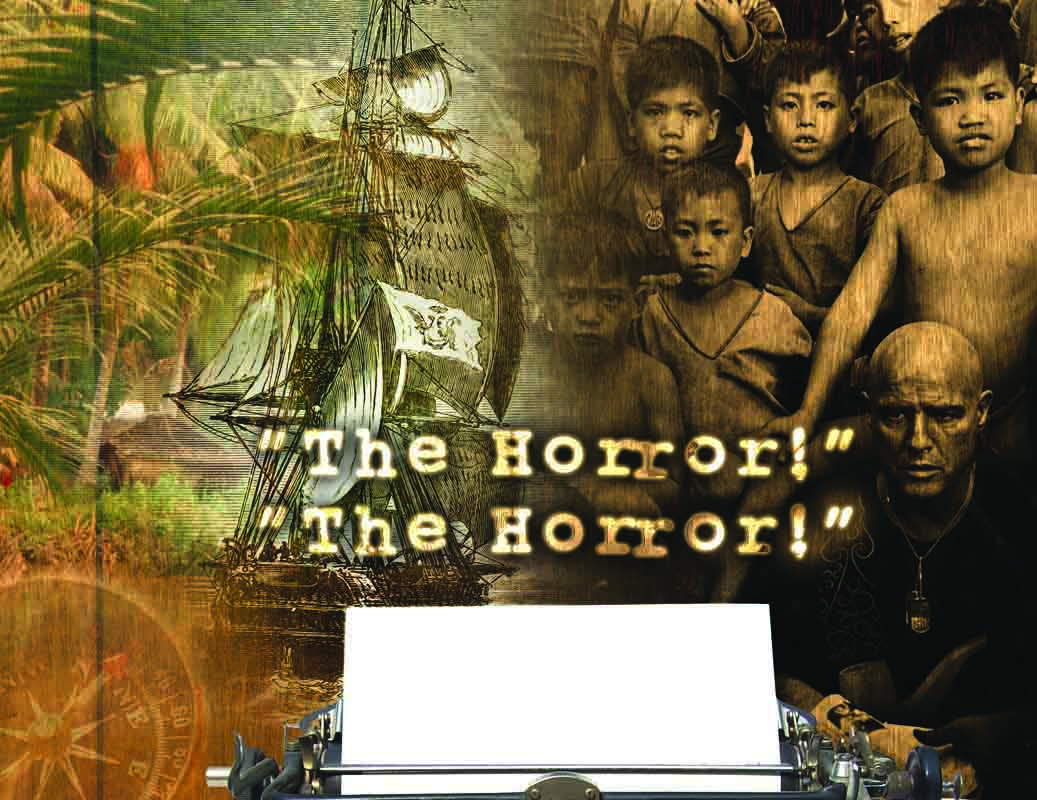

A carved-up photograph of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II with a safety pin through her face has become one of the defining images of punk rock. Created in 1977 by artist Jamie Reid as the cover for the famously banned Sex Pistols’ single God Save the Queen, it cemented the otherwise abstract social ideas the Pistols had sung about a year earlier in Anarchy in the UK. But the roots of punk ideology stretch far beyond the advent of Johnny Rotten; beyond even the sweat-soaked stages of the most venerable punk hang-outs in 1974 New York: clubs like CBGB’s and Max’s Kansas City, where bands such as The Ramones were launching their musical counter-culture manifestos. The seeds of punk’s anarchic politics, far from being American or British, in fact sprouted from mid-20th century French philosophy – philosophy that continues to shape punk to this day. The theory is perhaps most eloquently laid out by Greil Marcus in Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century, in which the author examines punk in the context of everything from Dadaism to Guy Debord. In the prologue, he describes how Johnny Rotten’s first moments in Anarchy in the UK, “a rolling earthquake of a laugh, a buried shout, then hoary words somehow stripped of all claptrap and set down in the city streets…” – I AM AN ANTICHRIST – “remain as powerful as anything I know.” For as Andrew Hussey, head of French and Comparative Studies at the University of London Institute in Paris, once told the BBC: “Punk rock would have happened in the UK without France. But without the French, without their big ideas and their politics and fanaticism, punk rock in the UK would’ve been nothing more than growly old rockers with shorter hair. The real influence of French punk rock lies in the ideas, the style and the ruthless elegance. They never produced a Clash or a Sex Pistols, but what they did was introduce the real politics in punk.” Those politics were the product of Gallic intellectuals hell-bent on cultural subversion and determined to change the world using art and ideas. Led by rebel extraordinaire Debord, they sought disorder versus authority; youthful zeal versus a sclerotic status quo – the very inspiration for what would later be called punk. Debord was a French Marxist theorist, writer, filmmaker and founding member in 1957 of what became known as the Situationist International – a group of rebels whose defining moment came during the Paris riots of May 1968, when they lent philosophical muscle to the students and workers attacking the state. By the time a young Malcolm McLaren arrived at the scene, the streets of Paris were quiet again, but he found and was immediately seduced by Situationist posters bearing slogans such as ‘Be realistic, demand the impossible’ and others that would ultimately find their way into Sex Pistols’ lyrics: ‘Cheap holidays in other people’s misery’; ‘No future.’ Followers of this prankster-turned-philosopher, finally proclaimed a tresor national (‘national treasure’) by the French in 2009, even helped popularise the very technique used by Reid on God Save the Queen: detournement, the process of flipping images directly against themselves and subverting them so that they become ‘cultural weapons’. But the spark that ignited the first flame of punk, ultimately, was one of boredom. Just as the Situationists sought to create a new world order in which urban areas were divided into zones corresponding to specific emotions, a city where you could find yourself in an unexpected ‘situation’ on any street at any moment, so, decades later, punks yearned for radical social change. As Eric Debrais from punk band Metal Urbain, formed in Paris in 1975, remembers: “Everything was black and white: the TV was in black and white, the streets were in black and white. Everyday life was extremely boring; you felt people needed a push so they’d feel alive. The idea was to stir the pot and see what happened and of course people in England were doing the same.” All of this is not entirely lost on Didier Wampas, for the past 30 years lead singer with another French punk band, Les Wampas – one of only a handful to survive beyond the 1980s. Born in 1962 and currently en route to Phnom Penh’s Sharky Bar, he may have been too young to appreciate the philosophy behind the Parisian riots of 1968, but he’s no stranger to music as a vehicle for rebellion. Mention Debord and his Situationists and the affirmations come thick and fast in a French accent equally thick and fast. “Aaaaaaaaaaaaah, yeah yeah yeah,” he bellows over an impossibly awful phone connection from Thailand at the start of Les Wampas’ Asian tour. “Why not? But for me, the beginning of punk rock was in 1976 or 1977. The music is the most important thing for me – the first Ramones album. Punk is about doing what you want; you can make punk music even if you don’t really know how to play. In 1977, every week there was a new single or album. I was listening to all the punk bands: The Clash, The Ramones, the Sex Pistols, The Jam – everything. It was great to be 15 in 1977. I was very lucky.” Wampas is rare among his brethren, refusing for three decades – until May last year – to resign from his job as a public transport electrician despite having produced 11 albums and a top 20 hit. The reason, he says, is that if he were to depend on album sales, it would compromise his artistic independence – a message reinforced with a loathing of artists who exist on government grants. “If you say you’re a punk, to want to have money from the government is crazy. You say you’re anti-system, but you want to have money from the government to play punk rock? I don’t care about working; it’s no problem for me. I can do what I want. I don’t care about radio or TV; I was just working and making music and I don’t care about the rest.” He’s not entirely immune to the trappings of international musicianship, however. Of his first solo album, 2011’s Shut Me Up, he says: “No, no, no. You can’t shut me up. Nobody can. The record company asked me if I wanted to make a solo album and I said no, but then they said ‘Do you want to fly to Los Angeles?’ so I said OK. It was in winter and they said ‘Do you want to go to LA for ten days?’ No problem! I didn’t want to make a solo album; I just wanted to go to Los Angeles. I did all the singing in a one-metre-square cupboard in the producer’s kitchen because it was cheaper than in France. Fun!” Despite having a dig at one of his former bass players on the track Never Trust a Guy Who, Having Been a Punk, is Now Playing Electro’, Didier and his Wampas – who call their take on the genre ‘Ye Ye Punk’ – span a myriad sub-genres, from psychobilly to pop-punk ballads. Les Wampas’ first album, Tutti Frutti from 1984, calls forth the joyous cacophony of everyone from Demented Are Go to The Cramps. “Oh, yes! I love this album but I didn’t want to be in a psychobilly band. I love rock ‘n’ roll and want to play everything, not just one genre. We played with The Meteors, with King Kurt, with all these bands. It was very fun on stage. And we played with The Cramps in the 1990s, which was a mad experience. But in real life, they were just disappointing – no fun at all.” Didier’s latest project is one involving his other band, Bikini Machine, now in the process of recording a new album in London. But if the name sounds as though it was inspired by Dr Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine – a 1965 B roller in which mad scientist Vincent Price creates a gang of bikini-clad female robots with which to seduce and rob rich men – the significance is lost on Didier, who seems more interested in the fact the London studio’s equipment all dated from the 1950s. What is not lost on Didier is how his on-stage philosophy differs from that of the Sex Pistols. Where the Pistols were infamous for spitting at and punching fans, Didier is infamous for singing off-key and in a high-pitched squeak, amd he prefers to climb into his fans’ midst and plant as many kisses on cheeks as possible. But just how long can he keep it up, after a punishing 30 years as a punk frontman? “You just try to stop me! I remember when I was 15, I knew I wanted to play in a rock ‘n’ roll band and I don’t want to stop. If you don’t want to stop, you don’t stop. I eat peanut butter sandwiches, like Elvis! Yes, yes, yes. It’s the secret of rock ‘n’ roll…”

WHO: Les Wampas

WHAT: French ‘Ye Ye Punk’

WHERE: Sharky Bar, St. 130

WHEN: 9pm February 22

WHY: French philosophy inspired punk rock. No, really.