while encroaching on the horizon.

Lim encapsulates this incongruity further as he describes his interactions with the young men featured in his Boys of Boeung Kak series.

“I asked them about what it was like living there, and what it was like before the lake was filled. Many were unable to answer. Perhaps they had forgotten what it was like living next to the lake. Perhaps they had become used to the barren landscape that was now their playground,” Lim says. “But some were able to conjure up thoughts and memories of better times. One boy, Panet, age 16, said to me, rather despondently, ‘I don’t have money, because of empty water.’”

And yet, 20-year-old Yong Savon answered, pointing toward the cranes in the distance, that he wanted to be an engineer. “I thought it was poignant that [he] aspired to be that generation that would build Cambodia,” Lim says.

Poignant, perhaps. Though, if anything, the response seems unexpected – if not completely disparate – to that which you’d expect from an individual whose livelihood has been severely threatened by the implementation of such development practices.

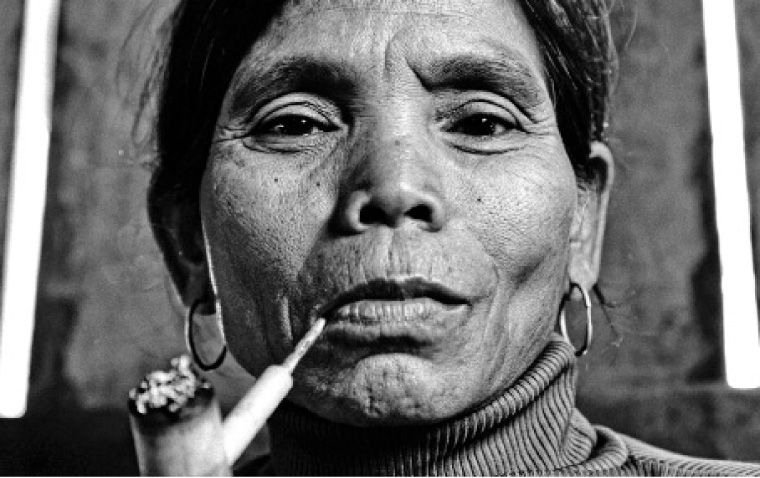

Bernache, meanwhile, spent her time predominantly among the older residents who were relocated within the area. Most are parents of the children who now play in the very foundations of their family’s enduring despair. Old enough to remember the gritty details of the relocation process, the outlook of these individuals is justifiably more harrowed than that of their kin.

“They lost their business and struggle to earn a living,” Bernache says. “They feel injustice, sadness and worry about their future and that of their children and grandchildren. “I believe that they mostly have not been able to adapt to their new situation yet. Some initiatives seek to provide the residents with alternatives – education, housing, legal counselling, jobs and ideas. But it is a slow process and it’s also dependent on how the constructions will evolve.”

United by art

Bernache’s time spent shooting the activity and interactions of the sand dune kids and their parents has paradoxically allowed her greater insight into the significant role played by her initial subject of interest.

“Street art has become an increasingly important part of the life around the lake, as benevolent artists seek to revive the area and attract attention to the neighbourhood,” she says. “This raises funds for local NGOs, which in turn seeks to secure the future of the lakeside area.”

While Bernache does not speak for all locals in the area, many have demonstrated their appreciation of the economic injection and increased traffic afforded by ongoing creative activities. Bernache adds that increased involvement of local artists could add further value to the initiatives.

“I believe in this initiative, especially since it has involved quite a few Khmer artists already. It has certainly attracted positive attention to the lakeside area and the issues faced by its residents,” she says. “Quite a few people did not know about it until they came to an urban art event there. I just hope that more Khmer people will get involved, as the crowd is mostly international. This is, I suppose, just a matter of time and capacity building.”

Simone Art Bistrot is an exemplary model reflecting the growing efforts to regenerate the area through tasteful street art and inclusive music and art events. French owners Ludi Labille and Marj Arnaud were key players in the clean-up efforts following the initial major floods, while their bistro-gallery has earned its crust as a creative mecca both within the neighbourhood and beyond.

Both Lubille and Arnaud have already noticed a rise in local artists who are involved in the beautification of the walls surrounding Simone Art, as well as increased participation in their events. The recent Art in Solidarity festival, designed to unite the community through positive and creative action, saw a mix of local and international artists bearing spray cans and sharing original ideas.

“Solidarity is necessary for us to evolve as a community,” Labille says. “We are collaborating with many different artists and supporters who share this vision and we have plans for future collaborations that will help develop the community and encourage art. It’s about developing art and being human. If we come together we can do great things.”

Three Lives photographer de Wilde echoes the significance of solidarity in his photographs of life by the railway.

“With my photographs, I want to show those glimpses of life and positivity beyond the appalling poorness of this community and the changes occasioned by the filling of the lake nearby,” he says. “Against all odds, for those who remained along the railway, there is somehow a quality of life there, likely due to solidarity, unity and intense social life, like in some Cambodian rural areas.”

De Wilde’s photos focus on maintaining compassion, hope and optimism in times of intense turmoil.

“If viewers look at the community living along the railway with more humanism, empathy and positiveness, I would be happy,” he says. “My photos aim at being both aesthetic and positive. I dislike ‘miserabilism’ and prefer reflecting reasons of hope even in the most sordid conditions.”

While Bernache shares this view, she makes it clear that this should not detract from the grave reality reflected through her series.

“I hope that [viewers] will get a feel of the uncertainties surrounding the future of this area, highlighted by the flaky and ephemeral happiness of the activities and art depicted in the photos,” she says.

Three Lives of Boeung Kak opens 6:30pm, Friday June 19 at Bophana Centre, #64 St. 200.

Those even vaguely tuned into the national art scene will be familiar with the work of Mak Remissa, the locally born artist considered by many to be one of the most successful photographers of his generation. It wasn’t long after graduating from Phnom Penh’s Fine Arts School in 1995 that his talent caught the attention of worldwide publications, many at which he has since worked as a photojournalist. At the same time, his fine art photography began exhibiting across Cambodia, Singapore, China, France, Canada, the US, and beyond, recognised for not only its attention to fine detail, but regular themes concerning the environment and conservation. In his latest exhibition, Water is Life, Remissa emphasises the importance of water for animals, vegetation, humans and life on earth.

Those even vaguely tuned into the national art scene will be familiar with the work of Mak Remissa, the locally born artist considered by many to be one of the most successful photographers of his generation. It wasn’t long after graduating from Phnom Penh’s Fine Arts School in 1995 that his talent caught the attention of worldwide publications, many at which he has since worked as a photojournalist. At the same time, his fine art photography began exhibiting across Cambodia, Singapore, China, France, Canada, the US, and beyond, recognised for not only its attention to fine detail, but regular themes concerning the environment and conservation. In his latest exhibition, Water is Life, Remissa emphasises the importance of water for animals, vegetation, humans and life on earth.