Sebastien Adnot lives, breathes and oozes reggae. With his lax stance and heavily accented, languid tongue, he could easily have teleported direct from Zion itself. Except that Adnot was, in fact, born in France and is now a proud Phnom Penh expat. Despite being located several thousand miles from the motherland, Adnot is considered by many to be the father of reggae in the Kingdom. Best known as the bassist of Dub Addiction, Adnot is now exploring all new terrain, both personal and musical, with Papa Dub, the recently formed collaboration with percussionist Kacem (KCM) Nayabinghi.

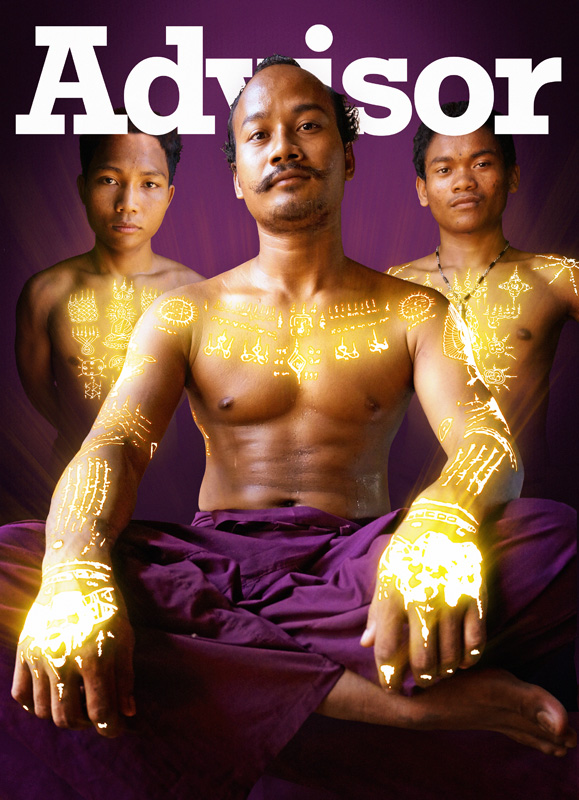

While keeping true to the broader musical genre of the eponymous DA, Papa Dub strips it all back to a more minimalist sound, accompanying live performances with hypnotic visual projections. In this sense, the band could almost be described as the inverse of DA, whose shows are a visual performance within themselves, thanks to their innumerable, animated onstage band members.

“When you go to see Dub Addiction, you expect a show of seven or eight people on stage. We have the mentality of keeping it as massive as possible,” Adnot says. “Papa Dub shows are much more intimate, and reflect my own sensitivity and my vision of Cambodia.”

The camaraderie between bassist/vocalist Adnot and percussionist Nayabinghi is tangible during their live shows. It’s a connection that undoubtedly contributes to the pair’s ability to conjure a room full of harmonious energy and mellow vibes.

“Kacem is one of the few people I call ‘brother.’ We’ve know each other for more than 10 years now, since we met in Marseille. Having a brother next to you is a must,” Adnot says.

A reggae virtuoso to the core, Adnot champions the ideal of peacemaking and good-vibe-spreading. It’s a mentality that pervades all facets of his and his band mates’ lives, from musical composition to personal relations. It therefore comes as little surprise that the conception of Adnot’s solo venture last September was embraced with nothing but warmth and encouragement by the DA crew.

“We always give full support to each other. So, for my first Papa Dub solo concert at Equinox, all the team was there to give strength and positive vibes,” Adnot says. “Papa Dub was actually my nickname in Dub Addiction, and I’m still technically the bass player with the band.”

Since forming DA around four years ago, Adnot has gained enough hindsight to reflect astutely upon his personal and musical growth since the band’s early days. Interestingly, his most immediate observations are perhaps more resonant among longstanding expats than musicians, specifically.

“I formed Dub Addiction in 2011. At this time, I was living in the Kingdom for one year. So the major improvement since then is my greater understanding of Khmer culture, which naturally affects my personal and professional life,” Adnot says. “As a musician, I learned to be more patient. That’s a precious step for all barang here.”

Perhaps contributing to his comprehension of the culture is Adnot’s affinity with the Rastafari movement. When asked to draw fundamental parallels between Rasta and Khmer culture, Adnot doesn’t hesitate to launch emphatically into an exhaustive list. This clearly isn’t the first time he’s thought about it.

“Everything [is similar]! Climate, behaviours, sounds, systems – even the tuk tuks, boats and buses here are green, yellow and red,” Adnot says. “In Rastafarian religion, green represents the homeland and it is a call to action and a reminder that the Earth needs nurturing and protecting. Yellow represents the sun, light and warmth. The light of Rastafari similarly shines on all of us, providing a source of one love, one light for everyone to share. Red symbolises the blood. Red is a cry for equality and fairness that stems from oppression and struggle. Land, love and community. Reggae carries good vibes and values: Khmer people are Reggae, they just don’t know it yet!”

Adnot believes this notion is demonstrable at Papa Dub shows, which continue to attract a sizeable crowd of interested locals.

“Papa Dub is still a more intimate project, but I can see that Khmer audiences react far better than the Barang ones during shows. That’s my biggest reward.”

Having enjoyed touring with DA at various venues and festivals within the Kingdom and beyond, Adnot believes performing locally in both bands involves its own unique set of benefits and challenges.

“Playing in Phnom Penh is comfortable because the audience knows me and I know the venues. Plus, I’m not far from home and my family after the gig .The most challenging part is renewing your music and keeping it fresh, so the people don’t get bored after a couple of shows.” Adnot adds, “Performing everywhere is the same, though, in the sense that we, as musicians, should play for everyone the best we can.”

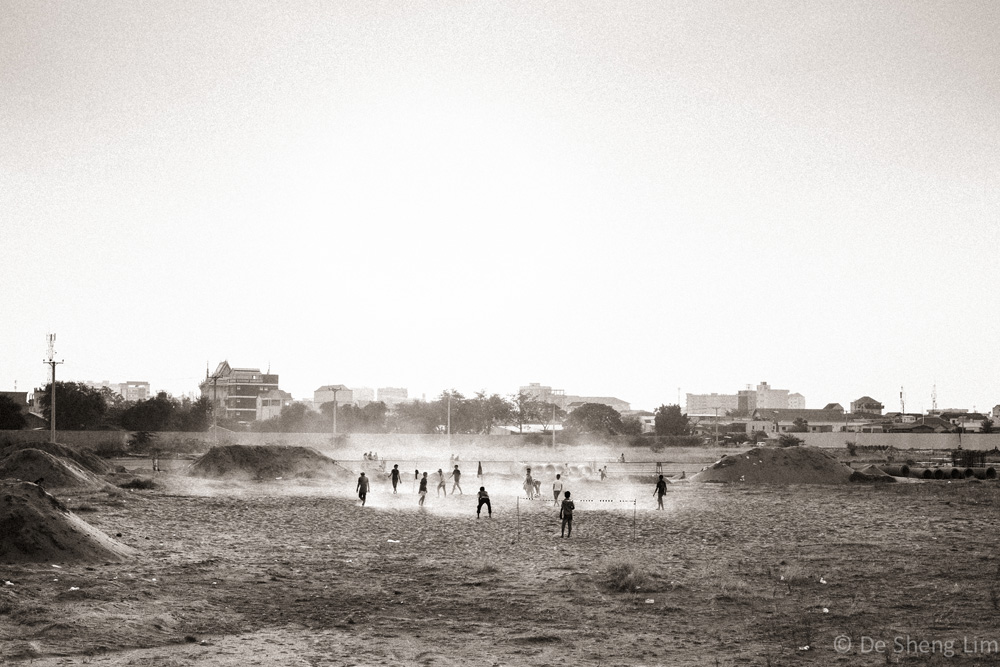

The low maintenance ragamuffin clearly practices this principle. Even with his pick of Southeast Asia’s best venues at his fingertips, Adnot would just as happily play to enthusiastic passersby: “I enjoying playing everywhere, but the street is my favourite,” he says.

After further musing, he adds, with equally modest reasoning, “I would like to perform at the Cambodian Music Festival in Los Angeles. I think it means something to be invited to perform in the US for any musician around the world, and it means something else to be chosen to represent the Kingdom.”

Adnot’s loyalty to his adopted country punctuates his outlook on almost every matter of concern. It’s a mentality that’s understandably accentuated when it comes to Phnom Penh’s music scene. Having watched it grow since he arrived, he remains optimistic that it will continue to do so.

“The music scene [here] exploded since I first arrived, from five to 80 bands. The new Khmer generation of musicians are learning fast and growing in numbers very quickly. Meanwhile, more and more skilled foreigner musicians pass by or settle here,” Adnot says. “Phnom Penh has got a unique potential of creativity because of its own history. It will become the “Pearl of Asia” again, I have no doubt about it. This is the place to be.”

It certainly seems Adnot has found his yard here in the Kingdom. With a strong devotion to a growing musical culture, Papa Dub appears to be in for the long haul. This year, the duo plan to spread their rasta love and smooth vibrations to intimate audiences, delivering stimulating audiovisual live sets and a few new releases.

“I’m currently working on my Papa Dub 2.0 version, expected to be released in September. Until then, I will release a couple of new tunes to give a sip of the new flavour,” Adnot says.

Until then, the duo will continue to gig around town, with their upcoming gig at Sharky’s involving the use of “sound, sight and smell.” The sight and sound is explicable enough. But smell? With no further explanation given, fans will just have to wait until the night to find out whether or not this is just a PC way to introduce newcomers to the whole rasta experience.

Speaking of high (what?), Adnot wraps it up with a sentiment that’ll make you cheese from ear to ear.

“Papa Dub is the dream itself. Taking on a challenging solo project is the biggest high.”

Papa Dub performs at 9pm, Friday June 26 at Sharky Bar, #126 St. 130.