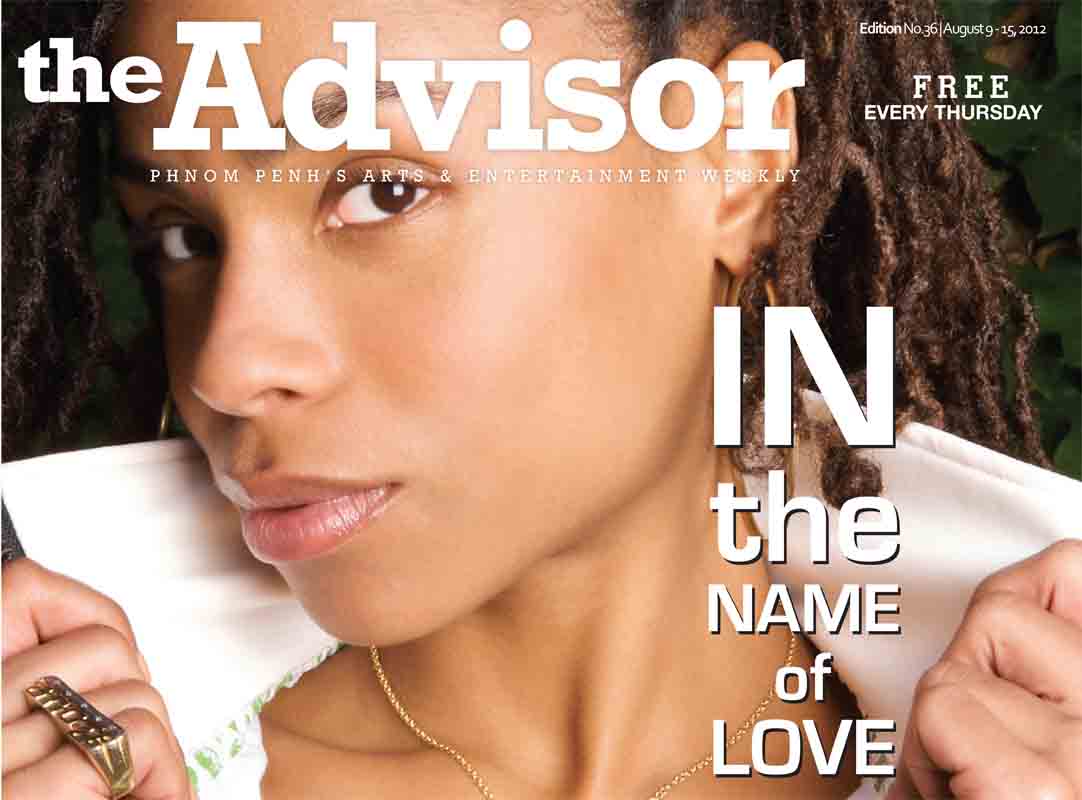

She describes herself as a ‘one-woman worldwide wreckin’ machine’, was instrumental in the launch of MTV Base Africa, and is the only female ever to be nominated for a MOBO (Music of Black Origin) award. DJ Sarah Love, spinning at Pontoon later this month, was christened the UK’s First Lady of Hip Hop for a reason – and she’s on a zealous mission to bring the genre to some of the most remote corners of the Earth. The Advisor caught up with her between rock climbing expeditions in Thailand to talk DNA, spinning the wheels of steel with Grandmaster Flash, and the ongoing battle to keep hip hop culture alive and kickin’ it.

You describe yourself as a ‘genetic musician’.

Yeah, my mum’s South African and my dad is British. They’re both jazz musicians , and my mum’s an African musician too, so quite a mixture of sounds. My dad’s really into bebop: his main instrument is double bass, but he also plays trumpet and piano, and my mother’s a singer.

Why did you opt for electronic music?

I’ve been interested in music since a very young age. I’ve played piano, drums. Music’s always been there, and my parents’ record collection was always there. They were very much into soulful music, funk, dope party-rockin’ kinda tunes. My older sisters introduced me to hip hop. I had this nerdy fascination with music. I didn’t just want to be on the sidelines, I wanted to be involved. I wanted to find out how those sounds were made, to know what was going on. My own curiosity pushed me into investigating hip hop. What is this DJ thing? What are they doing? How is that happening? I had a boyfriend who was also a DJ, and I asked him to show me some things on the turn table but he refused. I was, like, ‘Cool. Fine.’ I thought, ‘Good. I’m happy to do it myself anyway.’ My parents taught me to be very independent. I watched DJs I thought were really good, and tried to memorise what they were doing. I’d go home and practice, see if I could recreate what I’d seen. It’s a ‘monkey see, monkey do’ sort of thing. Making mistakes is a great learning curve.

And you’re a graduate of one of the UK’s finest music schools.

I went to one of the pioneering schools for popular music, Salford University in Manchester, and did a popular music and recording degree. Salford was the first place in the UK that did a non-traditional, popular music recording and production-style degree.

You’ve worked with some of the greats, including Grandmaster Flash, who was here a few months ago.

He’s a real grand master in the game, a bona fide legend. It’s only a privilege and an honour to be able to rub shoulders with someone as accomplished as that, really, isn’t it? And DJ Muggs from Cypress Hill, he was just a laid-back, cool Cali cat with a cool Cali vibe. Chilled dude. But it’s always interesting to encounter all sorts of creative types at different levels in their careers and see how they handle that.

How has hip hop changed since you first took to the decks?

In the UK, there’s lots of electronic music that people are rapping on top of, but I differentiate between that and hip hop, which has a long history – three decades plus, almost as long as hip hop has been around in America. It’s a dedicated crowd. We’re all musical connoisseurs. That’s why hip hoppers are able to spin off and create other movements. Anything that’s dope has to come through the UK at some point. It’s like a melting pot for all the freshest stuff in the world. London is always a place to keep your eyes on, whether it’s live music, electronic, or hip hop. We’re always going to have hip hop aficionados to keep the bloodline going.

We’re a bit of a melting pot here too, with returnees from France and the US. Hip hop has a huge following.

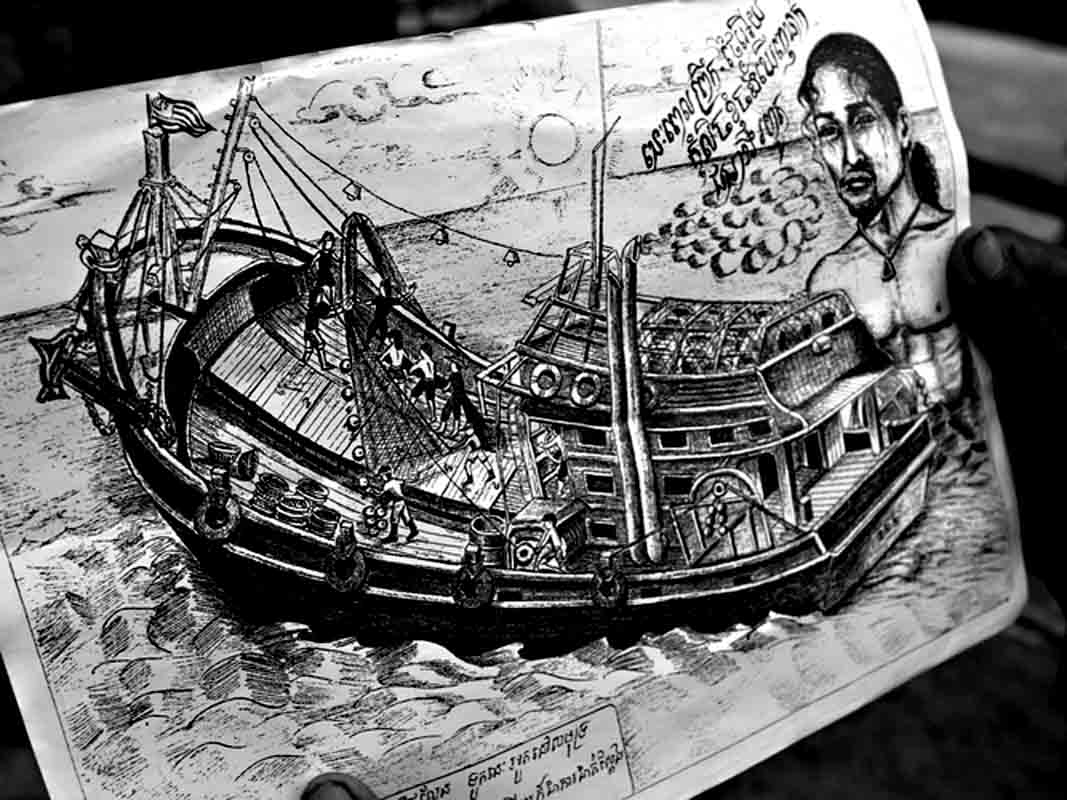

It’s fascinating to touchdown in any part of the world and be playing hip hop. It’s incredible to spend 12 hours on a plane and people know the music, and there’s a history of hip hop there. To encounter b boys, and graffiti, it’s just crazy. I feel it’s my responsibility to fly the flag for hip hop responsibly and correctly, to spread the word and keep our culture vibrant and alive.

There are so many DJs who’ve been around longer than me, but have sold out because they don’t feel confident. I just want to do what I feel passionate about. It’s not all about just chasing cheques. I want to do something that has meaning to me, so it’s an honour for me to be able to reach somewhere like Phnom Penh and spin for you guys, bring hip hop correct to the people.

With the launch of MTV Base Africa, you seem to be growing into an ambassadorial role.

I’d been an MTV DJ so when they asked me to be an ambassador for the launch, I came through to Nairobi in Kenya and had a phenomenal time. It was dope to be in the motherland, you know, and doing my thing there. Then I went through to DJ in Tanzania, and they have a dope, dope hip hop history there. I did a show with Fid Q, in Dar Es Salaam – a big outdoor party with 3,000 kids there and they’re all rapping the lyrics to his song; just beautiful. These are the messages and stories that I want to spread when I go back home, because people think we’re facing all these challenges in hip hop. A lot of people in the States are quite disheartened with hip hop, hence they become sell-outs. They need to know. You know what? There’s stuff going off in Tanzania; there’s stuff going off in Cambodia. There are things going off in Australia. Hip hop around the world is bigger than your back garden.

So it stands for something?

Most definitely, hip hop has a very strong meaning and this is the message that needs to be clearer. There’s hip hop, and there’s rap. Rap music is songs that just have rapping on them; hip hop music is a whole culture, nearly four decades deep, that embodies dancing; it’s all about creativity, expression, community, and being funky fresh. It’s something that involves speaking in rhyme with flow and beat. It’s something also that embodies respect for heritage: you have to look at what has gone before you, do your research, and then cultivate that and bring it all together in something new. Hip hop is a culture that’s all about the people. It was originally for disenfranchised people who had no other outlet, a way of channelling ourselves in a positive way. People who were left behind by the government: ‘Oh, right. No one’s taking care of us? Let’s take care of ourselves.’ That’s what hip hop is really about, and it’s only in recent years that it’s become this corporatised thing and certain entities see it as a way to manipulate youths to make money out of them. It’s a shame that certain people from our community have got sucked into that and are now sucking the devil’s cock.

Who should we be looking up to?

Marvin Gaye said an artist, if they’re a true artist, is only interested in one thing and that’s to move the minds of men. So for me, people like Shortcut, who I’m going to see next week; people like Shortee Blitz, Taskforce, and Rodney P of London Possee from the UK; I have so much admiration for them.

And what’s on your playlist right now?

I listen to everything: rock, soul, classical. My favourite kind of music is good music. There are only two types of music in the world: good music and bad music. I’m not someone who goes ‘I only listen to hip hop and I have no ears for anything else.’ But hip hop-wise, there’s an artist called Willie Evans Jr – he’s on a great label in the States called High Water Music, and they’re really flying the flag for great independent music. There’s an artist called Sonnyjim on Eat Good Records who is really killing it – a very dope artist from the UK. Definitely worth checking out.

Take us back to the early days of Kung Fu: what was it like being on the front line of one of London’s most legendary club nights?

I remember, every night at the time, feeling that this was something classic. I just wanted to absorb every moment of what was going on. I knew we were going to be looking back at this as something classic – and I was right. It was incredible. I was in Melbourne, Australia last month and I’d just walked into a bar and this guy was, like, ‘You’re Sarah Love! From Kung Fu! You don’t understand – the DVD from Kung Fu, how much that means to us out here! We watch it religiously!’ You had to be there every month. Every month we had a queue going round the block. You didn’t want to miss out and we always put on the best party in town. It was so exciting for me to play. I just wanted to kill it. We had the illest DJs in London playing, and it really pushed me to get my chops up because I didn’t want to look silly next to anyone else. It was an honour for me to be a resident and to see what it escalated into.

Do you ever have moments when it suddenly hits you that you’re now this huge DJ?

I’m always thinking of my next target, so I don’t reminisce too much. When you sit back and start going, ‘I’ve made it. Look how amazing I am,’ that’s when you stop challenging yourself. I’ve not reached that stage yet, and then there’s always someone bigger than you round the corner, isn’t there?

And even if there isn’t, the Gods of Smug are listening and will smite thee…

[laughs] Exactly!

So what’s next?

I’ve spent the past 12 years pushing myself like crazy, at the expense of everything else in my life, and it’s easy to do that when you love what you’re doing. I’m trying to pay attention to other areas of my life that I’ve been neglecting, and I’ve got some interesting projects back in the UK, but I don’t like talking about things until they’re happening. I’m paranoid about jinxing things…

WHO: DJ Sarah Love (MTV Bass and BBC Radio 1Xtra)

WHAT: The UK’s first lady of hip hop

WHERE: Pontoon, St. 172

WHEN: 11pm August 17

WHY: She’s funky fresh