Once upon a time, or somewhere in the vicinity of 10,000 years ago, Neolithic man hit upon a rather novel idea. ‘No more this nomadic life, ’mused our big-browed ancestor, noting the calluses erupting sorely from the soles of his naked feet. ‘Time to dig in and settle down.’ So it was that this one-time wanderer finally sat, twiddled two sticks together in idle distraction, and promptly discovered fire (sort of). What followed shortly thereafter –the hardening of clay pots by heating them in a simple oven, or ‘kiln’ – is known to this day as ‘the first art of fire’.

Ceramics appeared on man’s Can Do list long before the pursuits of metallurgy and glass work. ‘Pinch pots’, made from balls of clay into which fingers or thumbs are inserted to create an opening, may have been the first pottery; ‘coil pots’, formed from long coils of clay blended together, weren’t far behind. Fired at low temperatures, these early pots served both practical purposes and were used to represent fertility gods. Civilisations in Ancient Egypt and the Middle East used pottery in construction in 5,000 BC. As recently as 3,000 years ago, the Chinese were developing the potter’s wheel and various glazing techniques.

By the time the Khmer Empire reached its zenith with the construction of the sprawling Angkor Wat temple complex, ceramics had become a staple of Southeast Asian cultures, nowhere more so than here in Cambodia, where unique techniques and traditions have given the discipline a history all of its own.

Writing in Khmer Ceramics, Dr Dawn Rooney says of the country’s pottery history: “Between the ninth and early thirteenth centuries the brilliance of the Khmers was unsurpassed. Ceramic legacies stimulate our awareness of this ancient civilisation and serve to elucidate life in the Khmer Empire. Ceramics of the period reflect the strength and robustness that were characteristic of an expanding empire. These functional wares tell about the domestic lives of the ordinary people and give an insight into their economy, social structure, culture, and religious practices.

“The appeal of Khmer ceramics lies in their simplicity. Only a few natural materials and basic techniques were used. The affinity of the clay and glaze materials with the earth becomes the strength of these wares. Most Khmer ceramics were stone wares formed from clay with a high iron and sand content. The body is dense, hard, and impervious to liquids. The colours of the clay and glaze are warm and subdued, which is a characteristic of ceramics produced in surrounding cultures during the same period. The decoration on Khmer wares is unaffected and never dominates the shape. It is almost always an incised geometric design rhythmically repeated around the neck, shoulder or body.

“Direct evidence of the shapes of vessels is provided by scenes depicted on stone reliefs at Khmer temples, which offer an insight into the domestic and ritualistic uses of the wares, although the nature of the material is not easily discerned. During the reign of Jayavarman II the ‘temple mountain’ concept, which provided a suitable site to worship him as a god, was introduced. The form of the temple mountain is imitated in Khmer ceramics. Lids are modelled in tiers and culminate in a lotus bud-shaped knob.”

Too often overshadowed by archaeological ‘big game’, Khmer ceramics stand alone in Southeast Asia – and warrant rather more interest than they’ve been granted. Such is the belief of Sam Navarro, the French native and one-time brick-maker who now oversees the running of one of Cambodia’s only traditional potteries. Khmer Ceramics, in Siem Reap, is grooming a new generation of Cambodians fluent in the ceramic traditions of their Khmer ancestors. And for a fistful of dollars, curious foreigners can enrol in a ceramics class, hands gently guided by these native potters, and create their very own one-off piece. Which, as it happens, sounds rather easier than it is.

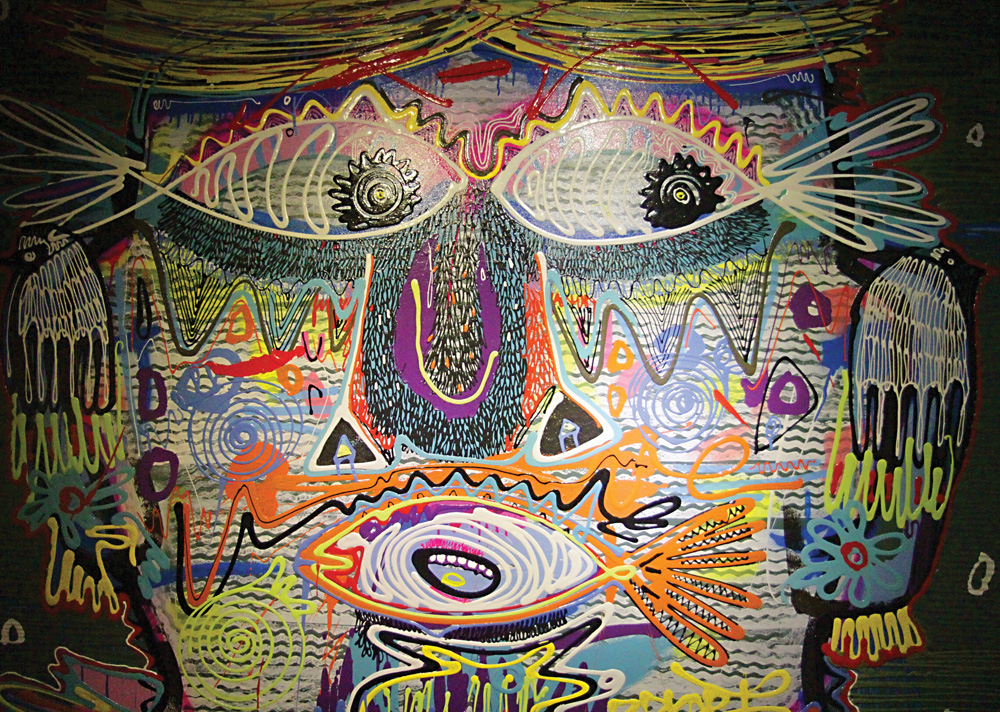

An Olympian god, perched atop a tiny chair, dwarfs the potter’s wheel over which he’s hunched. Calves bulging, he pumps a pedal to keep the flimsy construction spinning as it threatens to fly off its axis and decapitate bystanders. Enormous hands coax a small mound of clay into something resembling a pot, as painted by Picasso. One thumb snags on the still-spinning rim, causing the creation to slowly wilt on one side like a chocolate left in the sun. Its sculptor leans back, beaming, our baffled Cambodian host failing to stifle a well-meaning snigger: “Modern art, baby. It’s totally perfect; you just don’t get it. It’s the new style!”

An Olympian god, perched atop a tiny chair, dwarfs the potter’s wheel over which he’s hunched. Calves bulging, he pumps a pedal to keep the flimsy construction spinning as it threatens to fly off its axis and decapitate bystanders. Enormous hands coax a small mound of clay into something resembling a pot, as painted by Picasso. One thumb snags on the still-spinning rim, causing the creation to slowly wilt on one side like a chocolate left in the sun. Its sculptor leans back, beaming, our baffled Cambodian host failing to stifle a well-meaning snigger: “Modern art, baby. It’s totally perfect; you just don’t get it. It’s the new style!”

There’s a reason the art of fashioning a lump of soggy clay into something that could pass for a ‘creation’ has Biblical overtones to it. Coaxing slimy, reluctant molecules into precise, predetermined shapes aided (hindered?) only by centrifugal forces and the odd basic tool, requires the patience of a deity. Were it not for the forgiving Ghost hands of our young Patrick Swayzes, who mastered the essentials of Khmer pottery in under a month, those wheels would no doubt still be spinning.

As it is, the small Cambodian hand that encloses mine is firm. My fingers, struggling to find purchase on wet clay, are slowly drawn upwards to encourage my nondescript grey lump of wetness to rise up from the wheel. Lump becomes tower. My hand slips. Tower becomes… leaning tower. Two extra hands appear again, nudging the clay back towards the centre of the wheel and out of its Wobble Of Doom. A nudge: both thumbs are to be pressed down in the absolute centre of the spinning mound, opening up a small clay whirlpool that will ultimately form the pot’s lip. Clay snakes coil up from the (very shallow) depths of the whirlpool, spilling out onto wheel, jeans and floor.

The sensation isn’t unpleasant. Cambodian clays vary in colour and texture according to factors such as iron content, natural impurities and firing temperatures, but in their raw form they encourage a very physical reconnection to something entirely natural (the greatest challenge is remembering to keep the wheel moving and ‘throw’ the piece at the same time: staring at a spinning pot has a hypnotic effect, enhanced by the soothing (if messy) massage of wet clay on skin, and the tutor has to keep yelling ‘Spinning! Spinning!’ to jolt me out of near-catatonia).

After the initial throwing, the now proudly erect pot is ‘trimmed’. Holding a cheese wire just above pot’s highest point, you slide your fingers downwards until the wire catches the clay. As the wheel turns, the wire ‘trims’ the clay’s uneven edge, leaving a perfectly smooth, level lip. Then comes the kbach, or traditional carving, a speciality of the centre. Finally, it’s ‘fired’– twice – in a traditional kiln at temperatures of up to 1,500 degrees centigrade.

As Dr Rooney notes, the allure of ancient Khmer decoration lies in its simplicity: evidence of potter’s tools has yet to be uncovered, most likely because they were made from organic fibres such as bamboo, palm leaves, coconut husks and rice straw.

“Coil construction was the method used for medium and large Khmer wares. Evidence is visible in the great number of asymmetrical shapes, uneven lips, and irregular ridges, which can be felt on the interior. Coils were gradually built up from a thick circular flat disc and luted together to form the walls of the desired shape. The Khmer potters also used a turning device, as attested to by the thumb-print scars on the bases of the small wares which were a prolific output in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries. By the twelfth century the ridges on the interior were fairly even, which may indicate the use of a wheel.

“Hand-modelling, the most basic and oldest method of manipulating clay, was skilfully used by the Khmer potters to produce a limited number of shapes in the round. The Khmers were familiar with sculpting and produced superb examples in wood and stone. The potters worked closely with natural materials and retained the texture of the clay. Typical examples of modelled forms are animals, such as the elephant and rabbit, and conches, which are excellent imitations of the metal forms.

“Decoration on glazed Khmer ceramics was used sparingly and never dominated the form. Incising and modelling were the primary methods used throughout the period of glazed ceramics. Simple incised geometric designs with a hesitant quality, continuous horizontal lines, carved ridges around the mouth, neck, or shoulder, and modelled knobs were the earliest forms of decoration, appearing in the late ninth and early tenth centuries. Modelling was used to form applied pieces such as knobs on lids of early covered jars. The method was used extensively in the last half of the eleventh century to form animal-shaped appendages that were applied to vessels.”

“Decoration on glazed Khmer ceramics was used sparingly and never dominated the form. Incising and modelling were the primary methods used throughout the period of glazed ceramics. Simple incised geometric designs with a hesitant quality, continuous horizontal lines, carved ridges around the mouth, neck, or shoulder, and modelled knobs were the earliest forms of decoration, appearing in the late ninth and early tenth centuries. Modelling was used to form applied pieces such as knobs on lids of early covered jars. The method was used extensively in the last half of the eleventh century to form animal-shaped appendages that were applied to vessels.”

Khmer ceramics, the earliest examples of which date back to the seventh century, have long played a prominent role in Cambodian ritual. Then, an eight-day ceremony was held after a marriage had been arranged. The families of the bride and groom remained inside their homes for the duration, with a lamp – often an unglazed ceramic vessel containing oil – burning continuously.

In Champa, after a corpse had been burned on a riverside or beach pyre, the bones and ashes were placed in an urn and thrown into the water. The material was a matter of rank: gold for kings, silver for officials and earthenware for commoners. In modern Cambodia, the dead are still cremated; their ashes placed in an earthenware jar and buried near a temple

Pregnant women are still believed to be vulnerable to evil spirits. By way of protection, a sacred white cord encircles the room where the mother will give birth. Once the baby is born, the placenta is placed in an earthenware jar then buried under whichever tree or plant houses the guardian spirit.

In Champa a corpse was wrapped, carried to the sea-shore or river bank, and burned on a pyre; the bones and ashes were placed in a vessel that was thrown into the water. The material of the vessel depended upon the social rank of the dead person: gold was used for a king, silver for a public official, and earthenware for a commoner.

“Archaeological evidence suggests that ceramics during the Khmer Empir e were mainly reserved for royalty and ceremonies such as weddings,” says Sam, steering us past a traditional kiln radiating heat and into the cool confines of the centre. Shelves are lined with softly lit pieces sculpted into elephant’s heads. Unusual glazes bead on the surface of warm-coloured clays.“In Cambodia, most people used to eat their food on a bamboo leaf; they never really used ceramic plates. It was mostly decoration for kings, monks and ceremonies. Also, the temples at Angkor – especially Bayon – have many ceramic roof tiles.”

The Khmer Empire produced three types of ceramics: green monochromes (the earliest glazed products of Khmer kilns; shards from the late ninth century have been excavated at Roluos, south of Angkor), brown monochromes, and two-colour wares (green and brown on a single piece). “Some of the most sensitive and delicate examples of Khmer craftsmanship,” notes Dr Rooney, “are revealed in two-colour representations of semi-divine beings.” In the late tenth century, a new group of unglazed stone wares appeared. “These wares are classified by Bernard Groslier as Lie de Vin (‘dregs of wine’). The colour of the copper-brown surface of the wares resembles the colour of the residue left in old wine bottles, thus the name.”

As shallow pits with open fires gave way to the first clay kilns, firing became hotter and faster. By the mid-eleventh century, whimsical bird-shaped vessels competed with commanding clay elephants. Soon, rabbits, turtles, horses and mythical creatures appeared. Vastly more ambitious than the simple shapes that had preceded it, this new ‘animal-style’ trend continued to shake up the ceramics scene for the next 150 years.

“The close Khmer relationship with nature is obvious in their ceramic interpretations of realistic and mythical animals, which exude human warmth and earthiness,” writes Rooney.“The Khmers had an instinctive feeling for animals, which evoked naturalism in the ceramic examples. Khmer potters combined familiar subjects and basic materials to produce animal-style wares with a distinct ethnic character, portrayed with spontaneity and vitality.”

As the Olympian scrubs his hands clean of wet clay – or ‘slip’ – at the sink, his Cambodian tutor soothes the still-spinning blob into a shallow plate. The Olympian looks it up and down. “I’ve been teaching you for an hour and you’ve learned nothing?!” he bellows, waving his arms in mock despair. The tutor starts the wheel again. A few seconds later, he steps back to reveal an artfully re-squashed lump of sagging Cambodian clay. “There!” he declares proudly. “It’s the new style!”

WHO: Aspiring potters

WHAT: Traditional Cambodian ceramics classes

WHERE: Khmer Ceramics, #130 Vithey Charles de Gaulle (Temple Road), Siem Reap; 017 843 014

WHEN: 8:30am – 7pm every day

WHY: It’s the first art of fire