“The natural world is our home. It is not necessarily sacred or holy. It is simply where we live. It is therefore in our interest to look after it. This is common sense. But only recently have the size of our population and the power of science and technology grown to the point that they have a direct impact on nature. To put it another way, until now, Mother Earth has been able to tolerate our sloppy house habits. However, the stage has now been reached where she can no longer accept our behaviour in silence. The problems caused by environmental disasters can be seen as her response to our irresponsible behaviour. She is warning us that there are limits even to her tolerance.” – His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, Ancient Wisdom, Modern World: Ethics For The New Millennium

…..

At precisely 14:46 Japan Standard Time on March 11 2011, roughly 70km east of the Oshika Peninsula of Tohoku, Mother Earth finally ran out of patience with us, her human inhabitants. Furiously shaking the floor of the Pacific Ocean in a fit of vexation, she let loose the fifth-largest earthquake in modern history. Towering tsunamis more than 40 metres high tore through the 6,852 islands of the Japanese archipelago, leaving in their sodden wake level 7 meltdowns at three nuclear reactors and nearly 16,000 people dead or dying.

So powerful was the seismic shift triggered by her rage that it bumped the planet an estimated 10cm to 25cm on its axis, moving Honshu – Japan’s main island – a full 2.4 metres east. But that seismic shift extended beyond the purely physical. Aghast at the horrors unfolding before his eyes, one of Japan’s most distinguished choreographers felt his very understanding of humanity begin to topple. Having produced 55 performances in 35 countries over a period of 30 years, Hiroshi Koike – a quiet, thoughtful man who pauses to consider each response before articulating it – promptly dissolved his Pappa Tarahuma dance company. The time had come to contemplate higher things: namely, the pursuit of a better world.

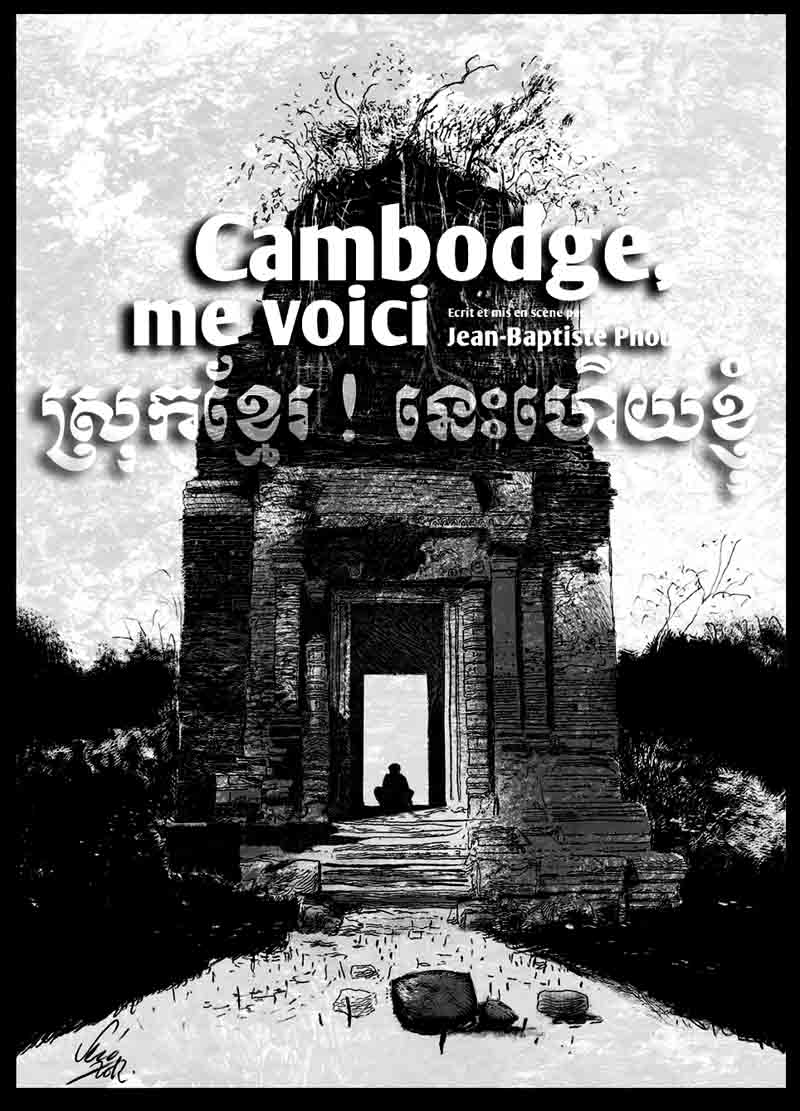

Sitting cross-legged in the lotus position, perched atop a red plastic chair, Hiroshi moves barely a muscle for a full 75 minutes: a hardly noticeable nod here; a fleeting hand gesture there. Before him, on a floor coated in black rubber dance mats, seven performing artists duck, weave, tumble and spin with balletic grace as a large speaker blares out everything from white noise to punk rock and back. Slightly behind him and to the left, a young Khmer musician sits amid a tangle of traditional Cambodian instruments, his haunting melodies occasionally interrupting the recorded cacophony.

Here, in the shadow of a huge circus tent opposite the National Assembly, an Indian epic is being played out. Only this performance is no relic, rather an attempt to build a bridge between ancient Asian wisdom and the idiosyncrasies of the modern world in which we live. The keystone in this existential viaduct almost defies comprehension: an ancient Sanskrit poem made up of almost 100,000 couplets, the Mahabharata (‘Great epic of the Bharata dynasty’) is roughly seven times the length of ancient Greek poet Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey combined and is considered as significant as the complete works of Shakespeare and/or the Bible.

For generations, this particular epic – chiselled onto the walls of Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom, and companion to the Ramayana – served as the foundation for religion, philosophy, politics and law in Asian cultures. Decipher the meaning of this monumental text and you can break free from all evil, legend has it. It’s with such promise in mind that Hiroshi, a former TV director, is repurposing the story for a 21st century audience to pose one rather pivotal question: What does it mean to be human and alive?

“I was so shocked by the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear plant problems,” says the choreographer during a rare quiet moment post-rehearsal. “We have to change our ideas, the structure of our societies, our philosophy. I dissolved my company and tried to make a new bridge project – there are many kinds of bridge I want to build up, for example between ancient times and modern times. We need these bridges between the ancient world, this world and future times. We need to go beyond what has come before, to open our minds. After March 2011, I reconsidered the relationship between humans and nature; traditional culture and modern culture; this world and other worlds. We have to think about what it means to be human. We need to change our philosophy, so we have to talk with ourselves: what is our philosophy? What are humans? What are animals? What is this world? How do all these things work together?”

On the surface, the Mahabharata might seem an unusual vessel for such rigorous self-examination: its mass of mythological and didactic material swirls around a central heroic narrative detailing the battle for sovereignty between warring factions of cousins, the Kauravas (the ‘bad’ side) and the Pandavas (the ‘good’ side). Set sometime before 500BC, this long-winded tale of Hindu war is believed to have been primarily authored by the sage Vyasa (with a little help from his friends, of course).

The story begins when the blindness of Dhritarashtra, the elder of two princes, causes him to be passed over in favour of his brother Pandu as king on their father’s death. But a curse prevents Pandu from fathering children and his wife asks the gods – Dharma, the wind, Indra and the Ashvins – to father children in Pandu’s name.

The bitterness that develops between the cousins as a result forces the Pandavas to leave the kingdom when their father dies. During their exile the five jointly marry Draupadi – born out of a sacrificial fire, who Arjuna wins by shooting an arrow through a row of targets – and meet their cousin Krishna, friend and companion. The Pandavas return to the kingdom but are again exiled to the forest, this time for 12 years, when Yudhishthira loses everything in a game of dice with the eldest of the Kauravas.

The feud culminates in a series of great battles on the field of Kurukshetra (north of Delhi, in Haryana state). The Kauravas are annihilated and, on the victorious side, only the five Pandava brothers and Krishna survive. Krishna dies when a hunter, who mistakes him for a deer, shoots him in his one vulnerable spot – his foot – and the brothers set out for Indra’s heaven. One by one they fall along the way, Yudhishthira alone reaching the gates of heaven. After further tests of his faith, he is finally reunited with his brothers and Draupadi, as well as his enemies, the Kauravas, to bask in perpetual bliss.

But this text is about more than myths and legends: equally, it’s an examination of dharma, or Hindu moral law. These much revered codes of conduct – including the proper conduct of a king, of a warrior, of an individual living in times of calamity and of a person seeking to obtain freedom from rebirth – are exposed as so subtly conflicting that at times the hero cannot help but violate them, no matter what choice he makes.

And therein lies its relevance to all of humanity, a relevance director Peter Brook emphasised by using an international cast in his nine-hour-long 1985 stage play – an overtly ambitious endeavour that raised more than a few thespian eyebrows at the time. Hiroshi’s cast, by contrast, is proudly pan-Asian: four Cambodians, two Japanese, one Malaysian. Between them, the seven performing artists play a plethora of roles – up to five per dancer – an effect achieved on stage through the rather cunning use of lightning-quick costume changes; the ingenious deployment of masks and subtle alterations in movement and mood.

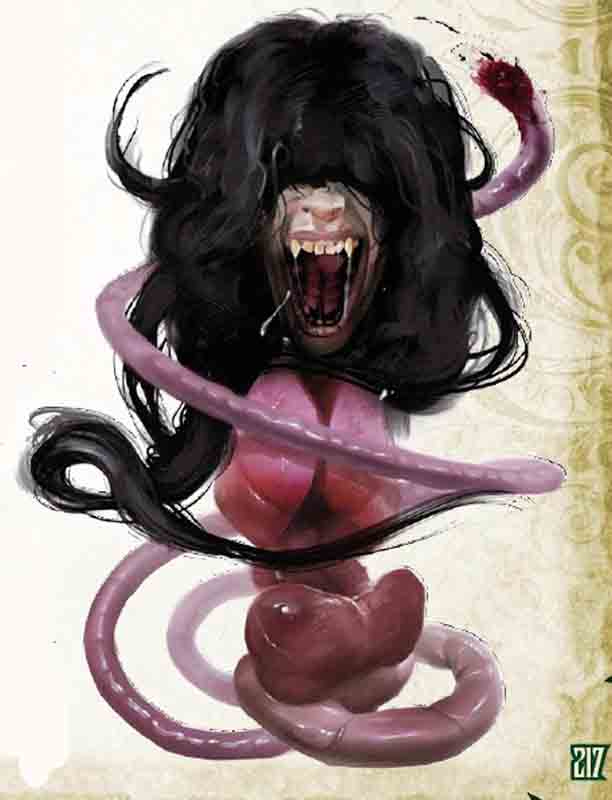

Glistening with sweat in the humid afternoon air, the female lead squats at the edge of one of the mats and offers up a cheery ‘Hello!’ Chumvan Sodhachivy, better known as Belle, plays the parts of Draupadi, Bakasura following, Ganga and Kuru. “We play many roles, so we have to change very quickly: the feeling and also the action,” says this graceful Cambodian dancer. “It’s quite a challenge – and we’ve only been rehearsing for one month and one week. This performance has many layers: many different kinds of things are mixed together. The challenge for me personally is in the last scene, when I have to scream. Koyano Tetsuro taught me the technique because I’m really bad with screaming, but he wanted it. Normally the girl is always sweet and when something happens to her she is quiet and crestfallen, but for this performance he wanted to completely change that: you have to open your heart and scream.”

Koyano, a rubber-faced, Japanese-born specialist in Balinese masked dancing who plays four separate roles in the performance, beams at her side – apparently enjoying having his facial expressions clearly visible for once (“His eyes are so big!” exclaims Hiroshi). “We Asians have wisdom from the old ways about how we can best live with nature,” he says. “In Japan, we value this. Now we have to redefine it and recreate it for this modern world. It’s not only about performing arts. I studied a lot of philosophy as well in Balinese culture. We chose the Mahabharata because it is the greatest story in Asia. The story is a source of art, a source of philosophy, a source of society – everything. For example, in Bali they use this Mahabharata story in the famous shadow puppet shows. Before, they didn’t have any schools in which to educate their children so people would go to shadow puppet shows. In the Mahabharata story, it talks about many important philosophies, wisdom and how people can live together in society and co-exist with nature. This is a form of education as well.”

WHO: Amrita Performing Arts

WHAT: Mahabharata dance performance

WHERE: National Theatre, #173 Sangkat Toul Svay Prey I (behind Spark Club, off Mao Tse Tung Blvd.)

WHEN: 6:30pm July 12 & 13

WHY: We are all custodians of an increasingly beleaguered Mother Earth