The concept of ‘zero’ is perhaps the most paradoxical theory of mankind. At once nothing and everything, it is the basis of the numerical system incorporated into most Westernised societies. Amir D. Aczel investigates its origins in his latest book, Finding Zero.

….

The concept of zero, nought, or 0, is considered to be one of the highest intellectual achievements of mankind, and almost certainly the greatest conceptual leap in the history of mathematics.

The concept of zero, nought, or 0, is considered to be one of the highest intellectual achievements of mankind, and almost certainly the greatest conceptual leap in the history of mathematics.

As science writer and mathematician Amir Aczel puts it, “zero is not only a concept of nothingness, which allows us to do arithmetic well, and to algebraically define negative numbers… zero enables our base-10 number system to work, so that the same 10 numerals can be used over and over again, at different positions in a number.”

Finding Zero describes Aczel’s lifelong quest to discover from whence our number system came.

In the West, the Roman numeral system was used up until around the 13th century, yet didn’t have a zero, and it was incredibly cumbersome. Before that, the Sumerians and Babylonians counted in base 60 (which is still in use today for telling time and measuring angle), but also lacked a zero. The Mayan civilization of Central America used a glyph for a zero in some of their more complicated calendars, but its use varied, and it never made it out of Central America, so it can’t be related to “our” zero.

Aczel’s quest for the first zero takes him around the globe. Along the way, he encounters Indiana Jones-esque artefacts with splendid names, like the Ishango Bone, the Aztec Stone of the Sun, the Bakhshali Manuscript and the Nana Ghat Inscriptions. He travels to Thailand, Laos and Vietnam, and to India, where he studies a stone inscription found at the Chatturbhuja temple in Gwalior, which has been dated to 876 AD, and was long thought to be the planet’s first zero.

Eventually, his research leads him to Cambodia in search of an inscription originally discovered by French scholar George Coedès in 1929. The stone was found among the ruins of a 7th century temple at Sambor-on-Mekong, in present-day Kratie.

The key phrase on the stone is a date marker: “The Chaka era reached 605 in the year of the waning moon,” and can be dated to 683 AD, making it a full two centuries earlier than the Indian zero.

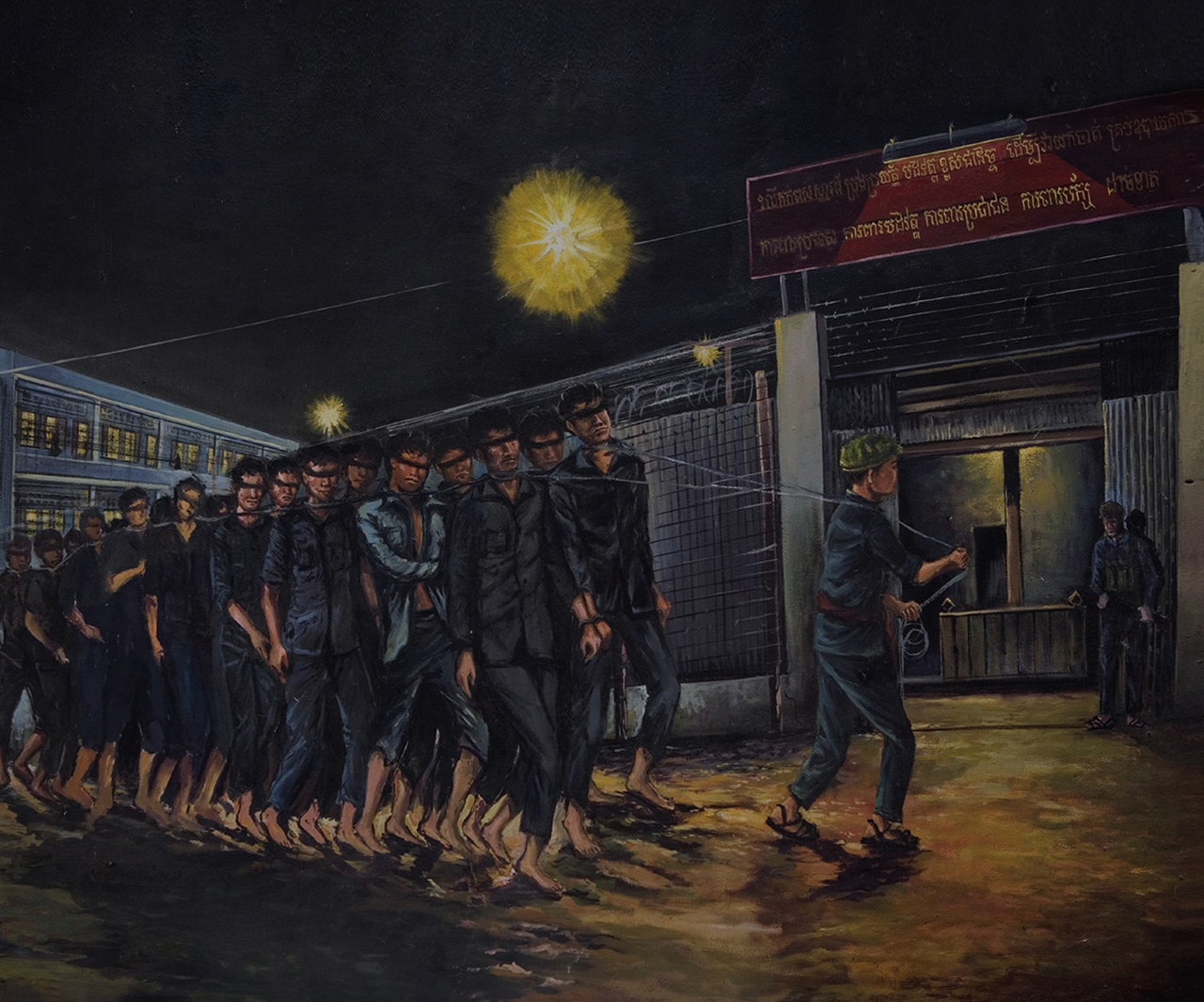

The stone with the zero (actually a dot), known prosaically as K-127, was moved to Phnom Penh, then to Siem Reap in 1969, when it disappeared. Many thought that the Khmer Rouge, with their hatred of culture and learning, had destroyed it. Nevertheless, Aczel tracks it down, rescues it from some entertainingly stupid Italian archaeologists, and sees it consigned, quite properly, to the National Museum (it’s worth noting, however, that K-127 is not on display at the museum, and no one seems to have much of a clue about where it is).

Along the way, Aczel considers whether Buddhist philosophical concepts about being and nothingness could have pushed Eastern thinkers toward developing the concept of zero, and decides that they probably did.

Aczel has written some 20 books on scientific topics. His prolific output and range of interests might make some of his mistakes in Finding Zero forgivable (e.g. Siem Reap does not translate to “Siam Victorious,” and you’d have had to have lived a very sheltered life to describe Phnom Penh’s National Museum as “one of the finest museums in the world”). And while it’s unlikely that “writes like a mathematician” will ever be seen as a huge compliment, Finding Zero is at least clearly and efficiently written, and tells an engaging and important story.

Available at: Monument Books