Immortalised by Rolling Stone magazine as one of the 50 moments that forever changed the history of rock music, the famed Woodstock Festival of 1969 was far more than just three days of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll.

On the front page of a special report on the so-called ‘Aquarian Exposition’ by Rolling Stone’s editors, the photographer – shooting from over the shoulder of a young, shaggy haired Carlos Santana – captured an apparently endless ocean of human flesh, stretching from the front of the stage to the vanishing point of the festival’s sprawling 600-acre site in Bethel, New York.

High on marijuana and dancing naked in the mud, half a million devotees of hippie counter-culture flooded dairy farmer Max Yasgur’s fields between August 15 and 18. During ‘three days of peace and music’, 32 acts – including Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead, and Janis Joplin – took the stage in one of the most pivotal moments in music history.

“Woodstock was a spark of beauty” where half a million kids “saw that they were part of a greater organism,” Joni Mitchell later said. Hers was a sentiment shared by Michael Lang, one of the organisers: “That’s what means the most to me – the connection to one another felt by all of us who worked on the festival, all those who came to it, and the millions who couldn’t be there but were touched by it.”

Among the festival’s audience was one of the owners of Indochina’s longest running rock ‘n’ roll bar, which this month will host its very own three-day rock-fest in tribute not only to the original ethos of Woodstock but also to emerging local talent. Then just 13 years old, he is today known as ‘Big Mike’ and is one of the chief architects of Sharky’s transformation from arms dealers’ den to legitimate showcase for new rock bands, both Khmer and barang.

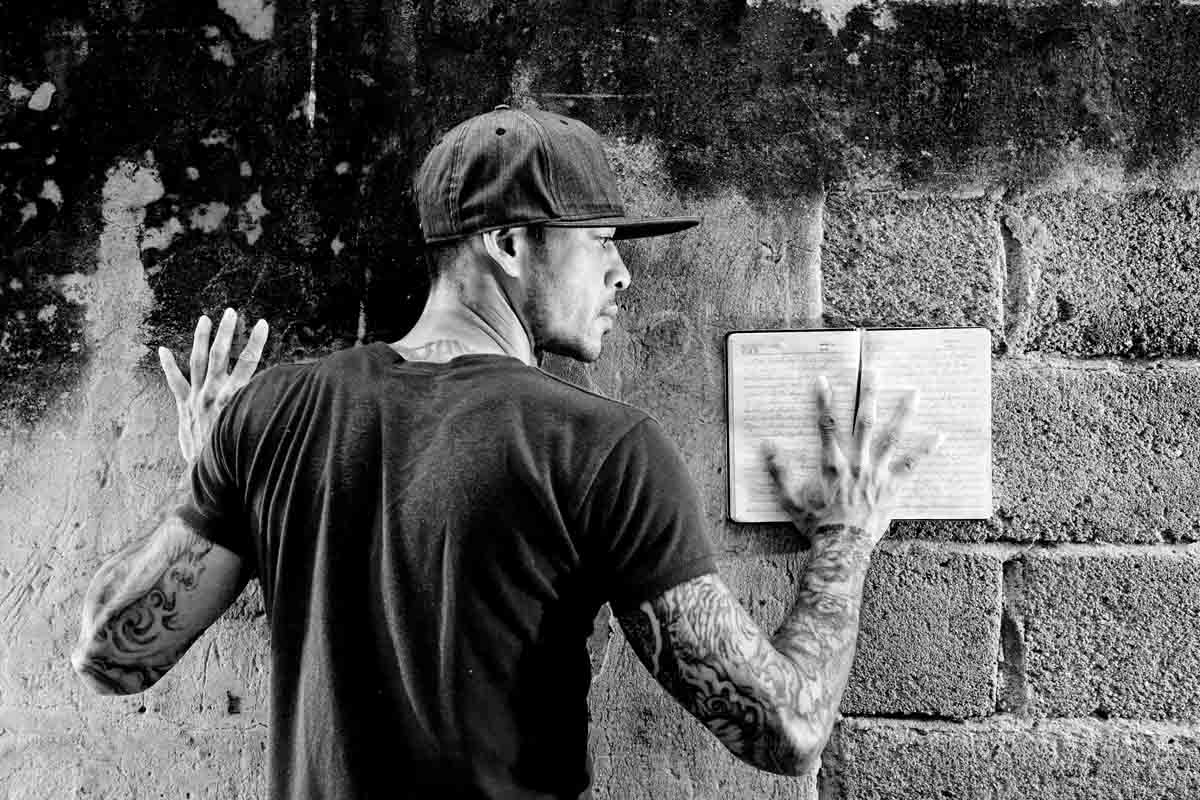

“There’s a photograph of me at Woodstock with Jimi Hendrix,” says Shanghai-born Mike, balancing his large frame on a tiny stool in the bar’s cluttered rehearsal space, known as The Shark Cage. A bold handwritten notice taped to the outside of the glass door serves as a warning to would-be invaders: ‘BAND ONLY.’ Beneath the capital letters, in Biro chicken-scratch, someone has scrawled the words ‘and beautiful and available groupies’.

“I had no idea it even existed. I found it about four or five years ago when I went back to Woodstock. I went into a music store and asked the proprietor if he had any posters. He said: ‘Only one, in the front window, of Jimi Hendrix.’ I said: ‘Perfect!’ Hendrix was my hero. So I went outside and I’m looking at this poster and it’s Jimi Hendrix on stage at Woodstock – he was one of the last acts. I was really young, 13 I think. I’d gone with a few friends, was there for four days and stayed up way past my bedtime. I didn’t care about the mud. It was just on my mind to get to the front of the stage. I had to see Jimi Hendrix.

“So I’m looking at this photograph of Hendrix, with his drummer Noel Redding, and I thought: ‘That’s it! My God, I was there…’ And then all of a sudden, in the foreground of the photo, I see myself – wearing dark sunglasses that I still have and a hat that I lost – giving two peace signs. I fell in love with rock music at Woodstock.”

It was to prove a lasting romance. By the time the nascent punk movement of the 1970s was gaining momentum, Mike was old enough to start work – first as a bus boy, later as a music manager – at what would become New York City’s most legendary rock clubs. One of the first was Dr Generosity’s, a saloon at 73rd and 2nd on the East Side, where he met a young Keith Richards. “This was a starting place for rock stars,” says Mike, jet black hair cascading down to his shoulders, both wrists heavy with studded leather trinkets.

But it was at Max’s Kansas City, on the corner of Park Avenue and 17th Street, that Mike jabbed a needle into rock music’s main artery. The downstairs restaurant, where Debbie Harry once waited tables, was a hub for poets, painters, fashionistas and photographers; the seedy backroom was immortalised in Lou Reed’s Walk on the Wild Side. Upstairs was converted into a performance space where Patti Smith and Television played. “That’s when I began to know all the bands and I became a Hell’s Angel, because all the Angels came in on a Friday and Saturday night. Andy Warhol was afraid of them, so they had to go upstairs – and upstairs is where all the music was, where all the bands came.

“That’s where Iggy Pop and the Stooges got started, and The New York Dolls, David Bowie, Blondie before she was Blondie… It was fantastic to see all these bands. It was the end of plastic rock and going into glam rock. I saw Bowie for the first time, cross-dressing. He was wearing all gold, totally all gold, and sparkles, with platform heels. I looked at him and said: ‘What have I got myself into?’ Then The New York Dolls came in and they were all cross-dressers too. But their music was fantastic. It was music I’d never heard before.”

More than a decade later, following tussles with both ends of the legal spectrum – the Hell’s Angels and the US authorities – Mike landed, via a stint in Bangkok, in Cambodia, a country still in the throes of civil war. “By 1996, Sharky’s was full of arms dealers and soldiers. That was the nature of our clientele – mainly military.

“It was very, very rough. We had a lot of drive-by shootings. We had a locker downstairs with about 12 AK47s and M16s in it. We had six rocket-propelled grenade launchers in the office, 12 RPGs, a box of 96 hand grenades, about eight to ten handguns, and everyone had to learn how to use them. It was tough. The change came right after 2000. I was walking down by the riverfront and I remember very distinctly that I saw a young, well-dressed European woman walking in high heels. I turned to my business partner and said: ‘It’s over.’ He said: ‘What’s over?’ I said: ‘The military. It’s over.’

“Suddenly, I remembered my past, with the Ramones, CBGBs, the Dead Kennedys, the Misfits, and all those bands. Having been friendly with them and having worked in that bar environment, at world famous punk and glam clubs, it hit me in the head. I said: ‘This place will be converted into a music club.’ So here we are: it’s 2012 and we’re now three years into the change.”

Sharky’s is budgeting another three years for that change to take full effect, hinging in part on the relaxation of local laws to allow bands to play deep into the night, but – like New York’s famous cradles of punk rock – the club is already spawning its own nascent scene. And the annual crescendo is Penhstock, when more than 30 bands will take the stage over three days.

“Penhstock is about my memories of Woodstock and my contribution to the alternative music scene here in Cambodia. The first year, we had five bands and we realised we needed to get more, so I begged the musicians to find splinters – get another musician from over here, and another musician from over there. We were able to turn five bands into eight bands within the space of three days. Last year, we were more fortunate and had 20, which began to allow us to turn this place into a showcase for young Khmer bands and alternative music – indie, rock and heavy metal. That’s what we did in New York – at Max’s, at CBGB’s, at Dr G’s – and some of those bands, like The New York Dolls, turned out to be huge.”

Among the local bands already making ample soundwaves are Cartoon Emo, who played at last year’s Penhstock and are now perhaps Cambodia’s most famous Khmer rock/heavy metal group. They released their first album of original music, Shadow, on Svang Dara Entertainment in 2010 in what Mike hopes will prove a precedent-setter.

“We’re also fortunate enough to showcase other Khmer bands such as Anti-Fate and Millennium. All of these are going to be headlining at Penhstock. The bands with the largest following will be the last on each night; the bands we feel will be very difficult acts to follow. On the Friday night, Herding Cats will be our last band. Their vocalist has what it takes to become an overwhelming personality on stage. Someone who’s out in front, right in your face, not ashamed of it, and if you don’t like it, go fuck off. That’s the kind of music I grew up with and I love it.

“Saturday’s last act is Sliten6, which we believe is the next Cartoon Emo. Last time they played here, they all took their shirts off and the crowd went crazy. They’re a very difficult act to follow. On Sunday night, to show our respect, we’re giving the show over to the longest running rock ‘n’ roll band here, Bum n Draze. They’re impossible to follow; great entertainers.

“Next year, we’re hoping to have 40 to 50 bands, possibly an outdoor venue. We’ll see where it goes, but this bar is going to be a stage for new Khmer and barang talent. We’re going to clean up the place a bit, but it has a certain grungy charm and that’s how it’s going to stay.”

WHO: 30 of the best local rock bands

WHAT: Penhstock III

WHERE: Sharky Bar, St. 130

WHEN: May 11 to 13

WHY: Southeast Asian rock music history in the making