Ian Woodford, a throwback to the country’s bygone Untac era and a tall, wiry character whose colourful Australian language and endless Cambodian anecdotes were a cherished and longstanding part of Phnom Penh expatriate lore, died on May 23 in Sydney. He was 56.

The cause was complications following lung surgery, his daughter Maxine said.

In those heady Untac days, Phnom Penh was a town full of soldiers and mercenaries, chancers and grifters. Few would last; even fewer were worthy of keeping.

“I will always remember Snow as a fearless defender and supporter of anyone he considered a friend, which to my humble pleasure included me,” said Phnom Penh Post founder and fellow long-timer Michael Hayes, using the nickname by which Woodford was known. “Countless times in the last 20 years, when I’d see him somewhere along the riverfront or at his glorious, deliciously kitted-out oasis across the river, he would make a specific point of telling me that, first, he loved the Post and the stories we were running; second, that he admired what I was trying to do; and, third, that if I ever needed any help, no matter what kind or at whatever time of day or night, all I had to do was give him a call and he would be there – physically, in person, ready to do what was needed. And the thing with Snow that meant the most is that I knew what he was saying was a personal unwritten law among mates, not just some kind words thrown out in passing, but an eye-to-eye oath among kindred spirits.”

Born October 30, 1957, in Bega, New South Wales, Woodford grew up in Dundas, a suburb of Sydney. He moved to Phnom Penh in 1993, just as the United Nations Transitional Authority of Cambodia was winding down its $1.6 billion machine. Woodford found work as a contractor with a cowboy Australian outfit. His first job included working with Khmer Rouge soldiers in Ratanakiri, ensuring ‘safe passage’ of UN vehicles out of the province.

“It was just me and an American named Bob, who left after two trips,” Woodford told friend and fellow Australian Bronwyn Sloan in a 2008 interview. “It took five trips, 150 kilometres each way, at nine hours per trip, to deliver all the vehicles. Along the way, we regularly collected groups of Khmer Rouge, who would make us stop on secluded roads to drink homemade wine from plastic bags around the vehicles. Then they’d suddenly disappear into the jungle and we’d be off again. At Kratie, the UN helicopters would pick me up and take me back to Stung Treng to begin another convoy, but one night I got stuck in a Kratie hotel room with 31 Khmer Rouge soldiers because the choppers couldn’t land. I thought I was finished. When I returned, the UN soldiers looked at me very differently: they respected me… but they thought I was crazy.”

The UN left soon after, but Woodford stayed behind, enamoured with the Kingdom and its edgy, post-war disorder. He began teaching English at The American School, where he stayed for more than a decade. His reputation grew with each major news event, which, when at all possible, Woodford preferred to witness from the most dangerous vantage point available.

During the violent clashes of July 1997, Woodford and a few crazy-brave friends grabbed cold ones and roamed the streets searching for the ‘bang bang’. In the aftermath of national elections a year later, Woodford, cold beer in hand, ducked around trees and dived behind corners following the sounds of machine-gun-fire down Street 63.

“Whether it was about Islamic militants who were scouting the capital a decade ago or the constant political machinations of his commune, Snow’s knowledge and advice was as sound as it was welcomed, more so after a hot day with a cold beer,” said Luke Hunt, another long-time friend. “But what always struck me was the diversity in his character, a doting father who dabbled in the arts and ran one of the most celebrated bars in the country. Fleet footed, Snow also had the hands of a prize fighter, the soul of an artist and the heart of a lion: qualities which are often in short supply in this country.”

It was in 1997 Woodford rediscovered a childhood love of art, and in the small apartment he shared with his girlfriend Annie, he began drawing then painting in earnest. His only child, a daughter named Maxine, was born soon after in December 1999. Fatherhood turned Woodford from a fast-living thrill-seeker into a proud papa. As Maxine began to walk then run, the two left the capital for a quieter place on the Chroy Changvar peninsula, where Maxine could learn the joys of grass and trees.

In 2001, Woodford landed a small part in Matt Dillon’s City Of Ghosts. He played a drunk and belligerent foreigner in a red-light brothel. Roland Neveu, the film’s official photographer, captured the scene and a copy of the image still hangs in Cantina, one of Woodford’s regular watering holes. As Maxine reached school age, Woodford began to think better of Cambodia and in 2004 the pair returned to Australia, but neither one of them liked it much and they were back after only a few weeks.

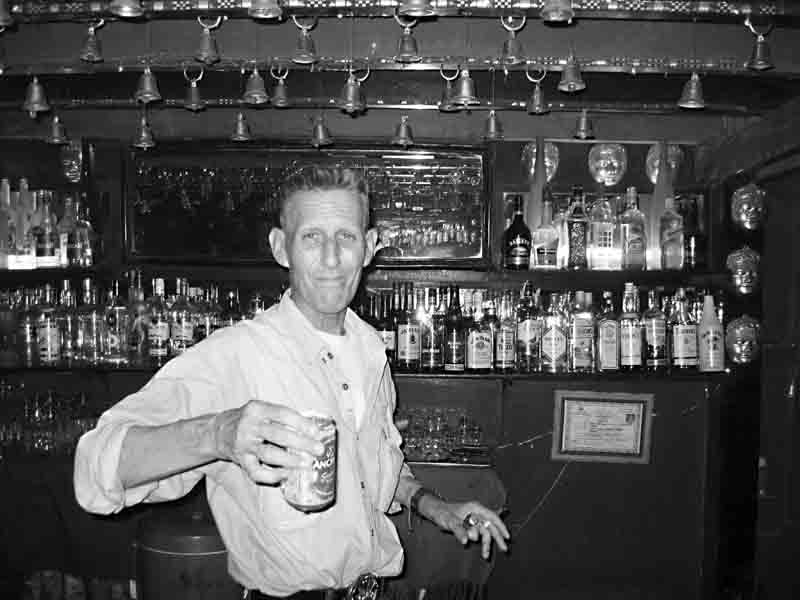

In late 2005 Woodford opened Maxine’s Bar in a large, blue wooden house on the east side of the Tonle Sap River. It was as casual and quirky as he was. A table made from decommissioned AK-47s occupied centre room for a while. A thousand bells hung from the ceiling and when the wind blew they made beautiful music. More than one person thought it the best bar in Southeast Asia, maybe even the world. Dengue Fever played one of their earliest Cambodian shows there. National Geographic and celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain both used it for production settings.

Woodford worked Maxine’s at night and followed his passion of painting during the daytime. He worked in an aboriginal style of dot painting and filled the bar with his art: first portraits, then vases, masks and tables. Before long his art was fetching impressive sums and he finally gave up the day job. “I’ve always been decorative,” he told Sloan in 2008. “Even at school I always used to draw, but art was extra-curricular so I used to cop a lot of stick from the lads, teasing me and calling me a girl for wanting to paint. A lot of stick. But I have always loved things to be bright and vibrant and beautiful in any home I’ve ever had. This elephant lights up the room, doesn’t it?”

Just as things were starting to take off, a health crisis threw Woodford for a spinner. “I was sold some fake medicine [in 2007] by a clinic and before I knew it, it was touch and go whether I would make it or not. It took out my liver and part of my lungs.” He tried to continue painting, but the acrylic fumes were just too damaging to his lungs. In 2011 authorities told him he had to close the bar; the land was needed for drainage and road projects. Then the lung problems came roaring back and he and Maxine made a permanent move to Sydney.

Woodford endured two more major thoracic surgeries, he told friends over beers during what would be his final time in Phnom Penh late last year. Each time under the knife could have been his last, he said. They cut him open from the hip to the armpit. Twice. And he made it through both times, if just barely. Now he was back, if not 100%, at least well enough for some rest and relaxation. “The doctors cut me loose. They told me: ‘Take a vacation, mate. After all you’ve been through you deserve it.’”

“Excellent,” Snow replied. “I know right where I’m facking going, too.”

A local memorial service is planned for 9am Sunday June 1 at Wat Saravan.

(Photo: Bill Irwin)