Exclusive: chapter one of a lavish new book on the making of this, our kingdom

The first rays of the morning sun play across golden temple roofs. A couple of saffron-robed monks, alms bowls in hand, meander down the riverfront, lined with shop houses and colonial-era villas. Residents patiently wait in front of their homes with food donations for the bonzes, as tradition dictates. A lone open truck, loaded with garment workers on their way to their factory, all of them wrapped up against the sun, rumbles around the Independence Monument, the women’s laughter trailing after the vehicle. Store owners pull up the iron shutters of their shops or give thanks for their first sale of the day by brushing bundles of riel, the country’s currency, across their wares. In front of the Royal Palace, a couple of women have set up shop with pyramids of small wooden cages, filled with tiny birds. Passers-by are invited to release one of the birds, for good luck, and for a modest fee. On the Tonlé Sap River, fishermen steer their long-tail boats through choppy waters, catching their breakfast right in front of the palace. A gang of half-naked children uses the jutting wood planks of a construction site as a jumping board from which to drop, with accompanying woops and screams, into the brown waters below. It’s a fleeting moment of peace and quiet, in which Cambodia’s capital looks like an urban idyll, a fairytale small town from a children’s book. An hour later, the riverfront is crammed with the morning rush-hour. Thousands of motorbikes, separated now and then by taxis, trucks, huge SUVs or gleaming Mercedes, push along Sisowath Quay, the road along the river, at a snail’s pace. Disparity of wealth dictates traffic flow. Pedestrians and stall owners fill the sidewalks; blind street musicians among them, usually led by children, play mournful tunes on the tro che, a Cambodian fiddle, its neck long and thin, its body covered with snakeskin. Women balance trays piled high with lotus pods – the seeds are a popular snack – or fried insects, another traditional fast food, on their heads and patrol the river promenade. An elephant proudly ambles from Wat Phnom, the hill from which the city derives its name, down to the palace and collects fruit from several restaurants en route, trailed by children making a living from selling English-language newspapers to the tourists attracted by the pachyderm.

By midday, the excitement has died down, the market vendors have retreated into their hammocks, strung up in their tiny stalls above their produce and the heat tires even the most ambitious of street dogs. Every now and then a cyclo, a pedal-powered rickshaw, floats by in slow motion, its driver invariably smoking a cigarette, his face hidden under the brim of his hat, in search of a fare or the next patch of shade. In the late afternoon, shops reopen and by early evening, the city centre becomes clogged once more. Now youngsters cruise around on their mopeds, showing off new-found wealth, out to impress members of the opposite sex.

Phnom Penh is an attractive, manageable city, dotted with temples and markets, largely free of high rises, and it comes with a somewhat ramshackle atmosphere that mirrors Cambodia’s turbulent colonial and recent history. Walk the back streets in the late afternoons, around Phsar Thmey, the yellow domed art deco market, its hundreds of stalls selling anything from a side of beef to photocopied Lonely Planet Guides, or drop by the National Museum, a stunning colonial-era terracotta structure, a sight in its own right, and the world’s finest depository of Khmer sculpture, and you might feel like a temporary participant of time travel into a retrofitted Indochinese past. Phnom Penh, lacking many of the benefits and challenges of your average Asian metropolis, has style, a vibe, a sense of quick familiarity that is nine parts illusion and one part make-believe.

In 1967, Lee Kuan Yu, Singapore’s first prime minister, visited Cambodia’s riverside capital. As he sat next to his host, Norodom Sihanouk, then Cambodia’s head of state, in the back of a Mercedes convertible, passing along the capital’s wide tree-lined avenues, Kuan Yu remarked: “One day, my city will look like this.”

Phnom Penh, current population around two million, 90% ethnic Khmer and, like the rest of the kingdom by the Mekong, predominantly Buddhist, has been many things: a trading post in the 15th and 16th centuries, often dominated by Siamese or Vietnamese interests, almost stolen by Spaniards and Portuguese mercenaries and freebooters, the city was taken over by the French in 1865 who affectionately praised it as the ‘Pearl of Asia’. Following independence from France in 1953, King Sihanouk ushered in what many Cambodians today consider as the country’s golden age and brought profound changes to the capital. But this brief era of cultural and architectural bloom came to an abrupt halt in 1975, when the communist Khmer Rouge turned Phnom Penh into a ghost town and Cambodia into a graveyard.

Many Cambodians today would like their capital city to look something like Singapore. But Phnom Penh is still a long way away from realising such ambitions and remains hugely overshadowed by Angkor’s grandeur, the main reason Cambodia’s capital receives less accolades than it deserves. A turbulent history, fascinating local and colonial architecture, a stunning riverside location, a friendly population and a sense of proportion make the Pearl of Asia one of Asia’s most enigmatic, unspoiled and relaxed capital cities in the region.

The legend of Phnom Penh

Phnom Penh’s origins are soaked in myth and legend. It’s said that in the 14th century, a rich widow named Daun Penh discovered several tree trunks that had been washed up on the shores of the Mekong. The trunks contained four Buddha statues and a statue of Hindu deity Vishnu. Daun Penh was so impressed by this apparent miracle that she animated other local people to create a small hill, crowned by a temple built to contain the sacred Buddhas – the fruit of the widow’s labours is today’s Wat Phnom. Phnom means ‘hill’ in Khmer and, combined with the widow’s name, Penh, the name of the capital was established. A separate shrine was built for the Vishnu icon. For centuries, Wat Phnom remained the city’s highest point, until a bank constructed the Cambodian capital’s first skyscraper. Today, it’s still possible to climb the modest elevation, via a wide stairway flanked by sacred naga snakes, right up to the temple – the current building dates back to 1926 – where locals make daily offerings. The widow Penh is thought to have turned into a powerful spirit, to whom a smaller shrine on Wat Phnom is dedicated, as well as a new statue, erected in 2008, which stands between the capital’s only hill and the new, heavily fortified US embassy. A large chedi near the hill-top temple contains the ashes of King Ponhea Yat, who is credited with moving the Cambodian capital from Angkor to Phnom Penh, following the Siamese sacking of the ancient Khmer kingdom in 1422. At the foot of Wat Phnom, souvenir vendors, fortune tellers and gamblers all congregate in the course of the day.

A city is born

Contemporary scholars suggest that the establishment of Phnom Penh was directly related to Angkor’s declining fortunes. The area had probably been inhabited by village communities for some two thousand years. In the 15th century Cambodia, choosing a new capital was all about trade. Phnom Penh, then called Chatomuk, the ‘Place of the Four Faces’, lay right in the heart of the country, on the banks of the Tonlé Sap River, and in spitting distance of the Mekong, one of Asia’s most important streams. Phnom Penh could keep a tab on river traffic from Laos, moving rare gem stones, highly priced bird feathers and other natural products from the Southeast Asian interior south to supply Chinese trading vessels. The city was also close to the nation’s main source of protein, the nutrient-rich waters of the Tonlé Sap Lake in the centre of the country, and had easy access to the flow of Chinese goods that moved up the Mekong from the southern river delta in today’s Vietnam. By the end of the 16th century, Phnom Penh probably numbered between 10,000 and 20,000 inhabitants.

Following the fall of Angkor, Cambodia’s immediate neighbours, Siam and Vietnam, flexed their political, economic and military muscles more frequently and Cambodia became increasingly weakened by continued invasions, courtly intrigue and political infighting. As a consequence of shifting regional allegiances and conflicts, the capital moved from Phnom Penh to several other locations in the area. Spanish and Portuguese adventurers, missionaries and freebooters also played pivotal roles in the city’s emergence during the 15th and 16th centuries, by marrying into local nobility and ingratiating themselves with various royal factions, but Christian missionary efforts were lost on the devoutly Buddhist population and early European influence faded as quickly as it had become established, leaving behind few traces. In 1772, Phnom Penh was sacked by the Siamese, further destabilising the country.

Cambodia’s colonial capital

Only in 1865, during the reign of King Norodom I, as the French established a protectorate in Cambodia, did the city become the nation’s permanent capital. The new colonial masters embarked on an ambitious campaign of urban planning. European engineers and local labour drained swamps, created a city grid of roads and landmarks, constructed canals and built a viable port. The shape of Phnom Penh as we know it today, first outlined during the reign of Ponhea Yat in the 15th century, really came into its own under French administration and had grown to around 25,000 inhabitants by the 1870s.

The heart of this colonial city is dominated by the Royal Palace, built in the 1850s and similar in design to the Grand Palace in Bangkok. The palace remains the residence of Cambodia’s royal family. It was constructed in the location of an older citadel which had been ransacked by the Siamese in 1834. The high walls around Preah Barom Reachea Vaeng Chaktomuk, as the building is known locally, contain a wonderfully maintained tropical garden, dotted with various royal buildings. The Khmer Rouge left the complex intact, though many royal possessions were looted. Today, visitors can enter the 59-metre-high Throne Hall, built in 1915 and adorned with ceiling frescoes depicting scenes of the Reamker, Cambodia’s national epic, a variation on the Ramayana, one of Hinduism’s great poems. The more impressive Silver Pagoda is aptly named after the 5,000 silver tiles which cover its floor and were laid just prior to the Khmer Rouge years. The Silver Pagoda houses a life-size golden Buddha encrusted with more than 9,500 diamonds. Locals know this building as Preah Vihear Preah Keo Morakot, ‘the temple of the Emerald Buddha’, which, dating back to the 17th century, also survived the years of recent turmoil.

The area in front of the palace serves as a meeting ground for the city’s population. In the evenings, the garden in front of Preah Thineang Chan Chhaya, the palace pavilion, is home to snack vendors, mobile stalls selling plastic toys and sweet sellers plying their trade. This is one of the best spots in the city to enjoy Bon Om Tuk, the annual water festival. During this three-day festival, which celebrates the reversal of the Tonlé Sap River’s flow, more than a million Cambodians flock to the capital to watch boat races in the day time and barge processions at night. Nearby, Wat Ounalom, the city’s oldest temple, said to have been built in 1443 but possibly much earlier, is the residence of the head of Cambodia’s Buddhist council, the Sangha. The National Museum, designed by French archaeologist George Groslierand constructed between 1917 and 1920, stands just a little north of the palace.

Directly to the south of the palace, the area formerly known as the Cambodian Quarter once housed court officials and powerful politicians and remains a preferred residential area of the families aligned to Cambodia’s ruling party. Just north of the palace, Sisowath Quay is teeming with bistros, restaurants and hotels, the well-known Foreign Correspondents Club among them. During the French occupation, shop houses on this stretch of riverfront served the many trade ships that came up the Mekong to visit the city. Following the rainy season, when the rivers were swollen, vessels up to 6,000 tons would call, load and unload here. Today, riverside apartments are sought after by the thousands of highly paid international aid workers that make Phnom Penh the world’s donor capital.

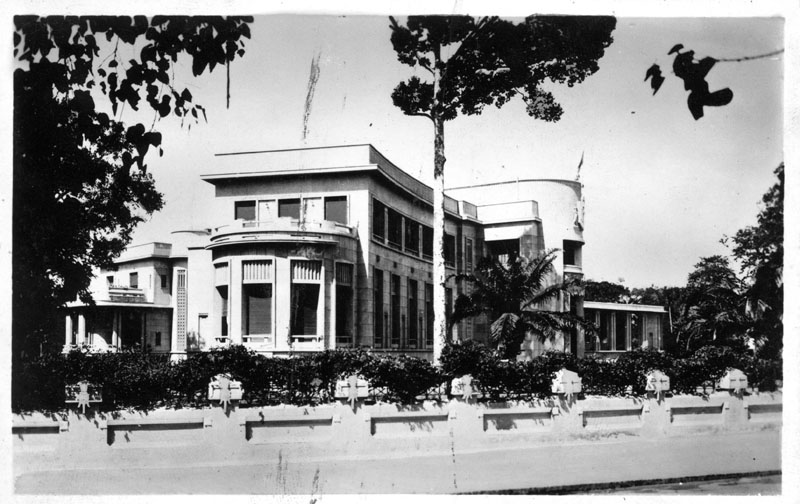

The city’s main thoroughfare, Norodom Boulevard stretches from Wat Phnom all the way to the Independence Monument. Between this traffic artery, lined by ministries, embassies and hotels, and the river, the Chinese Quarter, home to Phnom Penh’s formerly sizable Chinese population who controlled much of the commerce in the city, spread until the 1970s. Further north, around Wat Phnom, the French Quarter, once a picture-perfect pocket of provincial France, formed the heart of the colonial government infrastructure as well as the occupiers’ main residential area. Many of the old villas are gone now, but the post office square, partially restored, gives visitors an idea of what the French effort in L’Indochine once looked like. In recent years, the area has repeatedly served as a film set, for Matt Dillon’s beautifully crafted independent movie City Of Ghosts, as well as for the French production Deux Frères, for which the post office square was temporarily redesigned to its full colonial glory. Besides the post office, the National Library and the National Archives, the luxurious Hôtel le Royal and the former residence building, once home to France’s highest-ranking official in Cambodia and now a ministry, remain. Built between 1934 and 1937 on a former marsh in the area, Phsar Thmey, the Grand Market, is a stunning art deco dome, recently restored to its former egg-yoke colour glory.

Phnom Penh’s golden era

Following independence, Phnom Penh, under the leadership of the enigmatic, capricious and ultimately disastrously vain king, prime minister and head of state Norodom Sihanouk, quickly transformed from a French colonial backwater into a modern capital.

Sihanouk, thought of by the French as a pliable monarch, proved to be a self-confident visionary in the early years of his reign, which continued in one form or another until 1970. Young men whom Sihanouk had sent to France in the 1940s and 1950s to study returned with new ideas and skills. Artists and architects transformed Phnom Penh into a capital so stunning, not even the French could have envisaged it. Among the young king’s urban visionaries, one man truly stood out: Vann Molyvann studied law and architecture in Paris in the 1940s. Having been trained by Le Corbusier, he returned to Phnom Penh in 1955 and was appointed chief national architect. Over the next fifteen years, Molyvann built scores of monuments for an independent Cambodia that fitted well into the older colonial grid of the city. Molyvann designed the city’s first apartment blocks, the Independence Monument, the Olympic Stadium, parts of the university campus on the road to the airport and the Chaktomuk Hall, by the riverside, north of the Royal Palace. His building style, called New Khmer Architecture, corresponded closely to Sihanouk’s vision – to marry Cambodia’s glorious past with modern aesthetics – and remains the only significant architectural school to emerge in post-war Southeast Asia.

Phnom Penh: city of ghosts

Following the coup against Sihanouk in 1970, the golden era quickly unravelled. The economy, long used to American dollars, faltered and Phnom Penh’s building boom ended. In the early 1970s Phnom Penh swelled from half a million to two million inhabitants, with countless refugees trying to escape US bombing and widespread fighting in the provinces. But the Khmer Rouge quickly grew in force and on April 17th 1975, they took Phnom Penh. The city’s darkest chapter was about to unfold.

Within days of the overthrow of the Cambodian government, the stone-age communists forced the city’s entire population into the countryside. Homes, hospitals and schools were emptied and those not strong enough to walk were left to die. Educated urbanites and those with obvious connections to the regime were branded ‘New People’ and many were killed outright. Hundreds of thousands of others were forced to work in huge communes, where many starved. Almost overnight, Phnom Penh turned into a ghost town. A few ministries, factories and foreign embassies remained open and the innocuous Tuol Svay Prey High School was turned into Tuol Sleng prison, also known as S-21, where some 17,000 alleged enemies of Democratic Kampuchea, as the country was now called, were tortured before being killed at Choeung Ek, the city’s most prominent Killing Fields, fifteen kilometres outside the city. The Vietnamese, facing little military resistance, liberated Phnom Penh in January 1979. Following the Vietnamese occupation and the ensuing civil war, Phnom Penh remained in a dangerous and tragic limbo for more than a decade.

A painful rebirth

In the 1980s and 1990s, some former inhabitants as well as thousands of rural squatters in search of opportunity slowly reoccupied the city. But restoration was slow and around the turn of the millennium, many roads in the centre remained unpaved and barely lit. Armed robbery was as common as public services were non-existent. The city’s fortunes began to change in 1992, when Untac (the United Nations Transitional Authority) rolled into town and organised elections. Thousands of well-paid foreign soldiers and consultants created a new economy almost overnight, and bars, shops, brothels and hotels sprung up all over the city centre, providing the basis for the vast NGO-orientated infrastructure Phnom Penh is graced with today. Cambodian politics remained turbulent and following the 1993 elections and the UN’s departure, civil strife continued for some years, including intense fighting in the capital in 1997. Luckily, though, Phnom Penh has managed to retain a great deal of its glorious past, partly because the city was denied ‘development’ for so many years, and it will take some time before all the traces of its golden era have been removed. For now, Phnom Penh retains an easy 20th century charm – a capital that is still some way from becoming one of today’s Asian mega-cities. If only Lee Kuan Yu had paid proper attention.

Cambodia: A Journey Through The Land Of The Khmer, by Tom Vater (copy) and Kraig Lieb (pix) is available now at Monument Books for $35