Marxist philisopher Henri Lefebvre famously coined the term ‘the right to the city’. Far more than individual liberties to access urban resources, this is a common right to change ourselves through reshaping the processes of urbanisation. Organised by Java Arts, this year’s Our City Festival – founded on the very same precept – brings together a cast of 200, with more than 45 projects and 19 ‘cultural partners’ showcasing the very best of the country’s artistic and architectural talent across Phnom Penh, Battambang and – for the first time – Siem Reap.

…..

Artistic twists on how not fall off your moto; sunset poetry readings on the essence of transience, and an interactive song-and-dance parade featuring cyclos cocooned in coloured string. Dance, sculpture, music, film, literature, painting, photography, performance art: creativity surrounds you, absorbs you, draws you into a world that is familiar yet unfamiliar all at once. Disciplines merge; surprises come in the form of ingenuity, innovation and reinvention. Rotting mansions serve as plinths. Art spills right out of gallery windows and onto the very streets. For almost a month, between January 17 and February 9, the country’s three main urban hubs will come alive with interactive art installations; architectural play spaces; urban flash mobs; spoken word on street corners and myriad hands-on workshops for one and all. The focus: ‘space and its relationship to the individual’.

Jorng Jan (‘Remembering The Past’), an exhibition opening at the Bophana Centre in Phnom Penh on January 25, recreates decades-old stories inspired by family heirlooms to draw attention to how memory and identity play out over multiple generations. Four Cambodian artists – photographers Neak Sophal and Kim Hach, filmmaker Neang Kavich and multidisciplinary artist Kong Vollak – unite in a single space. Here, the artists explore their chosen heirlooms, along with the complex relationships they developed during the creative process with the families each item belongs to.

Creative producer Pip Kelly, from Australia, has been documenting the Jorng Jan project. “It’s all about looking at the good things, the things that people want to remember, document and collect,” she says. “In the future, people who have seen this exhibition will remember their own moments, too. An underlying thread of this project is everyday life: not just focusing on the Khmer Rouge, but before and after; going into the daily lives of what people were doing, like on the weekends or at school or after work or through their relationships.”

On The Streets, hosted here by OCF founder Dana Langlois’ Java Arts Café & Gallery, is a powerful performance uniting six artists from around the world: Cambodian-American Amy Lee Sanford, Ashley Billingsley and Margaret Honda from the US, Kong Vollak (Cambodia), French-Viennese Rainer Prohaska and Saigon-based Sandrine Llouquet. Curator Chương‐Đài Võ has identified street vendor culture on an international level as a powerful topic capable of describing themes of migration, displacement and determination.

“Throughout Southeast Asia, as countries enter and associate with organisations like the World Bank and IMF, influence leads to government decisions that promote gentrification,” he says. “Vendors are seen as people who occupy valuable real estate. A lot of the street vendors are no longer allowed to operate in their downtown areas. Just as street vendors need to be very resourceful, I wanted to reflect that resourcefulness through collaborative action: pair artists up who have never worked together and pair those who have never worked before in a place or know a local culture with those who have: the non-Southeast Asian artists will be paired with Southeast Asian artists.”

Each artist has the opportunity to collaborate, but must also create an individual project based on their respective home culture. In the case of Amy Lee Sanford, Phnom Penh has been home since 2009. Her piece, purely a work of sound, reflects the life of street vendors and at markets throughout the city. “I chose to record things that I hear a lot and also things that people hear a lot but don’t really notice,” she says. “There are a lot of different sounds here… I’m trying to call attention to everyday sounds people don’t necessarily register but they hear.”

Amy’s work focuses on the transfer of ideas and experiences from one person to another. “Sharing work in a different way will be interesting for people here,” she says. “The piece is bringing attention to what people often miss and the attention of sound and how sound affects our own being. It’s a perspective I’m offering, like my pieces in general. There are thoughts and reflections.”

One of the most out-of-the-way elements of the celebrations in the capital must surely be the nightly mini-festival of cinema at Chanthy’s Café at the White Building, featuring film and media works produced by Aziza Film School, Sa Sa Art Projects and the people who call this crumbling landmark ‘home’ (you’ll find Chanthy’s Café on the ground floor, between the third and fourth stairways).

On January 31, attention turns to the festival’s satellite cities: Siem Reap and Battambang. In the former, the human cost of ‘construction displacement’ is explored on canvas by Vincent Broustet and George Whelan; Olivia Bradley’s multimedia performance, Relation, investigates how humans perceive light. Several artists in Siem Reap turned to tourism and the close proximity of Angkor Wat as inspiration. Head West to Battambang, where Mao Soviet is curating, and let local artist Phin Sophorn take you on a ‘tuk-tuk art tour’, or experience the devastating effects of flooding on the city’s crumbling heritage buildings in a performance art installation by Nov Sokunthea.

The overarching vision for the festival, integral to presentation and programming, starts with the curator. This year, that role goes to Sovan Philong, winner of the Samaritaine Young Photographer Prize in Paris last year and originally from Kandal province. For Philong, collaboration is key: “We’re doing the festival for the public, for the people,” he says. “We are all looking at the same ideas, even if they are in different categories. The idea is to support the festival together. We want to tell the people here: ‘If this is your city, we have something we want you to see. We have something we want to show you. It’s kind of a different thing.’ Even if we don’t see 100,000 people, if we only have one person that really wants to see the festival, that’s fine… We would like them to discover what we’re doing, what we want to show and what we have for Cambodian people, including those who are not artists.”

Among this year’s volunteers – a core part of the festival’s sprawling crew – is Hang Sokunthea, who first became involved last year. For her, the festival is an opportunity to breathe new life into an urban culture in danger of falling into neglect. “There are just so many things and places that people have chosen to ignore, to forbid or to allow to be forgotten,” she says. “What I look forward to is empowering people to put love in the city, improve and make the city a better place to live.”

Hor Daro, a 22-year-old architecture student interested in social problems facing urban Cambodia, is one of 28 ‘youth ambassadors’ selected from six universities and trained by Sokunthea to support the festival. “Young people are those who can change our society to be better,” he says of his involvement in the scheme. “Being members of the programme, young people will be inspired to be active and creative to make new things which are very useful to our society.”

WHO: Artists & architects

WHAT: Our City Festival 2014

WHEN: January 17 – February 9

WHERE: Phnom Penh, Battambang and Siem Reap (details at ourcityfestival.org)

WHY: This city is what we make it

…..

FRI 17:

6:30pm @ The Mansion, Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

Ingolv Haaland, a Norwegian composer completing a PhD on music in Southeast Asia, composed the festival’s theme song. Called Siem Reap in honour of his former home, it’s played on the Cambodian tro and Haaland is due to release a new album in April together with Khmer singer Ouch Savy, with whom he performs live tonight. Pandaemonium Dance, meanwhile, is a project spearheaded by choreographer Gillian Rhodes which explores cross-cultural human connections. By contrasting traditional and contemporary dance styles, the performance investigates ‘instability in rapid-fire urbanism and the struggle to maintain identity in modernity’.

SAT 18:

10am @ The Mansion, Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

Cambodia Knits workshop: How To Knit, In Five Minutes Or Less.

3pm @ The Mansion, Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

Tour of the exhibition with curator Sovan Philong and festival artists.

4pm @ The Mansion, Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

Moto Moto, a performance created by Epic Encounters and choreographer Becky Devitt, uses physical theatre to educate on how best not to die in a moto accident.

5:30‐8:30pm @ The White Building rooftop, Street 294 & Sothearos Blvd:

Bonn Phum Nov Bo‐ding (‘Village Festival at the White Building’), a series of cross‐platform goings on put together with the help of The Building’s long-term residents, opens with a sunset performance on the roof of this iconic landmark designed by the doyen of Cambodian architecture, Vann Molyvann. Cloaked in poverty, drugs, sex work and petty crime, The Building in fact houses vast artistic and creative knowledge. Here, this ‘mini-city’ is transformed into a towering, collaborative museum. Look out also for the many pop-up micro-exhibits.

8:30pm @ The Mansion, Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

Cambojam is one of the longest-running international-style music outfits in Cambodia, particularly in their home base of Siem Reap. Eight musicians, carrying Asian passports from Cambodia to Japan and European passports from Russia to the Netherlands, play acoustic/electric/eclectic, covering jazz; folk; pop; reggae; funk, rock and hard rock.

SUN 19:

10am @ The Mansion, Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

Moto Moto, a performance created by Epic Encounters and choreographer Becky Devitt, uses physical theatre to educate on how best not to die in a moto accident.

11am @ The Mansion, Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

Exhibition talk with curator Sovan Philong and festival artists.

2pm @ The Mansion, Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

Cambodia Knits workshop: How To Knit, In Five Minutes Or Less.

4:30pm @ Cambodian Living Arts, #128 Sothearos Blvd

CLA musicians and Tiny Toones dancers set off from CLA’s headquarters to perform a flash mob at The Mansion at 5:30pm, bringing together classical and contemporary music and dance forms, on ‘yarn-stormed’ cyclos covered in coloured string by Cambodia Knits and the Cyclo Association.

5:30pm @ The Mansion, Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

Poetry at sunset, featuring classical and contemporary interpretations of ‘performative poetry’ with both master and emerging poets.

TUE 21:

6pm @Meta House, #37 Sothearos Blvd:

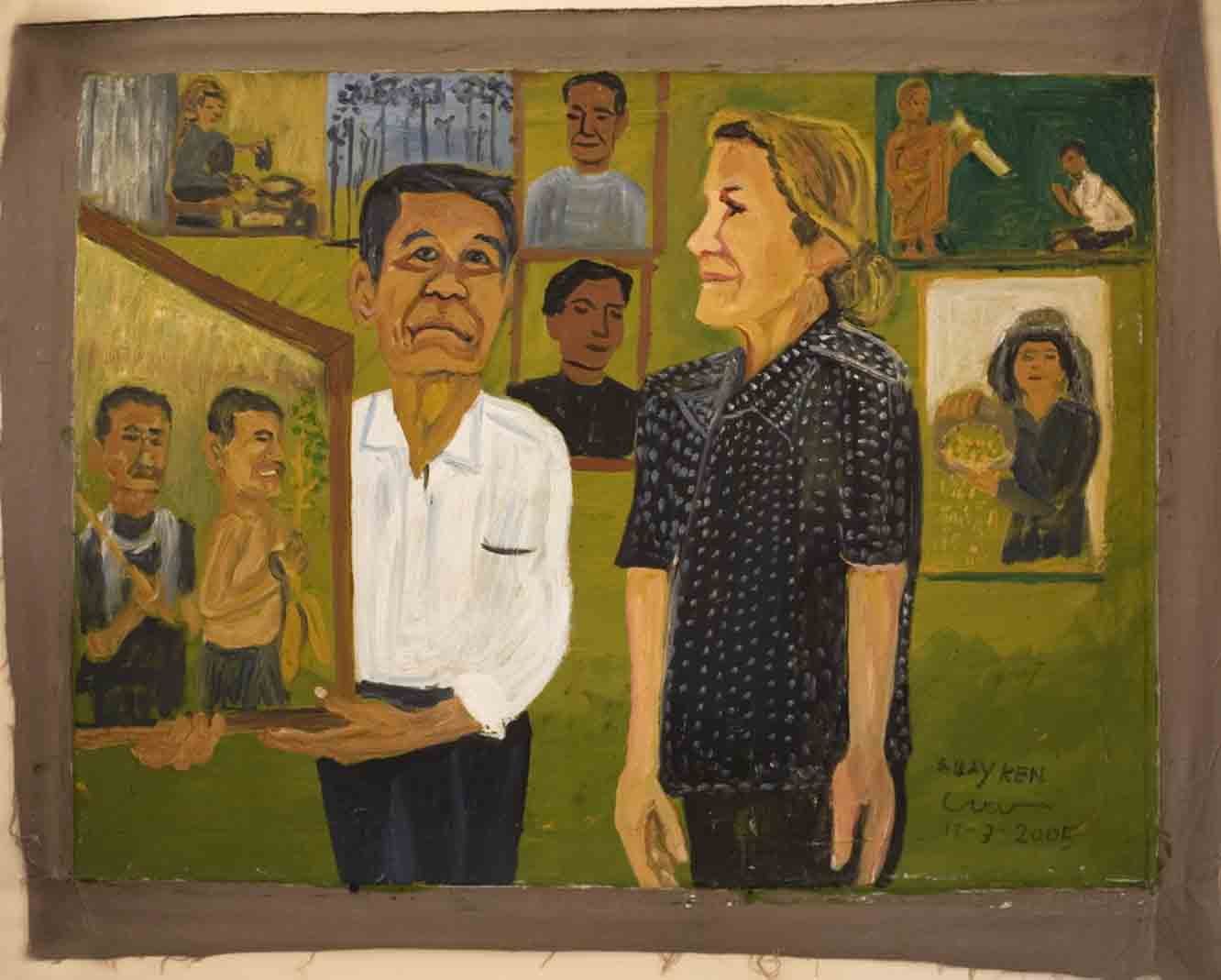

Celebrating one of Cambodia’s late, great masters is the Svay Ken: Phnom Penh Painter exhibition, of which the OCF literature says: ‘From the beginning, Svay Ken set out to record the daily life around him and avoided the grand landscapes of temples and idealised pastoral life that swell Cambodian galleries. The undistorted paintings in this exhibit of friends and family, of survival under the Khmer Rouge, of illness, and of ordinary street life, display the seeming simplicity of style and sophisticated mastery of craft which are the brilliance of Svay Ken’s work. With characteristic humbleness, Svay Ken once said: “My paintings are like a camera of my life of sixty years.” That his work also gives dignity and history to the commonplace lives of the resilient fellow citizens he so much admired is also his genius.’

THU 23:

6:30pm @ Institut français du Cambodge, #218 Street 184:

Body As Site is the result of a workshop by Cambodian-American performance artist Anida Yoeu Ali, with visual arts students from the Royal University of Fine Arts. The five-day intensive asked the question: How can the body be presented as both content and context? Students examined the global history and context of contemporary performance art with a special focus on its emergence in Southeast Asia. FRI 24:

FRI 24:

2pm @ Mith Samlanh, #215 Street 13 (next to Friends restaurant):

In Engineers vs Kids, Advancing Engineering Consultants work with local children to reinvent the city by, among other things, designing and testing small structures made from toothpicks and imagined cities built out of Lego. Join in. And let your kids join in, too.

SAT 25:

8:30am @ Meta House, #37 Sothearos Blvd:

Tour sustainable architecture projects across the city by bus, courtesy of Komitu Architects.

9am @ Sa Sa Art Projects, Street 294 & Sothearos Blvd (second floor, between fourth and fifth stairways):

Artist Nguyen Thi Thanh Mai opens her studio to display art in the making.

3pm @ Bophana Audiovisual Resource Centre, #64 Street 200:

Jorng Jam brings together artists and members of the local community to ‘reclaim, reinvent and remember their family photographs and stories from Cambodia’s vibrant past’. Using film, photography and mixed media, five young Cambodian artists set out to uncover the intimate stories and historical photographs of people living in Phnom Penh during the ‘Golden Era’ of the 1950s and ’60s.

6pm @ Java Café, Sihanouk Blvd:

On The Streets is inspired by Southeast Asia, ‘where sidewalks and plazas are an essential meeting ground for commerce and social interactions’. Six artists examine the effects of globalisation through the prism of ‘vendor cultures’ from Boston, Los Angeles, Phnom Penh, Saigon and Vienna, together producing ‘collaborative actions to respond to the imperatives of mobility and displacement in a Southeast Asian locality’.

8:30pm @ The Mansion, Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

live music from various artists.

SUN 26:

5pm @ corner of Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

Greg Bem, Soknea Nhim and other assorted poets host an outdoor poetry reading and, afterwards, you – yes, YOU – are invited to respond in kind.

7:30pm @ The Mansion, Street 178 & Sothearos Blvd:

Preh Chan Chos (‘Moon Down’) is an improvised performance by the Cambodia-based collective Common Sole, featuring Eric Ellul and ‘combining creative energy from the fields of performance and education’.