A small boy cradles his face in his hands, wide eyes aghast at the graphic horrors unfolding before them. Mouth contorted in agony, he calls to mind The Scream, expressionist painter Edvard Munch’s iconic 19th-century depiction of existential angst. The look etched onto his features a mixture of mortal fear and incomprehension.

This tiny figure, dressed in a red shirt with yellow dots – the only colour in an ocean of otherwise muted greens, browns and greys – is a lone spectre caught between two worlds: the heady ‘Golden Era’ of 1960s Phnom Penh, a time of beehive hairdos, miniskirts and psych rock, and the dark, nightmarish netherworld of the murderous Khmer Rouge regime.

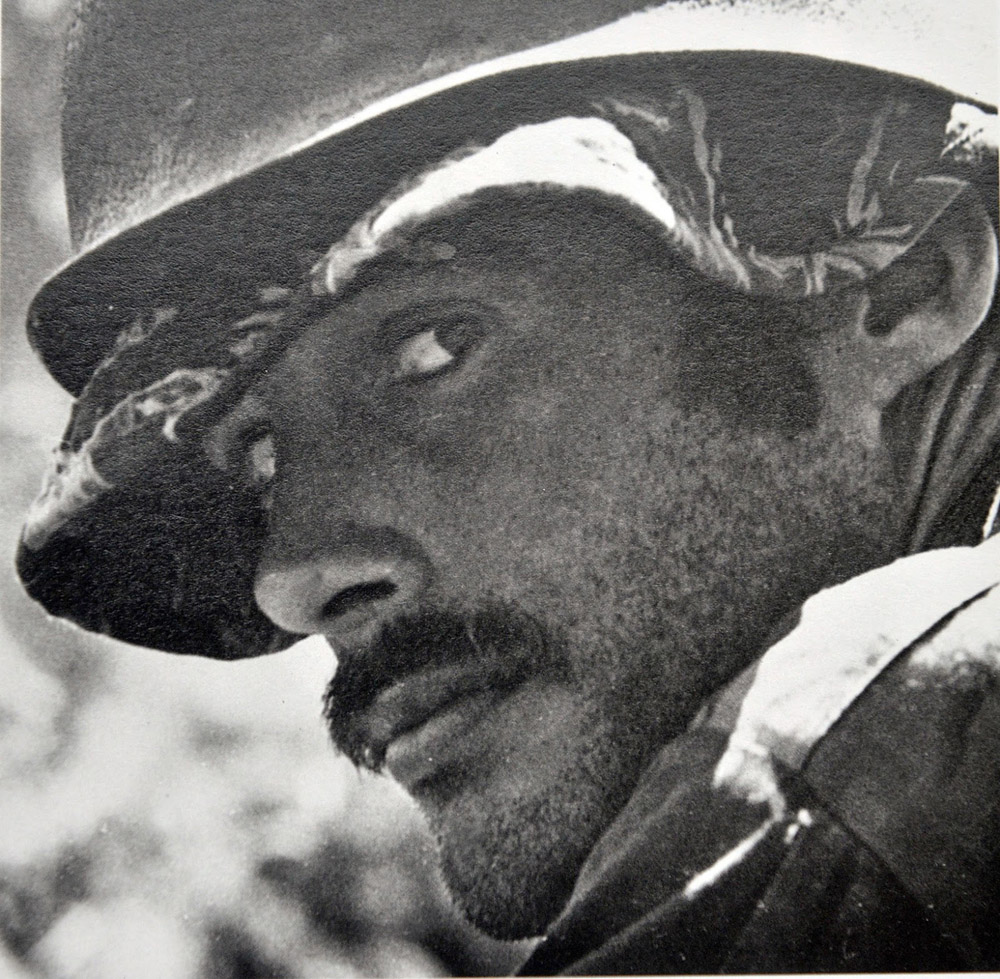

One of hundreds of minuscule clay figurines hand-carved by famed local sculptor Sarith Mang for use in the first Cambodian feature ever to win an award at the Cannes Film Festival, this small, chiselled child is a tiny avatar of Rithy Panh. Today the country’s most celebrated filmmaker, he was 13 when ultra-Maoists seized the capital, frogmarching folk from the city out to rice fields that would later serve as their graves.

Panh’s The Missing Picture, which won the Un Certain Regard prize at this year’s Cannes festival, has been described by hollywoodreporter.com as “a deliberately distanced but often harrowing vision of a living hell”. The image to which the title refers is something that has haunted Panh for decades; photographic evidence to embody the crimes of the Khmer Rouge, or his own endeavours to do so on celluloid.

“For many years, I have been looking for the missing picture: a photograph taken between 1975 and 1979 by the Khmer Rouge when they ruled over Cambodia,” says a disembodied voice as the opening credits roll. “On its own, of course, an image cannot prove mass murder, but it gives us cause for thought, prompts us to meditate, to record history. I searched for it vainly in the archives, in old papers, in the country villages of Cambodia. Today I know: this image must be missing. I was not really looking for it; would it not be obscene and insignificant? So I created it. What I give you today is neither the picture nor the search for a unique image, but the picture of a quest: the quest that cinema allows.”

As the film’s narrator, via a philosophical script credited to Christophe Bataille and voiced matter-of-factly by Randal Douc, Panh’s clay avatar roams through the litany of Khmer Rouge abuses and horrors, positioned in elaborate dollhouse-sized scenes or superimposed using rough-edge visual effects. For 90 minutes these bleak, monochrome scenarios, mixed with grainy black-and-white archive images from the regime’s own propaganda files, are chillingly contrasted with rose-tinted recollections from the filmmaker’s pre-revolutionary childhood.

Asked why he chose to present his quest as a montage of images past and present, Panh says: “It came with the shooting. I bought Chinese acupuncture material and I thought I would start filming with this. Then I interviewed a former Khmer Rouge photographer and cameraman in order to know if there was a missing picture, a picture hidden somewhere. And I ended with clay figurines. In fact, I don’t know why this combination of images. It is like a painter who looks for a special light in his painting; a musician who searches for the blue note, the perfect note. The missing picture is the picture which does not exist and which I was looking for.”

Film spools past on the screen. A young Princess Norodom Devi Buppha, guardian of Cambodia’s Royal Ballet and here swathed in the golden garb of an Apsara, entwines her fingers in physical prayer to the gods. Crowds of 20-somethings twist and stomp to the sound of West Coast rock ‘n’ roll. Pristine cyclos pedal serenely past city markets overflowing with produce.

Panh was born into a world of books, music and laughter, his father a peasant who had risen to become chief undersecretary of education. Theirs was a lively, boisterous family: sisters, a mother. But when Pol Pot set about converting the urban population into pre-industrial ‘noble savages’, there was no place for education. The word ‘study’ took on new meaning. As Panh recounts in his book The Elimination, on which this film is based, Khmer Rouge commanders would tell selected people: ‘The Angkar has chosen you. You’re to be sent away to study. We leave at once.’

The next day, their bodies would be discovered with their skulls smashed in.

In using clay models to depict such atrocities, the speechlessness and immobility of each figurine underscoring the collective helplessness of a people being methodically exterminated, Panh finds a way of representing the unrepresentable – the sort of images that might otherwise be better left unseen. Writes variety.com: “These re-creations are meant to stand in for the unfilmed, unphotographed images that inspired the film’s title: the concrete dikes and rice fields where these former city-dwellers were forced to work; the meagre rice yields they were forced to live on, leading to widespread malnutrition; and the brutal executions that occurred on a matter-of-fact basis. The result is a carefully aestheticised catalogue of atrocities that… generates its own strange, complicated line of ethical inquiry.”

Long live the independent masterful way of Democratic Kampuchea’s Angkar

Long live its extraordinary clairvoyance

Propaganda footage rescued from rusting canisters shows a smiling Pol Pot, or ‘Brother Number One’, waving to the assembled crowds. Black-clad cadres alternately thump their chests then pump their fists in the air, shouting well-rehearsed party slogans. Over each image floats the ever-emotionless voice of the narrator: “Brother Number One was inspired by young humanity. The original people – the Jarai, the Kuoy, the Bunong – a handful of families who shared everything in common. By observing them, he understood. Like Rousseau’s noble savage.”

The clay Panh sits with his head bowed in a muddy field, recounting over mournful strings and clinking cow bells the time a sleepy comrade shared memories of the United States’ Apollo mission – a gesture the storyteller was ultimately made to pay for with his life. “On our moon, there is nothing,” says the thumb-sized sculpture. “Parched earth and dust bury everything. It took me years to learn to walk upon it, bare feet on thorns.” The camera pans to reveal clay water buffalo being herded by a gaunt-looking man wielding a stick. “Muddy water trickles down my throat. Little by little I disappear. I’m nothing any more. It is strange to drink mud. The buffalo watch us. ‘What odd humans to drink our water.’”

Of sculpting the hundreds of cartoon-like figures, a process that took Mang many months to complete, Panh says: “Each facial expression was made according to the requirements of the sequence, and according to my memories, and according to what I had in mind, what I wanted to film. Most important was that the expression had to be a human one. The figurine is the depiction of the soul. It had to be embodied.”

Perhaps one of the most disturbing memories in The Missing Picture is how Panh’s father deliberately chose, with great dignity, to starve himself to death rather than continue living on ‘rations fit for animals’ – a small gesture that nonetheless defied the regime. Yet in suspended animation, despite the crimes to which he was subjected (his sisters and mother also perished), Panh – this eminent chronicler of the horrors of the Khmer Rouge dictatorship – seeks neither judgement nor revenge, only to understand. “My film aims to ensure that the deep wound caused by the Khmer Rouge belongs to the past and that the new generation builds her future with confidence in herself and in her creativity.”

WHO: Filmmaker Rithy Panh

WHAT: The Missing Picture screening

WHERE: Bophana Centre, #64 Street 200

WHEN: 6:30pm August 3 – 10

WHY: The film, rising from the ashes of a system designed to exterminate intellectual and artistic achievement, is itself a powerful form of resistance